Earlier this month ‘Blue Note in My Suitcase’ was released by B3 Master Michel Bénébig. It is his sixth album and his first with a Jazz orchestra. The album hits the groove spot immediately, and as you listen you realise what a perfect pairing Bénébig’s B3 and the Le Grande B3 Orchestra is, aided convincingly by Lachlan Davidson’s lovely arrangements. The charts are well constructed, giving free rein to the soloists and never overwhelming the organ. Davidson is a respected Australian arranger, teacher, band leader and multi-instrumentalist and his influence is strongly felt here.

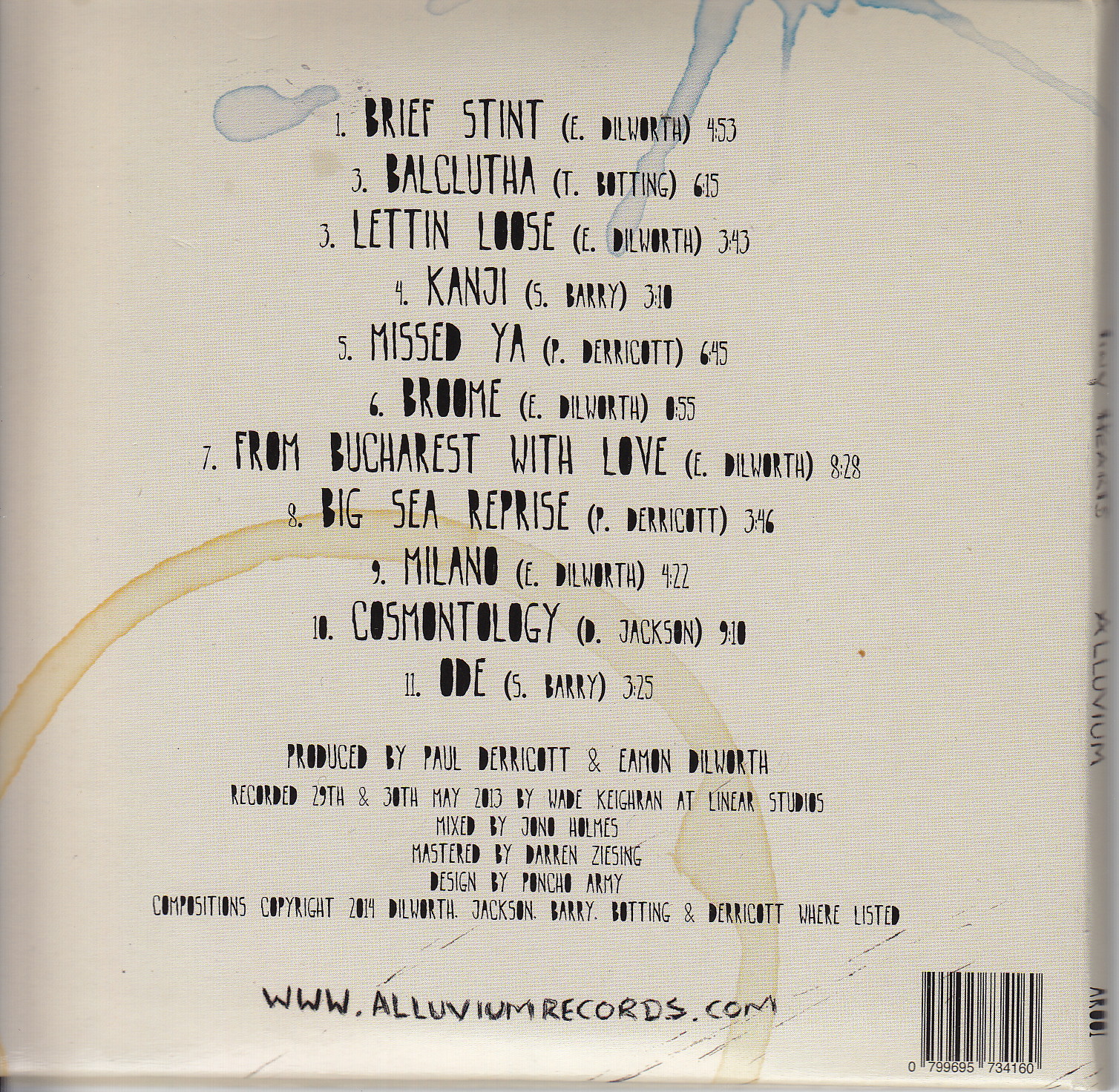

It is always a pleasure to hear Bénébig’s in-the-pocket playing but with an orchestra like this charging the atmosphere, he digs deeper than ever into the groove. The ten tunes on the album are excellent groove vehicles, all written by Bénébig, with Davidson credited as co-composer on ‘Try To Explain’. I have always appreciated Bénébig’s writing but he has excelled himself here.

The opener ‘Alenka’s Mood’ is warm and funky, immediately infecting you with its slinky rhythm. It offers up a promise which is fulfilled throughout. As you work through the tunes you are drawn back to the days when infectious danceable music like this was loaded onto jukeboxes and played in steamy groove joints pulsating with dancers. The music brings a smile to your face and fills you with joy and, like his earlier ‘Shuffle’ album, you will reach for it repeatedly. Joining him is Bénébig’s daughter Lucia who is responsible for designing the album cover and creating animation for a promotional YouTube clip. I have posted the YouTube cut ‘Black Cat’ from the album.

A time-honoured B3 big band tradition is followed here, featuring 13 horns which lends considerable heft to the rhythm section. It would be easy to drown out soloists and to eclipse the organ with a behemoth like this but the soloists get plenty of room to shine, and shine they do. The album is available now on Spotify and a vinyl edition is on the way for audiophiles.

Mick Fraser (trumpet 1), Shane Gillard (trumpet 2), Gianni Mariucci (trumpet 3), Rob Planck (trumpet 4), Roger Schmidl (trombone 1), Ben Gillespie (trombone 2), Jessica Jacobs (trombone 3), Adrian Sherriff (bass trombone), Lachlan Davidson (alto sax 1/flute 1/sop sax), Rob Simone (alto sax 2/flute 2), Anton Delecca (tenor Sax 1/clarinet 2), Paul Cornelius (tenor sax 2/clarinet 1), Stuart Byrne (baritone sax/bass clarinet), Jack Pantazis (guitar), Gideon Marcus (drums), Michel Bénébig (A105 Hammond organ Leslie 147), Phil Noy (recording engineer), Lachlan Carrick (mastering Engineer), Lucia Bénébig (front cover art)

