While not located on the Jazz touring circuit in the way Europe is, New Zealand gets some surprising and unexpected treats throughout the year. This was certainly one of them. Because I’ve been travelling recently, I had not noticed this gig coming up and it caught me quite off guard. From time to time I’ve heard mention of the New Zealand born composer and saxophonist Hayden Chisholm, but I had never heard him play. The little that I did know, was that he’d lived in Europe for many years and that he’d been a microtonal innovator. His CV reveals an amazing diversity of achievements and among them; teaching, composing for large ensembles, recording around the world, film soundtrack scoring, festival directing, touring extensively and collaborating with installation artists. He is obviously not a musician to be pigeonholed easily and my expectations inclined me toward multi-phonic explorations or something akin to the wonderful Bley /Giuffre/Swallow ’61 trio’. What I heard was closer to the equally wonderful Bley (Karla)/Swallow/Shepherd trio.

While not located on the Jazz touring circuit in the way Europe is, New Zealand gets some surprising and unexpected treats throughout the year. This was certainly one of them. Because I’ve been travelling recently, I had not noticed this gig coming up and it caught me quite off guard. From time to time I’ve heard mention of the New Zealand born composer and saxophonist Hayden Chisholm, but I had never heard him play. The little that I did know, was that he’d lived in Europe for many years and that he’d been a microtonal innovator. His CV reveals an amazing diversity of achievements and among them; teaching, composing for large ensembles, recording around the world, film soundtrack scoring, festival directing, touring extensively and collaborating with installation artists. He is obviously not a musician to be pigeonholed easily and my expectations inclined me toward multi-phonic explorations or something akin to the wonderful Bley /Giuffre/Swallow ’61 trio’. What I heard was closer to the equally wonderful Bley (Karla)/Swallow/Shepherd trio. The gig subsumed us in pure unalloyed ballad beauty – beauty of a kind that is exceedingly rare. The programme (with one exception) was of original ballads; pieces composed by either Chisholm or Norman Meehan. Meehan was exactly the right pianist for this gig – a tasteful musician who knows when to lay out, and who never over-ornaments. His sensitivity and minimalist approach creating a bigger implied sound; each note or voicing inviting the audience deeper into an unfolding story. Later when I commented on this he repeated Paul Bley’s advice, “If somebody else sounds good, you’re not needed. So you are like a doctor with a little black bag coming to a record date” (from ‘Time will Tell’ Meehan). Paul Dyne on bass was the ideal foil for Chisholm and Meehan. Again he made each note count without busyness. Because this was an acoustic trio with the piano and saxophone unmiked, the resonance of the bass carried more weight, every harmonic adding a subtle layer. With Meehan playing so sparsely and Chisholm sailing in the clean air above, the subtlties of the soundscape were liberated until the room sang.

The gig subsumed us in pure unalloyed ballad beauty – beauty of a kind that is exceedingly rare. The programme (with one exception) was of original ballads; pieces composed by either Chisholm or Norman Meehan. Meehan was exactly the right pianist for this gig – a tasteful musician who knows when to lay out, and who never over-ornaments. His sensitivity and minimalist approach creating a bigger implied sound; each note or voicing inviting the audience deeper into an unfolding story. Later when I commented on this he repeated Paul Bley’s advice, “If somebody else sounds good, you’re not needed. So you are like a doctor with a little black bag coming to a record date” (from ‘Time will Tell’ Meehan). Paul Dyne on bass was the ideal foil for Chisholm and Meehan. Again he made each note count without busyness. Because this was an acoustic trio with the piano and saxophone unmiked, the resonance of the bass carried more weight, every harmonic adding a subtle layer. With Meehan playing so sparsely and Chisholm sailing in the clean air above, the subtlties of the soundscape were liberated until the room sang. The compositions were varied but all were marvellous. Some so gorgeous as to take the breath away – others possessing edge – all beautifully constructed. The trio worked as an effective unit, but the Chisholm effect was inescapable. The man is simply exceptional, his lines, phrasing and tone jaw dropping. I have no doubt that his technical skills are second to none, but listening to him you never give that a thought. Every musical utterance plunged deep into your soul in the way a Konitz line does. Chisholm is quite original and modern but I fancied that I heard some faint echoes of the great altoists on Wednesday night. Perhaps that was just my imagination, but Lee Konitz (and surprisingly to me), even Art Pepper came mind; especially during Meehan’s wonderfully soulful tune ‘Nick Van Diyk’. I have posted that clip (which is bookended with a lovely Chisholm tune ‘In Day Light Mourning’, where he plays a lament against a drone). The lament references the music of India and Japan, utilising extended technique (Chisholm has studied in both countries).

