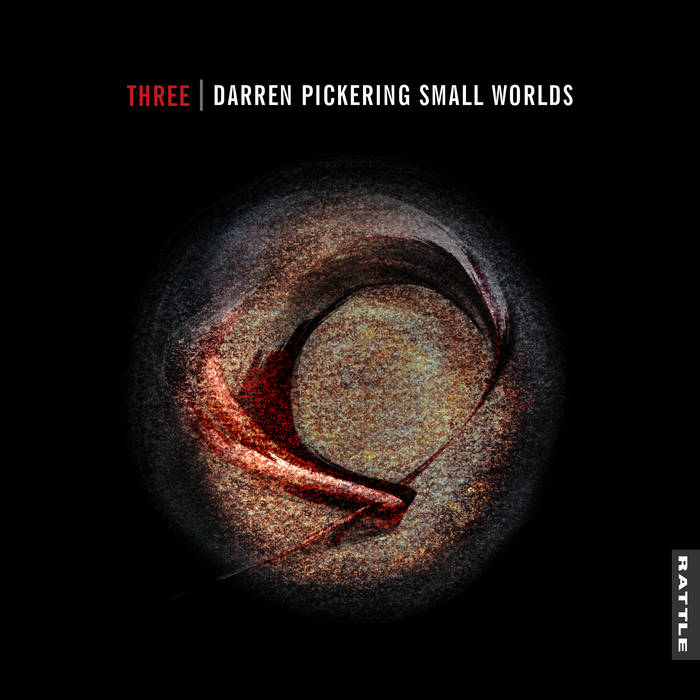

Three (Darren Pickering Small Worlds)

Darren Pickering’s third Small Worlds album, ‘Three’, is a welcome addition to the earlier volumes. While it follows the successful formula developed in volumes one and two, it sounds fresh and endlessly explorative. Throughout the album, snaking lines float, dreamlike, over repeating patterns and carefully layered grooves. Out of this comes the quartet’s cinematic sound. Jazz and cinema are twin arts as they evolved together, often feeding from the same well of resonance. Because of that focus on imagery, you can get inside the sound and experience it on many sensory levels. Listening to this is like watching a great movie – in a theatre – on a rainy day.

This is a superb quartet; unsurprisingly, after two previous albums, they are hyperaware of interplay. This is particularly important in an album like this, as the soundscape is so open. The liner notes indicate they have equal input into the artistic direction, which makes sense; the democratised approach is evident. This is jazz for our times, probing but gentle and unashamedly open to influences.

As with the first two albums, the tune times vary in length, enhancing the listening experience. Nothing is extended beyond its natural endpoint. Like the written word, contrasts like this punctuate the ebb and flow. There are small, meaningful solos, but they are skillfully interwoven into through-composed pieces.

Immediately noticeable is Pickering’s touch, and the underlying digital or analogue wizardry never overwhelms. While often understated, his pianism shines throughout. Pickering is a thoughtful composer and writes to his strengths.

Guitarist Heather Webb is pitch-perfect throughout, her sound is so distinctive, with lines that fold effortlessly into the mix. Her avoidance of anything showy or unnecessarily loud marks her as a mature player. I wish more guitarists understood this. The same can be said for the drummer Jono Blackie and bass player Pete Fleming. Both blend into the mix, thus enhancing the music, making the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

The rainy day groove is particularly evident in ‘Soft Life’. With Webb running her silken lines over Pickering’s synthesised arpeggiation, and the measured, but perfectly placed, beats like slow-dancing footsteps. And the faster-paced ‘Tauhou Waltz’ has a similar vibe. The album maintains this flow, touching on various moods, but always speaking in a calm voice. The album can be accessed from Rattle Records or Bandcamp. https://darrenpickeringsmallworlds.bandcamp.com/album/three

Under Ocean (Chris Cody/Charlie Tait)

I have long been an enthusiast for Chris Cody’s work, and his two latest releases, each different from what went before, enhance an already impressive discography. Cody has a gift for examining cultural intersections. He gathers events and places, past and present and puts them under a musical microscope, always leaving us with a sense of what it means to be human.

‘Under Ocean’ is a fresh approach with electronic enhancements and a duo format. The album traverses mental and physical landscapes in unexpected ways and, in doing so, expands not only Cody’s repertoire but the boundaries of improvised ambient-style music. The album is co-led by Charlie Tait, a multi-instrumentalist, sound designer and engineer. Tait is no stranger to sonic creations like this, and the resultant cross-fertilisation of jazz, classical, and ambient electronic music is fascinating.

There is an increasing imperative for improvising musicians to create music like this as a reaction to the realities of our overly commercialised modern life, to examine our interior landscapes or the natural world. It also reacts to the ugliness that intrudes on the quieter spaces. They combine new and old musical technologies to good effect, as evidenced in the atmospheric opening track, ‘Salt’, which contrasts with ‘Rumble’s’ free playing and the melancholic ‘Lost World’, bringing different moods together as a satisfying whole.

Mountain to Sea (Chris Cody)

Landscape itself is a featured guest artist on most of Cody’s albums, as his writing always conveys a strong sense of place. I am not referring to specific geographic locations, although they sometimes feature, but to something deeper – cerebral. Cody has a gift for inviting introspection, and as we listen, we examine our relationship to the landscapes and regions he evokes. It is the first thing you become aware of when listening to his albums; ‘Mountain to Sea’ is no exception.

His compositions and arrangements impress here, but his thoughtful playing is also notable. His lines and voicings convey an instinctive lyricism, an organic sound that has always defined him. The tunes contain nostalgic echoes, but speak of hope too, a heart-on-the-sleeve musical humanism. And, as in previous albums, he conveys more with less. There is ample room for his bandmates to shine, and they do. The care and loving attention each one brings to the project is evident. It is no wonder the unit sounds so good when you consider the musicians, a mix of veterans and younger players, but all exemplary: bass player Lloyd Swanton (a member of The Necks who appeared in Auckland recently) and who appeared on an earlier album ‘The Outsider’ (reviewed recently on this blog), and Sandy Evans, an acclaimed saxophonist on the Australian jazz scene, and lastly Tess Overmyer, a gifted young Australian alto saxophonist, presently based in New York.

‘Mountains’, a ballad, opens with Ellingtonian chords that speak of grandeur, followed by two beautiful solos, lifted to further heights by bass lines that never intrude, but soar like a raptor. Similarly, ‘Quiet’ reminds me of Evan Parker’s opening on Kenny Wheeler’s ‘Sea Lady’ (Music for Large and Small Ensembles). Ripples, bird calls, lead into an elegiac anthem for the natural world, a place not separate from humankind, with alto, tenor and soprano perfectly balanced, drawing from the same musical well. This is also evident in ‘Dream’.

As with previous albums, Cody’s daughter Maya has created marvellous cover art.

Both albums are available on Bandcamp at https://chriscody.bandcamp.com/

JazzLocal32.com was rated as one of the 50 best Jazz Blogs in the world by Feedspot. The author is a professional member of the Jazz Journalists Association, a Judge in the 7VJC International Jazz Competition, and a poet & writer. Some of these posts appear on other sites with the author’s permission.