~Random Delights~

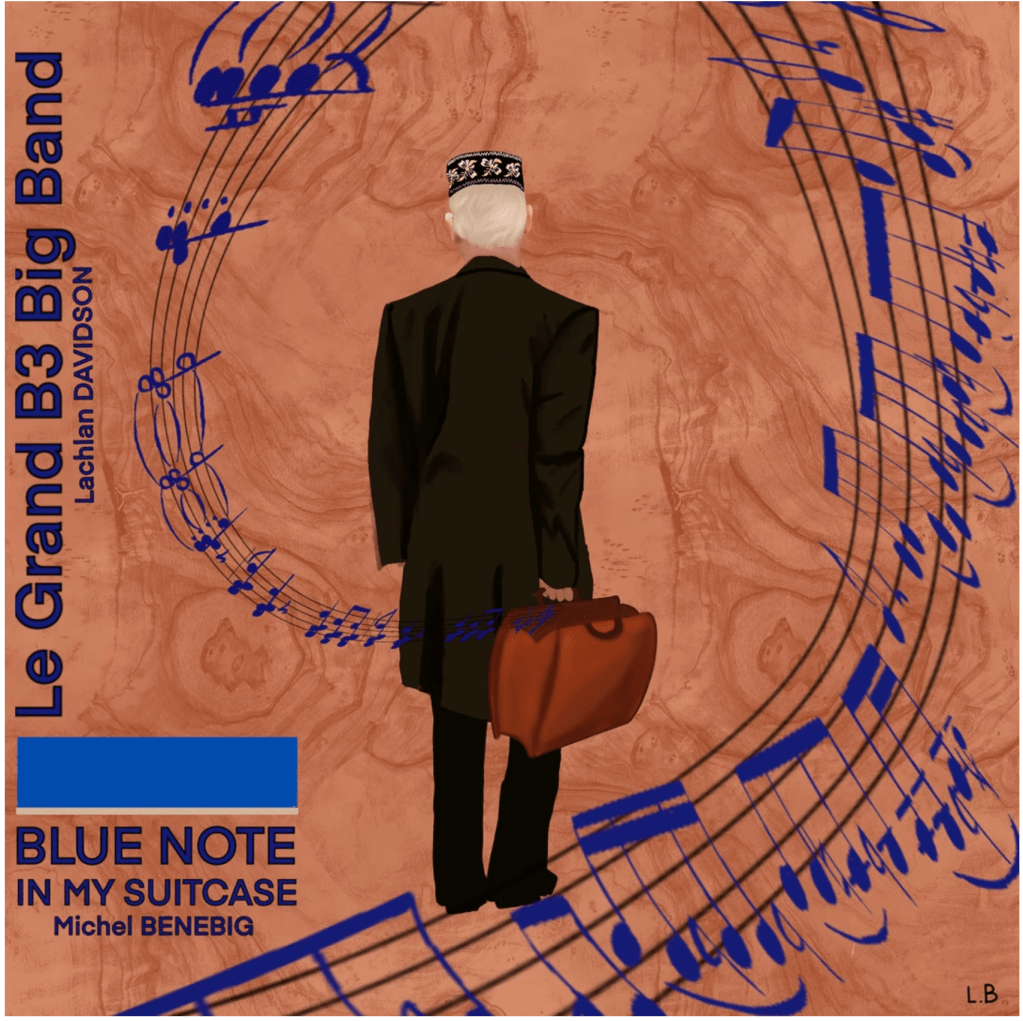

Sambandha: Heartcore For Nepal

Recently, I received a press release from colleague Arlette Hovinga. The project outlined was the vision of Mikaela Bokova, the manager of Kurt Rosenwinkel’s independent music label, Heartcore Records. The object was to raise money for disadvantaged children in Nepal, and on board for this recording are an impressive list of jazz and world music luminaries: John McLaughlin, Christian McBride, Terri Lyne Carrington, Gerald Clayton, Kit Downes, Anmol Mahara and Dinesh Pun. Sambandha was written by combining two traditional Nepalese folk tunes, and it’s performed by the 20-piece children’s choir Bokova organised while running a music workshop at Mangala School, Babiyachaur, Nepal.

The revenue from the release will go towards buying the children’s musical instruments. In your browser or here, click on heartcore-records.com then once opened, locate Sabandha and purchase your download (5 Euros). It can also be purchased in Bandcamp. Please pass on the word and enjoy. I play this often. You will also find a delightful video on YouTube on the making of this by typing Heartcore for Nepal Sambandha. There is a deficit of joy in today’s world, but giving to those in the greatest need is a sure way to top up the supply.

Skilaa: Tiger In The Water

The cut I am posting is tagged ‘psychedelic R&B’ and the descriptor is intriguing. Everyone featured in this band is an accomplished jazz musician and it shows. Boundaries have been deliberately blurred until a new, fresh kind of music emerges, which catches your attention because it is familiar but not familiar. The concept, compositions and delightful artwork are those of vocalist Chelsea Prastiti. Her boundless energy is evident here. In Aotearoa, it is not unusual for Jazz-trained musicians to make inroads into Indie-Rock, Soul-Funk and Indie-Pop and do it well, even better (think The Beths). Skilaa will be a band to watch. The band are Chelsea Prastiti (vocals, compositions, artwork), Tom Denison (bass), Adam Tobeck (drums), and Michael Howell (guitar) with guest vocalist Crystal Choi (recorded by Callum Passels).

The ‘Astounding Eyes of Rita’ – Trio Natalino Marchetti, Francesco Savoretti, Mauro Sigura

I have previously posted on Mauro Sigura, an oud improviser. He recently sent me this clip of his trio featuring oud, with accordion and percussion. The tune is a well-known composition by Anouar Brahem, ‘The Astounding Eyes of Rita’. Improvised music like this is prevalent across the Mediterranean region and deserves a wider audience. This is such a lovely tune and so beautifully realised here. Mauro Sigura (oud), Francesca Savoretti (percussioni), Natalino Marchetti (fisarmonica). Recorded in Rome.

The lockdowns won’t stop jazz! To assist musicians who’ve had performances cancelled, get their music heard around the globe. There Jazz Journalists Association created a Jazz on Lockdown: Hear it Here community blog. for more, click through to

The lockdowns won’t stop jazz! To assist musicians who’ve had performances cancelled, get their music heard around the globe. There Jazz Journalists Association created a Jazz on Lockdown: Hear it Here community blog. for more, click through to

Viata

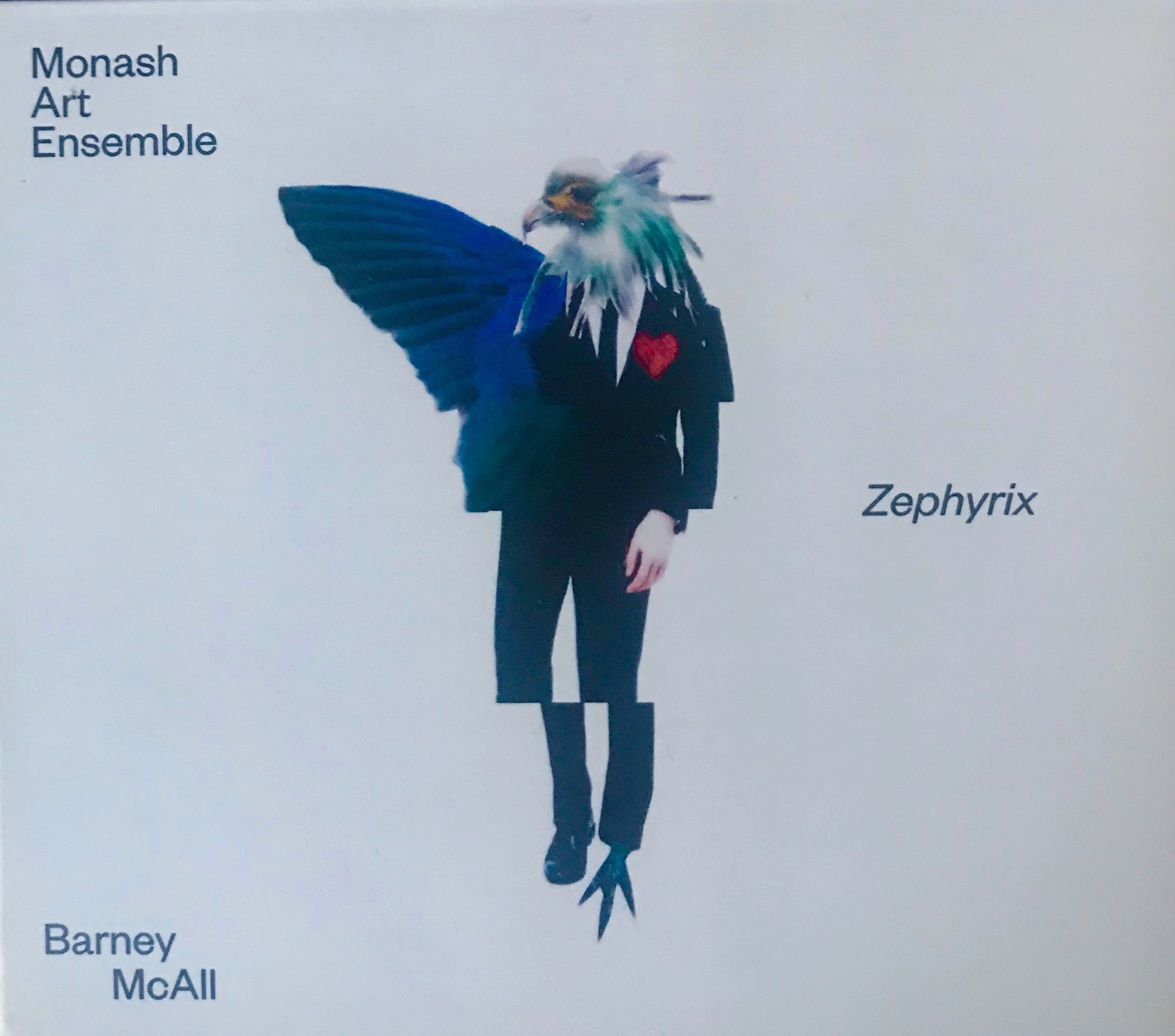

Viata Zephyrix

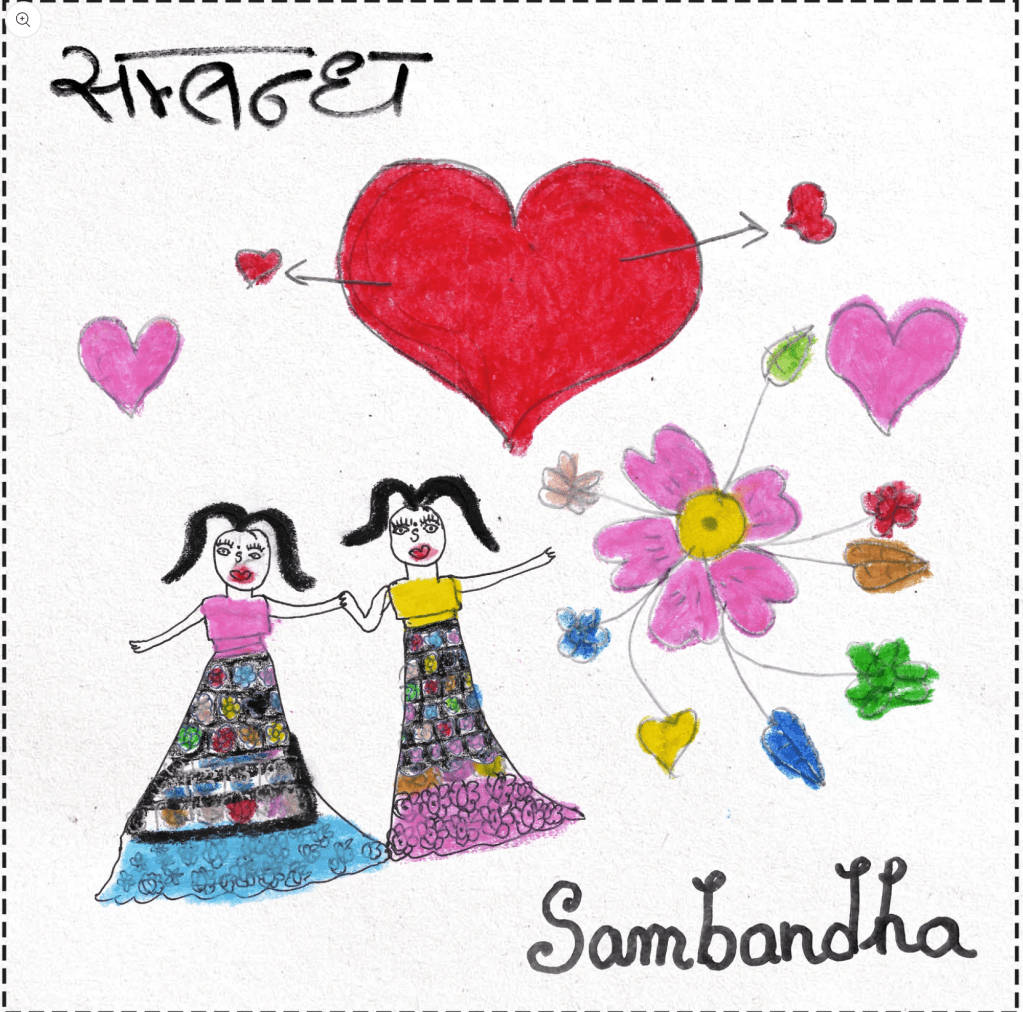

Zephyrix Good Music always says something interesting; it’s a form of communication where a musical statement begins a process and a listener responds. With any innovative musical form, we need to bring something of ourselves to the equation. The more open our ears the better the experience. Gifted improvisers of all cultures understand these fundamentals and because of this they mostly tell old stories in new ways. Rarely and bravely, musicians hit us with stories not yet fixed in the popular imagination. Steve Barry and his collaborators have a foot in both camps. While this is adventurous material, it is also approachable to anyone with open ears. What we heard at the CJC was innovative but the archetypes of all music were located deep in the compositional structure. A careful listening revealed trace elements from composers like Stravinsky or Bley and perhaps even of indigenous music.

Good Music always says something interesting; it’s a form of communication where a musical statement begins a process and a listener responds. With any innovative musical form, we need to bring something of ourselves to the equation. The more open our ears the better the experience. Gifted improvisers of all cultures understand these fundamentals and because of this they mostly tell old stories in new ways. Rarely and bravely, musicians hit us with stories not yet fixed in the popular imagination. Steve Barry and his collaborators have a foot in both camps. While this is adventurous material, it is also approachable to anyone with open ears. What we heard at the CJC was innovative but the archetypes of all music were located deep in the compositional structure. A careful listening revealed trace elements from composers like Stravinsky or Bley and perhaps even of indigenous music.

It was a foolish oversight on my part – I hadn’t visited Melbourne in fifteen years. I had seen quite a few Melbourne improvisers perform in Sydney or Auckland but failed to track them back to their native habitat. The last time I was there, Bennett’s Lane was still a thing, but closed for two weeks. That was the week between Christmas and New Year; that arid Jazzless desert in the live music calendar. With family now residing in Melbourne, I decided to atone for my sins and I headed off while the Jazz calendar was over-flowing with tasty offerings.

It was a foolish oversight on my part – I hadn’t visited Melbourne in fifteen years. I had seen quite a few Melbourne improvisers perform in Sydney or Auckland but failed to track them back to their native habitat. The last time I was there, Bennett’s Lane was still a thing, but closed for two weeks. That was the week between Christmas and New Year; that arid Jazzless desert in the live music calendar. With family now residing in Melbourne, I decided to atone for my sins and I headed off while the Jazz calendar was over-flowing with tasty offerings.

The Australian and New Zealand improvising scenes are a homogenous entity and long may it remain so. If the traffic sometimes appears one-sided, that is a natural consequence of our artists moving to the bigger scene; the exchange benefiting both. Many of those who jump the Tasman do well and they always return for gigs, tours, or sometimes to conduct workshops. Without these exchanges with Australia and beyond, our improvised music scene would be the poorer. This traffic brings us a number of talented Australians, musicians who probably would not have the opportunity to come otherwise; those collegial connections count for something. Drummer Simon Barker is one of those.

The Australian and New Zealand improvising scenes are a homogenous entity and long may it remain so. If the traffic sometimes appears one-sided, that is a natural consequence of our artists moving to the bigger scene; the exchange benefiting both. Many of those who jump the Tasman do well and they always return for gigs, tours, or sometimes to conduct workshops. Without these exchanges with Australia and beyond, our improvised music scene would be the poorer. This traffic brings us a number of talented Australians, musicians who probably would not have the opportunity to come otherwise; those collegial connections count for something. Drummer Simon Barker is one of those. Barker was in Auckland early last year with Carl Dewhurst. Together they are the amazing ‘Showa44’, a duo which I reviewed during their visit. Anyone who follows Barker will know how versatile he is, and above all the musical integrity and originality he brings to whatever situation he is in. Barney McAll’s award-winning ‘Mooroolbark’ and ‘Showa44’ are very different propositions but Barker sits comfortably at the heart of both; of equal importance is his teaching. While in Auckland, he held a workshop at the Auckland University Jazz School and undertook three days of intensive one-on-one teaching with students (and established musicians). Students I spoke to said that they valued the opportunity enormously.

Barker was in Auckland early last year with Carl Dewhurst. Together they are the amazing ‘Showa44’, a duo which I reviewed during their visit. Anyone who follows Barker will know how versatile he is, and above all the musical integrity and originality he brings to whatever situation he is in. Barney McAll’s award-winning ‘Mooroolbark’ and ‘Showa44’ are very different propositions but Barker sits comfortably at the heart of both; of equal importance is his teaching. While in Auckland, he held a workshop at the Auckland University Jazz School and undertook three days of intensive one-on-one teaching with students (and established musicians). Students I spoke to said that they valued the opportunity enormously. The first set featured Barker solo. It is not often that a drummer performs solo and to pull that off requires something beyond mere drum chops. Barker brings something that is uniquely himself to the kit, and he is able to communicate a story, not just a beat. He began with a tribute to an obscure central North Island Polynesian drummer (sadly the name alludes me). He has never met this person but saw a clip of him performing in the traditional Polynesian, polyrhythmic style. He had a traditional wooden drum mounted beside his big tom and working between this and his kit, he created intricate cross rhythms, worthy of a row of skilled drummers.

The first set featured Barker solo. It is not often that a drummer performs solo and to pull that off requires something beyond mere drum chops. Barker brings something that is uniquely himself to the kit, and he is able to communicate a story, not just a beat. He began with a tribute to an obscure central North Island Polynesian drummer (sadly the name alludes me). He has never met this person but saw a clip of him performing in the traditional Polynesian, polyrhythmic style. He had a traditional wooden drum mounted beside his big tom and working between this and his kit, he created intricate cross rhythms, worthy of a row of skilled drummers. His second and shorter piece he described as a chant and it was. The hypnotic intensity carried the audience to the last beat; just as the first piece had. He is not only a storyteller on his instrument but he is capable of creating an orchestral sound. The audience loved it. The second set was something of an impromptu affair but none the less enjoyable for that. Also on stage for that set was Dixon Nacey, Olivier Holland, and Roger Manins. So busy was Barker’s schedule that the quartet had not found time to rehearse. Even the set list was once settled on the bandstand.

His second and shorter piece he described as a chant and it was. The hypnotic intensity carried the audience to the last beat; just as the first piece had. He is not only a storyteller on his instrument but he is capable of creating an orchestral sound. The audience loved it. The second set was something of an impromptu affair but none the less enjoyable for that. Also on stage for that set was Dixon Nacey, Olivier Holland, and Roger Manins. So busy was Barker’s schedule that the quartet had not found time to rehearse. Even the set list was once settled on the bandstand. They began with ‘All the things you are’ and turned it on its head. The introduction performed by Holland and Barker alone was a blast. Drummer and bass exchanging phrases, challenging each other, leavening the exchanges with humour. When Nacey and Manins came in they exposed the bones of the tune. It was well done and in spite of its raw originality, the echoes of the melody hung in the air as implied offerings. The remainder of the set were original compositions and a rendition of the complex but ever popular Oleo (Rollins). Keep visiting Australians, we value you.

They began with ‘All the things you are’ and turned it on its head. The introduction performed by Holland and Barker alone was a blast. Drummer and bass exchanging phrases, challenging each other, leavening the exchanges with humour. When Nacey and Manins came in they exposed the bones of the tune. It was well done and in spite of its raw originality, the echoes of the melody hung in the air as implied offerings. The remainder of the set were original compositions and a rendition of the complex but ever popular Oleo (Rollins). Keep visiting Australians, we value you. When I started attending the CJC, I heard Peter Koopman quite often. He was always impressive, but never a showy guitarist. His approach matched his quiet demeanor, an easy-going manner obscuring a real determination to excel at his craft. Before long he moved to Sydney and although the local Jazz scene laments this musicians rite of passage, we also know it is the right thing. At best, these offshore journeys produce the Mike Nocks and the Matt Penmans, and we all benefit from that.

When I started attending the CJC, I heard Peter Koopman quite often. He was always impressive, but never a showy guitarist. His approach matched his quiet demeanor, an easy-going manner obscuring a real determination to excel at his craft. Before long he moved to Sydney and although the local Jazz scene laments this musicians rite of passage, we also know it is the right thing. At best, these offshore journeys produce the Mike Nocks and the Matt Penmans, and we all benefit from that. We have seen him back in New Zealand a few times during the last five years, but this is his first visit leading a guitar trio. As anticipated, we experienced a more mature Koopman, his guitar work showcasing well-honed skills. Australia is a merciless testing ground for improvising musicians and especially so for guitarists. Working in the same scene as Carl Dewhurst or James Muller, and holding your own, the proof of the pudding. In 2014 Koopman was placed 3rd in the Australian National Jazz Awards, which are held at Wangaratta each year. These awards are fiercely contested and that is no small accomplishment.

We have seen him back in New Zealand a few times during the last five years, but this is his first visit leading a guitar trio. As anticipated, we experienced a more mature Koopman, his guitar work showcasing well-honed skills. Australia is a merciless testing ground for improvising musicians and especially so for guitarists. Working in the same scene as Carl Dewhurst or James Muller, and holding your own, the proof of the pudding. In 2014 Koopman was placed 3rd in the Australian National Jazz Awards, which are held at Wangaratta each year. These awards are fiercely contested and that is no small accomplishment.  The Inner Westies Trio for the New Zealand trip was Peter Koopman (guitar), Max Alduca (bass) and Stephen Thomas (drums). The guitarist and Bass player from West Sydney, the drummer from West Auckland. Alduca is a compelling bass player, and a drawcard on his own. He often includes a touch of tasteful arco bass in his performance. I last saw him when he toured with the ‘Antipodeans’, an innovative young ensemble, populated with musicians from three countries. Alduca made a hit then and reinforced our positive view of him this night. He has a number of gigs about Auckland aside from the CJC gig. A player bursting with originality and with a notable way of engaging with audiences. Nice to see him back and especially in this company.

The Inner Westies Trio for the New Zealand trip was Peter Koopman (guitar), Max Alduca (bass) and Stephen Thomas (drums). The guitarist and Bass player from West Sydney, the drummer from West Auckland. Alduca is a compelling bass player, and a drawcard on his own. He often includes a touch of tasteful arco bass in his performance. I last saw him when he toured with the ‘Antipodeans’, an innovative young ensemble, populated with musicians from three countries. Alduca made a hit then and reinforced our positive view of him this night. He has a number of gigs about Auckland aside from the CJC gig. A player bursting with originality and with a notable way of engaging with audiences. Nice to see him back and especially in this company.

Auckland spoils us with long runs of clement weather, but when winter hits we suffer. Having effectively avoided any meaningful autumn we suddenly plunged into a week of cold wet days. There was no better time for the Michel Benebig/Carl Lockett band to arrive. As we grooved to the music, a warmth flooded our bodies within minutes. Nothing invokes warmth like a well oiled B3 groove unit and the Benebig/Locket band is as good as it gets. The icing on the cake was seeing Shem with them. A singer with incredible modulation skills and perfect pitch, able to convey the nuances of emotion with a casual glance or a single note. The way she moves from the upper register to the midrange, silken.

Auckland spoils us with long runs of clement weather, but when winter hits we suffer. Having effectively avoided any meaningful autumn we suddenly plunged into a week of cold wet days. There was no better time for the Michel Benebig/Carl Lockett band to arrive. As we grooved to the music, a warmth flooded our bodies within minutes. Nothing invokes warmth like a well oiled B3 groove unit and the Benebig/Locket band is as good as it gets. The icing on the cake was seeing Shem with them. A singer with incredible modulation skills and perfect pitch, able to convey the nuances of emotion with a casual glance or a single note. The way she moves from the upper register to the midrange, silken. Michel Benebig has been travelling to New Zealand for years, and his connection with the principals of the UoA Jazz school has been a boon for us. He generally brings his partner Shem with him, but last time work commitments in her native New Caledonia kept her at home. Michel just gets better and better and the way his pedal work and hands create contrasts and tension defies belief. It is therefore not surprising that Michel attracts top rated guitarists or saxophonists to his bands. The best of our local groove guitarists have often featured and a growing number of stand-out American artists (see earlier posts on this band). Of these, the New York guitarist Carl Locket is of particular note. I first heard Lockett in San Francisco four years ago and he mesmerised me with his deep bluesy lines and time feel. Although comfortable in a number of genres, he is the ideal choice for an organ/guitar groove unit.

Michel Benebig has been travelling to New Zealand for years, and his connection with the principals of the UoA Jazz school has been a boon for us. He generally brings his partner Shem with him, but last time work commitments in her native New Caledonia kept her at home. Michel just gets better and better and the way his pedal work and hands create contrasts and tension defies belief. It is therefore not surprising that Michel attracts top rated guitarists or saxophonists to his bands. The best of our local groove guitarists have often featured and a growing number of stand-out American artists (see earlier posts on this band). Of these, the New York guitarist Carl Locket is of particular note. I first heard Lockett in San Francisco four years ago and he mesmerised me with his deep bluesy lines and time feel. Although comfortable in a number of genres, he is the ideal choice for an organ/guitar groove unit. The band played material from their recent album (mostly Benebig’s compositions) and a few standards. There were also compositions by Shem Benebig. Their approach to arranging standards is appealing – numbers like Johnny Mandel’s ‘Suicide is Painless’ are transformed into groove excellence. We heard that number performed at the band’s last visit and the audience loved to hear it repeated. This visit, we heard a terrific interpretation of ‘Angel Eyes’ (Matt Dennis). I confess that this is one of my favourite standards (Ella regarded it as her favourite ballad). Anita O’day performed it beautifully as did Frank Sinatra and Nat Cole. The only groove version I can recall is the relatively unknown Gene Ammons cut (a bonus number added in later years to his ‘Boss Tenor’ album with organist Johnny ‘Hammond’ Smith). That version took the tune at a very slow pace, so slow in fact that you initially wondered if Ammons had nodded off before he came in. It was wonderful for all that (who can resist Ammons).

The band played material from their recent album (mostly Benebig’s compositions) and a few standards. There were also compositions by Shem Benebig. Their approach to arranging standards is appealing – numbers like Johnny Mandel’s ‘Suicide is Painless’ are transformed into groove excellence. We heard that number performed at the band’s last visit and the audience loved to hear it repeated. This visit, we heard a terrific interpretation of ‘Angel Eyes’ (Matt Dennis). I confess that this is one of my favourite standards (Ella regarded it as her favourite ballad). Anita O’day performed it beautifully as did Frank Sinatra and Nat Cole. The only groove version I can recall is the relatively unknown Gene Ammons cut (a bonus number added in later years to his ‘Boss Tenor’ album with organist Johnny ‘Hammond’ Smith). That version took the tune at a very slow pace, so slow in fact that you initially wondered if Ammons had nodded off before he came in. It was wonderful for all that (who can resist Ammons). The band began the tune at a slow pace (but not as slow as Ammons), then once through, picking up the tempo, the band settling into a deeper groove, drummer Samsom and the guitarist really locking together, giving the Benebig’s room to create magic. That locked-in beat is often at the heart of an organ-guitar unit and when done well it adds bottom to the sound. Locket’s style of comping is the key to that effect, the entry point for the drummer, the way the guitarist lays back on the beat and comps in a particular way. Samsom heard and responded as I knew he would. He is a groove merchant at heart. On tenor saxophone, Roger Manins was on home turf. Dreamily caressing the melody before his solo.

The band began the tune at a slow pace (but not as slow as Ammons), then once through, picking up the tempo, the band settling into a deeper groove, drummer Samsom and the guitarist really locking together, giving the Benebig’s room to create magic. That locked-in beat is often at the heart of an organ-guitar unit and when done well it adds bottom to the sound. Locket’s style of comping is the key to that effect, the entry point for the drummer, the way the guitarist lays back on the beat and comps in a particular way. Samsom heard and responded as I knew he would. He is a groove merchant at heart. On tenor saxophone, Roger Manins was on home turf. Dreamily caressing the melody before his solo. As I write this it is International Jazz Day, a UNESCO sponsored day honouring the diversity and depth of the world improvising scene. It was, therefore, serendipitous that Carl Dewhurst and Simon Barker brought ‘Showa 44’ to town – especially in the days immediately preceding the big celebration. This gig offered actual proof that the restless exploration of free-spirited improvisers, lives on undiminished. I have sometimes heard die-hard Jazz fans questioning free improvisation, believing that the music reached an unassailable peak in their favourite era. To quote Dexter Gordon. “Jazz is a living music. It is unafraid …. It doesn’t stand still, that’s how it survives“. While a particular coterie prefers their comfort zone, the music moves on without them. Younger ears hear the call and new audiences form. Life is a continuum and great art draws upon the energies about it for momentum. Improvised music is not a display in a history museum.

As I write this it is International Jazz Day, a UNESCO sponsored day honouring the diversity and depth of the world improvising scene. It was, therefore, serendipitous that Carl Dewhurst and Simon Barker brought ‘Showa 44’ to town – especially in the days immediately preceding the big celebration. This gig offered actual proof that the restless exploration of free-spirited improvisers, lives on undiminished. I have sometimes heard die-hard Jazz fans questioning free improvisation, believing that the music reached an unassailable peak in their favourite era. To quote Dexter Gordon. “Jazz is a living music. It is unafraid …. It doesn’t stand still, that’s how it survives“. While a particular coterie prefers their comfort zone, the music moves on without them. Younger ears hear the call and new audiences form. Life is a continuum and great art draws upon the energies about it for momentum. Improvised music is not a display in a history museum. It is through listening to innovative live music that our ears sharpen. When sitting in front of a band like this the mysteries of sound become visceral. This was an extraordinary gig, at times loud and confronting, mesmerising, ambient and always cram-packed with subtlety. Fragments of melodic invention and patterns formed. Then subtly, without our realising it, they were gone, tantalising, promise-filled but illusory. We seldom noticed these micro changes as they were affected so skillfully – form and space changing minute by minute, new and yet strangely familiar – briefly reappearing as quicksilver loops before reinventing themselves.

It is through listening to innovative live music that our ears sharpen. When sitting in front of a band like this the mysteries of sound become visceral. This was an extraordinary gig, at times loud and confronting, mesmerising, ambient and always cram-packed with subtlety. Fragments of melodic invention and patterns formed. Then subtly, without our realising it, they were gone, tantalising, promise-filled but illusory. We seldom noticed these micro changes as they were affected so skillfully – form and space changing minute by minute, new and yet strangely familiar – briefly reappearing as quicksilver loops before reinventing themselves. With the constraints of form and melody loosened new possibilities emerge. In inexperienced hands, the difficulties can overwhelm. In the hands of artists like these the freedom gives them superpowers. Time is displaced, tonality split into a prism of sound, patterns turned inside out. The first set was a single duo piece, ‘Improvisation one’ – unfolding over an hour and a quarter; Dewhurst and Barker, barely visible in the low light. This was about sculpting sound and seeing the musicians in shadow added a veneer of mystique. Dewhurst began quietly, his solid body guitar lying face up on his lap. The sound came in waves as he stroked and pushed at the strings, moving a slide – ever so slightly at first, causing microtonal shifts or new harmonics to form, modulating, striking the strings with a mallet or the palm of his hand. The illusion created, was of a single drone repeating. In reality, the sound was orchestral. As you listened, really listened, microtones, semitones and the occasional interval appeared over the drone. Barker providing multiple dimensions and astonishing colour, responding, reacting, crafting new directions.

With the constraints of form and melody loosened new possibilities emerge. In inexperienced hands, the difficulties can overwhelm. In the hands of artists like these the freedom gives them superpowers. Time is displaced, tonality split into a prism of sound, patterns turned inside out. The first set was a single duo piece, ‘Improvisation one’ – unfolding over an hour and a quarter; Dewhurst and Barker, barely visible in the low light. This was about sculpting sound and seeing the musicians in shadow added a veneer of mystique. Dewhurst began quietly, his solid body guitar lying face up on his lap. The sound came in waves as he stroked and pushed at the strings, moving a slide – ever so slightly at first, causing microtonal shifts or new harmonics to form, modulating, striking the strings with a mallet or the palm of his hand. The illusion created, was of a single drone repeating. In reality, the sound was orchestral. As you listened, really listened, microtones, semitones and the occasional interval appeared over the drone. Barker providing multiple dimensions and astonishing colour, responding, reacting, crafting new directions. In this context, the drummer took on many roles, a foil to the guitarist, creating silken whispers, insistent flurries of beats and at times building to a heart-stopping crescendo. I found this music riveting and the audience obviously shared my view. In the quiet passages, you could hear a pin drop. If that’s not an indication of the musical maturity of modern Jazz audiences, nothing is. One of the prime functions of art is to confront, to challenge complacency. This music did that while gently leading us deeper inside sound itself. No one at the CJC regretted being on this journey. This is territory loosely mapped by the UK guitarist Derek Bailey, the Norwegian guitarist Aivind Aaset and the American guitarist Mary Halvorson. They may take a similar path, but this felt original, perhaps it is an Australian sound (with a Kiwi twist in Manins). The long multifaceted trance-like drones suggest that.

In this context, the drummer took on many roles, a foil to the guitarist, creating silken whispers, insistent flurries of beats and at times building to a heart-stopping crescendo. I found this music riveting and the audience obviously shared my view. In the quiet passages, you could hear a pin drop. If that’s not an indication of the musical maturity of modern Jazz audiences, nothing is. One of the prime functions of art is to confront, to challenge complacency. This music did that while gently leading us deeper inside sound itself. No one at the CJC regretted being on this journey. This is territory loosely mapped by the UK guitarist Derek Bailey, the Norwegian guitarist Aivind Aaset and the American guitarist Mary Halvorson. They may take a similar path, but this felt original, perhaps it is an Australian sound (with a Kiwi twist in Manins). The long multifaceted trance-like drones suggest that.  The second set was shorter, ‘Improvisation two’ had Roger Manins aboard. I should be immune to Manins surprises but he frequently catches me off guard. His breadth and depth appear limitless. ‘Improvisation Two’ began with a broader melodic palette. Dewhurst and Barker set the piece up and when Manins came in there was a stunning ECM feel created. Barker tap-tapping the high-hat and ride. Achingly beautiful phases hung in the air – then, surprisingly they eluded us, unravelling as Manins dug deeper – dissecting them note by note. These interactions give us a clue as to how this music works, each musician playing a phrase or pattern and then re-shaping it, passing the baton endlessly.

The second set was shorter, ‘Improvisation two’ had Roger Manins aboard. I should be immune to Manins surprises but he frequently catches me off guard. His breadth and depth appear limitless. ‘Improvisation Two’ began with a broader melodic palette. Dewhurst and Barker set the piece up and when Manins came in there was a stunning ECM feel created. Barker tap-tapping the high-hat and ride. Achingly beautiful phases hung in the air – then, surprisingly they eluded us, unravelling as Manins dug deeper – dissecting them note by note. These interactions give us a clue as to how this music works, each musician playing a phrase or pattern and then re-shaping it, passing the baton endlessly.

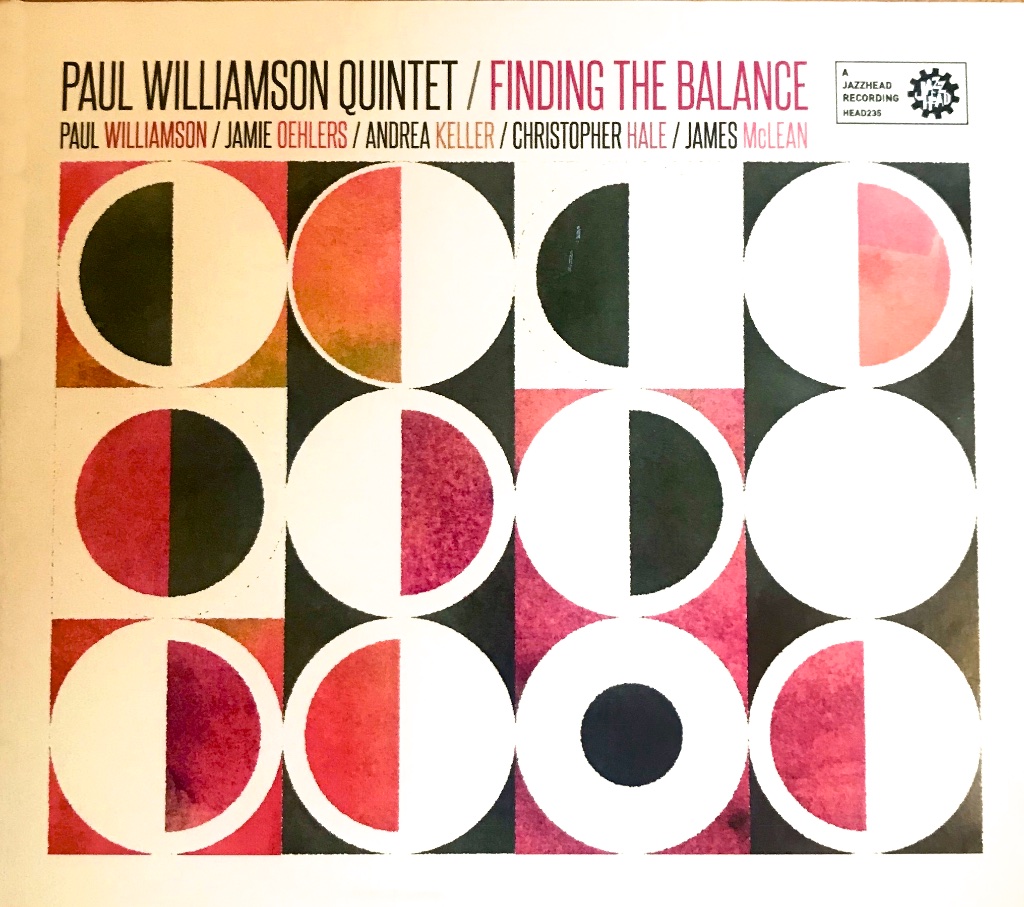

When the word gets about that a Jamie Oehlers gig is imminent, excitement mounts. Having turned people away last year, due to a capacity audience, the CJC offered two sessions this time. As expected, both were well attended. Oehlers is highly regarded in the Jazz world and it is not surprising. His astonishing mastery of the tenor saxophone is central to his appeal, but it is more than that. Every note he plays sounds authentic as if no other note could ever replace it, and all conveying a sense of musical humanism.

When the word gets about that a Jamie Oehlers gig is imminent, excitement mounts. Having turned people away last year, due to a capacity audience, the CJC offered two sessions this time. As expected, both were well attended. Oehlers is highly regarded in the Jazz world and it is not surprising. His astonishing mastery of the tenor saxophone is central to his appeal, but it is more than that. Every note he plays sounds authentic as if no other note could ever replace it, and all conveying a sense of musical humanism. Oehlers has a new album out titled ‘The burden of memory‘ and we heard many of the pieces as the sets unfolded. Accompanying him on the album is a dream rhythm section: Paul Grabowsky on piano, Reuben Rogers on bass and Eric Harland on drums. Each a heavyweight and living up to their formidable reputations. For the Auckland gig, there was Kevin Field on piano, Olivier Holland on bass and Frank Gibson Jr on drums. Jumping in where Grabowsky, Rogers, and Harland had gone was no doubt daunting but they pulled it off in style. All played exceptionally well, but Gibson was a standout. The exchanges between him and Oehlers memorable. These men have history and the old conversations were clearly rekindled on the bandstand. Roger Manins joined Oehlers for the last number of each set and the two dueled as only they can. Weaving skillfully around each other and sounding like two halves of a whole; grinning like Cheshire cats.

Oehlers has a new album out titled ‘The burden of memory‘ and we heard many of the pieces as the sets unfolded. Accompanying him on the album is a dream rhythm section: Paul Grabowsky on piano, Reuben Rogers on bass and Eric Harland on drums. Each a heavyweight and living up to their formidable reputations. For the Auckland gig, there was Kevin Field on piano, Olivier Holland on bass and Frank Gibson Jr on drums. Jumping in where Grabowsky, Rogers, and Harland had gone was no doubt daunting but they pulled it off in style. All played exceptionally well, but Gibson was a standout. The exchanges between him and Oehlers memorable. These men have history and the old conversations were clearly rekindled on the bandstand. Roger Manins joined Oehlers for the last number of each set and the two dueled as only they can. Weaving skillfully around each other and sounding like two halves of a whole; grinning like Cheshire cats. The album title and the song titles speak clearly of the musicians thought processes. He talks of his motivations and his horn takes us there. The burden of memory is a phrase he heard while listening to talkback radio and it resonated with him. He thinks deeply, examines the world about him and this communicates throughout the album. The second track ‘Armistice’ is a good example, possessing a melancholic beauty, and while it throws up the obvious images of a war ending, it also speaks of families and the tentative steps towards new possibilities.

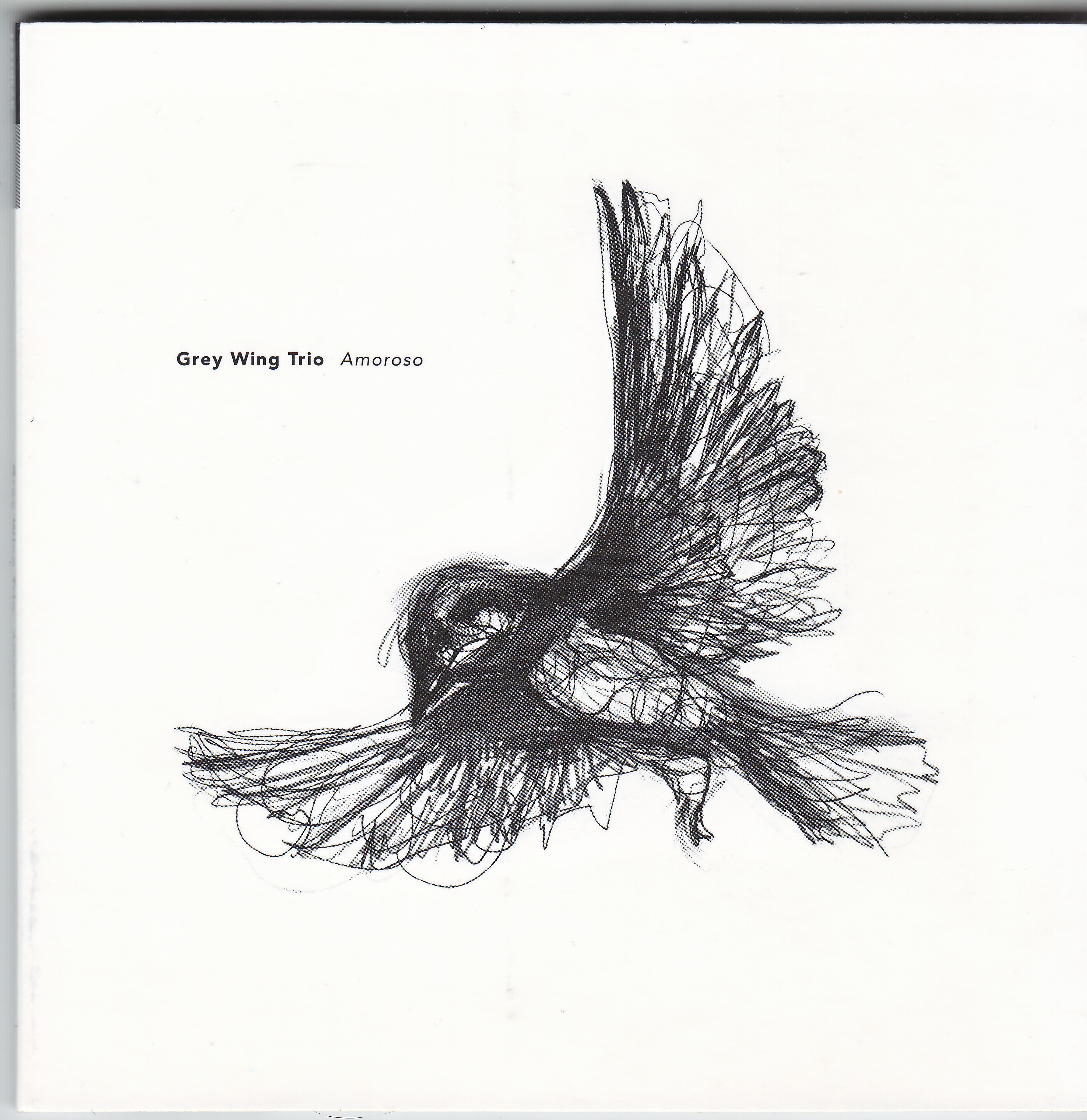

The album title and the song titles speak clearly of the musicians thought processes. He talks of his motivations and his horn takes us there. The burden of memory is a phrase he heard while listening to talkback radio and it resonated with him. He thinks deeply, examines the world about him and this communicates throughout the album. The second track ‘Armistice’ is a good example, possessing a melancholic beauty, and while it throws up the obvious images of a war ending, it also speaks of families and the tentative steps towards new possibilities. It is not very often that an album like this comes along and more’s the pity. This is an album for those who are properly engaged, who listen deeply; offering ample rewards to those who pay due attention. While there is a hint of the freedom of the 1961-62 Giuffre/Bley/Swallow albums, this is an album of the now. It tells a modern Australian story while claiming a portion of the space occupied by the sparse Nordic improvisers. People might find this darker approach unexpected as the Australian landscape resonates bright light and pastel colours. While not the norm there are recent precedents such as the astonishingly atmospheric ‘Kindred Spirits’ by Mike Nock. Pianist Luke Sweeting shows us from the first few notes that he truly understands form and dynamics. As he moves about the piano his fingers tease out endless shades of colour; the sort found in the shadows. The name Grey Wing Trio is apt too, because the subtlety of the shadings are endless here. Like the wing of a sparrow, what appears as mono-toned becomes multi-hued upon closer examination.

It is not very often that an album like this comes along and more’s the pity. This is an album for those who are properly engaged, who listen deeply; offering ample rewards to those who pay due attention. While there is a hint of the freedom of the 1961-62 Giuffre/Bley/Swallow albums, this is an album of the now. It tells a modern Australian story while claiming a portion of the space occupied by the sparse Nordic improvisers. People might find this darker approach unexpected as the Australian landscape resonates bright light and pastel colours. While not the norm there are recent precedents such as the astonishingly atmospheric ‘Kindred Spirits’ by Mike Nock. Pianist Luke Sweeting shows us from the first few notes that he truly understands form and dynamics. As he moves about the piano his fingers tease out endless shades of colour; the sort found in the shadows. The name Grey Wing Trio is apt too, because the subtlety of the shadings are endless here. Like the wing of a sparrow, what appears as mono-toned becomes multi-hued upon closer examination. I knew of Matt McMahon long before I met him in the Foundry 616. Australian and New Zealand Jazz lovers respect him as an artist and his name often comes up when improvising musicians talk. In 2008 I picked up a copy of his Ellipsis album during a visit to Sydney. My album collection then as now, was out of control and so after listening to it, I filed the album with the intention of obtaining more by the artist later. Because my cataloging skills are poorly developed it soon slipped out of sight and did not resurface until 2015. That was the year I met McMahon at The Foundry. His gig was as the regular pianist and arranger/co-composer for the Vince Jones band. I liked his playing and noted my impressions of man and pianist on the back of my program; ‘friendly, of quiet demeanour – a pianist with a deft touch – uses beautiful crisp voicings. The perfect accompanist, serving the singer and the song and never his ego‘. We talked for some time after the gig and before I left he handed me a copy of his ‘The Voyage of William and Mary’ album.

I knew of Matt McMahon long before I met him in the Foundry 616. Australian and New Zealand Jazz lovers respect him as an artist and his name often comes up when improvising musicians talk. In 2008 I picked up a copy of his Ellipsis album during a visit to Sydney. My album collection then as now, was out of control and so after listening to it, I filed the album with the intention of obtaining more by the artist later. Because my cataloging skills are poorly developed it soon slipped out of sight and did not resurface until 2015. That was the year I met McMahon at The Foundry. His gig was as the regular pianist and arranger/co-composer for the Vince Jones band. I liked his playing and noted my impressions of man and pianist on the back of my program; ‘friendly, of quiet demeanour – a pianist with a deft touch – uses beautiful crisp voicings. The perfect accompanist, serving the singer and the song and never his ego‘. We talked for some time after the gig and before I left he handed me a copy of his ‘The Voyage of William and Mary’ album.

Due to the timing of the Chris Cody album ‘Not My Lover’, some jumped to the conclusion that his Jazz love letter to Paris was in response to the recent atrocities. In fact Cody recorded it well before those tragic events and much to the relief of family and friends he was safely in Australia at the time. The City of Light has the strongest of Jazz associations and Cody captures that intimate relationship perfectly. You can feel the ebb and flow of the city’s life running through his fingertips as he plays. The beauty of the architecture, the elegant Seine, the mad driving through the twisted maze of streets. Through his perceptive lens we gain a sense of the city which for hundreds of years has welcomed visiting creative artists to its heart; regardless of creed or colour. We also catch a fleeting glimpse of the harsher realities hidden behind the gorgeous facade.

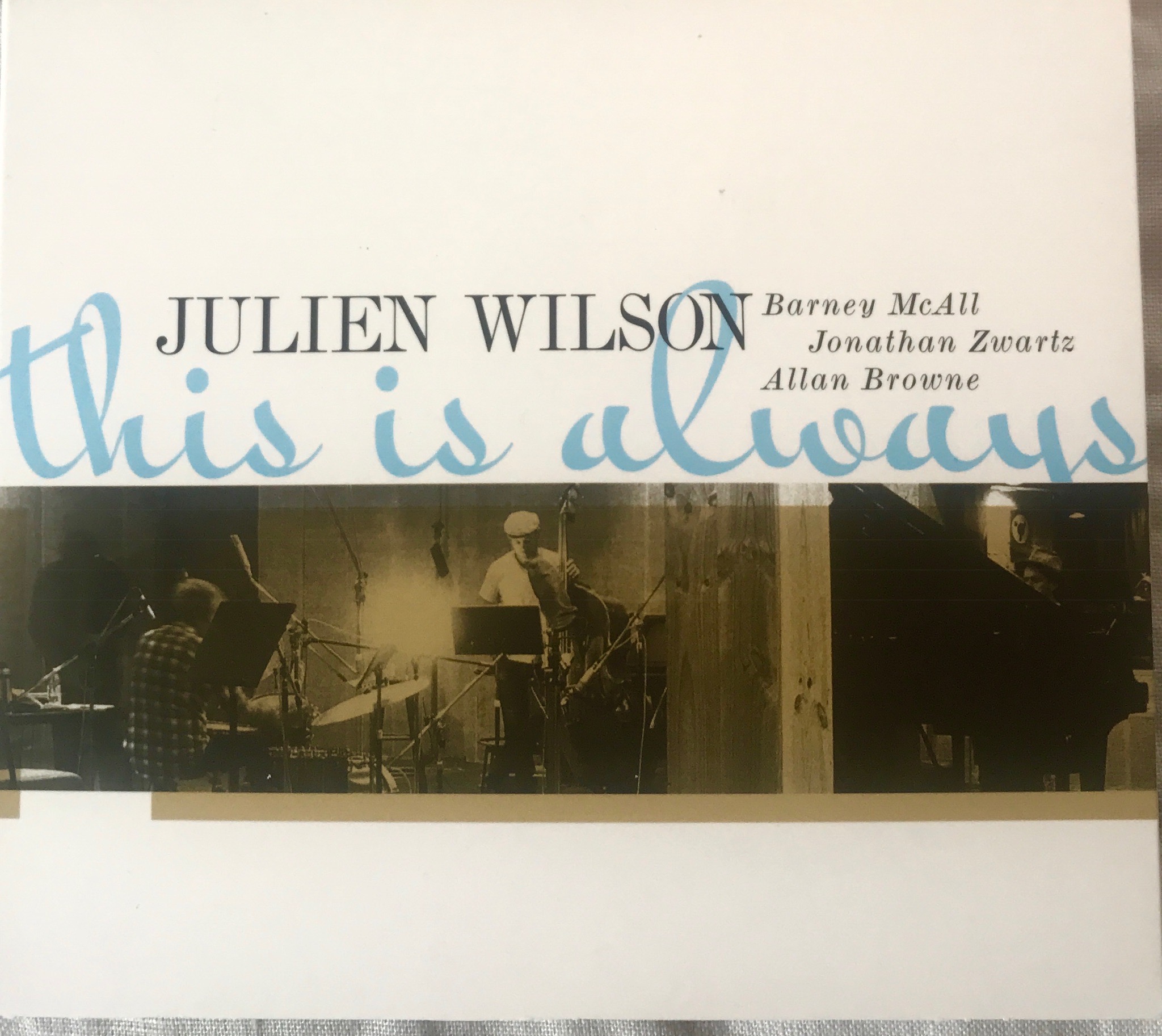

Due to the timing of the Chris Cody album ‘Not My Lover’, some jumped to the conclusion that his Jazz love letter to Paris was in response to the recent atrocities. In fact Cody recorded it well before those tragic events and much to the relief of family and friends he was safely in Australia at the time. The City of Light has the strongest of Jazz associations and Cody captures that intimate relationship perfectly. You can feel the ebb and flow of the city’s life running through his fingertips as he plays. The beauty of the architecture, the elegant Seine, the mad driving through the twisted maze of streets. Through his perceptive lens we gain a sense of the city which for hundreds of years has welcomed visiting creative artists to its heart; regardless of creed or colour. We also catch a fleeting glimpse of the harsher realities hidden behind the gorgeous facade. Mooroolbark is a place, an album and a state of mind. It is an intersection of worlds and a testament to Barney McAll’s writing skills .

Mooroolbark is a place, an album and a state of mind. It is an intersection of worlds and a testament to Barney McAll’s writing skills . #ASIO stands for the Australian Symbiotic Improvisers Orbit, but even in the title the story deepens? Another ASIO comes to mind, as hard-won Australian freedoms vanish in the eternal quest for security. At a pre-release gig in Sydney’s Basement the band donned high-viz vests with #ASIO stencilled on them; high visibility music juxtaposed with secretive worlds. This #ASIO has some answers. The landscape of McAll’s new album ‘Mooroolbark’ is littered with these potent images and if you let your preconceptions go, they will come to you. These musical parables are modern ‘song lines’; age old stories told afresh. ‘Mooroolbark’ completes a circle. A return to familiar physical and spiritual landscapes. A reappraisal of the journey with old musical friends.

#ASIO stands for the Australian Symbiotic Improvisers Orbit, but even in the title the story deepens? Another ASIO comes to mind, as hard-won Australian freedoms vanish in the eternal quest for security. At a pre-release gig in Sydney’s Basement the band donned high-viz vests with #ASIO stencilled on them; high visibility music juxtaposed with secretive worlds. This #ASIO has some answers. The landscape of McAll’s new album ‘Mooroolbark’ is littered with these potent images and if you let your preconceptions go, they will come to you. These musical parables are modern ‘song lines’; age old stories told afresh. ‘Mooroolbark’ completes a circle. A return to familiar physical and spiritual landscapes. A reappraisal of the journey with old musical friends. This unit performs as if they are one entity. Every note serves the project rather than the individuals. The sum is greater than its considerably impressive parts. I have seen McAll perform a number of times and his sense of dynamics is always impressive He can favour the darkly percussive; using those trademark voicings to reel us in, then just as suddenly turn on a dime and with the lightest of touch occupy a gentle minimalism. On Mooroolbark everyone’s touch is light and airy, open space between notes, a crystal clarity that surprisingly yields an almost orchestral feel. Avoiding an excess of notes and making a virtue out of this is especially evident as they play off the ostinato passages (i.e ‘Non Compliance).

This unit performs as if they are one entity. Every note serves the project rather than the individuals. The sum is greater than its considerably impressive parts. I have seen McAll perform a number of times and his sense of dynamics is always impressive He can favour the darkly percussive; using those trademark voicings to reel us in, then just as suddenly turn on a dime and with the lightest of touch occupy a gentle minimalism. On Mooroolbark everyone’s touch is light and airy, open space between notes, a crystal clarity that surprisingly yields an almost orchestral feel. Avoiding an excess of notes and making a virtue out of this is especially evident as they play off the ostinato passages (i.e ‘Non Compliance). A transformation has occurred with ‘Non Compliance’; morphing from a tour de force trio piece into an other-worldly trippy sonic exploration. All of the musicians fit perfectly into the mix and this is a tribute to the arrangements and to the artists. Zwartz (an expat Kiwi who has a strong presence here) holds the groove to perfection and the drummers and percussionists, far from getting in each others way, lay down subtle interactive layers; revealing texture and colour. Barker on drums and percussion is highly respected on the Australian scene (as are all of these musicians). Adding the New York percussionist Mino Cinelu gives that added punch. On tracks 6 & 7 noted trombonist Shannon Barnett adds her magic and Hamish Stewart is on drums for the last track.

A transformation has occurred with ‘Non Compliance’; morphing from a tour de force trio piece into an other-worldly trippy sonic exploration. All of the musicians fit perfectly into the mix and this is a tribute to the arrangements and to the artists. Zwartz (an expat Kiwi who has a strong presence here) holds the groove to perfection and the drummers and percussionists, far from getting in each others way, lay down subtle interactive layers; revealing texture and colour. Barker on drums and percussion is highly respected on the Australian scene (as are all of these musicians). Adding the New York percussionist Mino Cinelu gives that added punch. On tracks 6 & 7 noted trombonist Shannon Barnett adds her magic and Hamish Stewart is on drums for the last track. Barney McAll is an award-winning, Grammy nominated Jazz Musician based in New York. He was recently awarded a one year Peggy Glanville-Hicks Composers Residency and he currently resides at the Paddington residency house in Sydney, Australia.

Barney McAll is an award-winning, Grammy nominated Jazz Musician based in New York. He was recently awarded a one year Peggy Glanville-Hicks Composers Residency and he currently resides at the Paddington residency house in Sydney, Australia.