The compositions were varied but all were marvellous. Some so gorgeous as to take the breath away – others possessing edge – all beautifully constructed. The trio worked as an effective unit, but the Chisholm effect was inescapable. The man is simply exceptional, his lines, phrasing and tone jaw dropping. I have no doubt that his technical skills are second to none, but listening to him you never give that a thought. Every musical utterance plunged deep into your soul in the way a Konitz line does. Chisholm is quite original and modern but I fancied that I heard some faint echoes of the great altoists on Wednesday night. Perhaps that was just my imagination, but Lee Konitz (and surprisingly to me), even Art Pepper came mind; especially during Meehan’s wonderfully soulful tune ‘Nick Van Diyk’. I have posted that clip (which is bookended with a lovely Chisholm tune ‘In Day Light Mourning’, where he plays a lament against a drone). The lament references the music of India and Japan, utilising extended technique (Chisholm has studied in both countries).  It was one of those concerts that made you feel lucky. The sort of concert that you will recall in later years and regale those who missed it with vivid descriptions – enough to make them green with envy. For those who missed the gig or for those who want to relive it, the trio are recording this week. I will keep you posted on that and on where to obtain the album. In addition Norman Meehan has a new book out – a history of New Zealand Jazz. That can be ordered through any main street book outlet (my order is in).

It was one of those concerts that made you feel lucky. The sort of concert that you will recall in later years and regale those who missed it with vivid descriptions – enough to make them green with envy. For those who missed the gig or for those who want to relive it, the trio are recording this week. I will keep you posted on that and on where to obtain the album. In addition Norman Meehan has a new book out – a history of New Zealand Jazz. That can be ordered through any main street book outlet (my order is in).

Hayden Chisholm Trio; Hayden Chisholm (alto saxophone, compositions), Norman Meehan (piano, compositions), Paul Dyne (upright bass) – CJC (Creative Jazz Club), Kenneth Myers Centre, Shortland Street, Auckland 23rd November 2016.

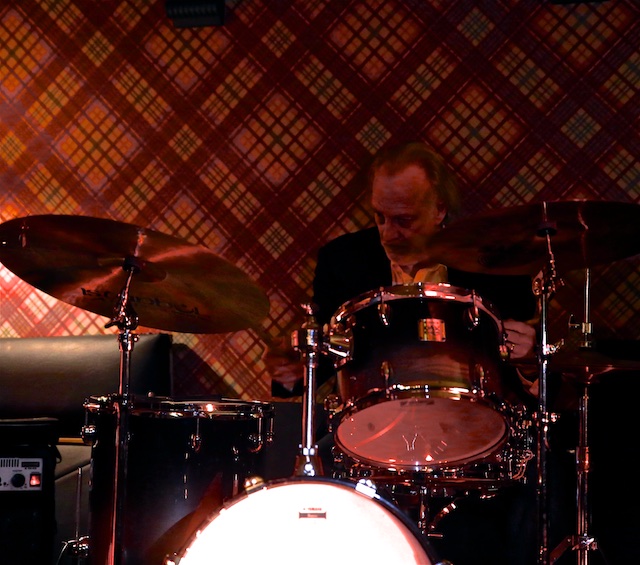

Frank Gibson is a drummer of international repute, a sideman, educator and bandleader. While he is a versatile drummer, his predilection is for bebop and hard-bop (especially Monk). On Wednesday the 16th November, our last night at the Albion for a while, we heard six Monk tunes (plus tunes by Wes Montgomery, Lee Morgan, Joe Henderson and Sam Rivers).

Frank Gibson is a drummer of international repute, a sideman, educator and bandleader. While he is a versatile drummer, his predilection is for bebop and hard-bop (especially Monk). On Wednesday the 16th November, our last night at the Albion for a while, we heard six Monk tunes (plus tunes by Wes Montgomery, Lee Morgan, Joe Henderson and Sam Rivers). This is not a clone of the original Monk bands, but a modern quartet connected to the Monk vibe by musical lineage.

This is not a clone of the original Monk bands, but a modern quartet connected to the Monk vibe by musical lineage. There were familiar, much-loved Monk tunes and a few that are seldom heard such as ‘Light Blue’ and ‘Eronel’. Monk wrote around 70 compositions and they are instantly recognisable as being his. The angularity, quirky twists, the choppy rhythms, the lovely melodies and particular harmonic approach – a heady brew to gladden the heart of a devoted listener. We never tire of him or his interpreters. After Ellington, Monk compositions are the most recorded in Jazz. We remain faithful to his calling whether our tastes run to the avant-garde, swing or are firmly rooted in the mainstream. These tunes are among the essential buttresses holding up modern Jazz. They are open vehicles inviting endless and interesting explorations. They are a soundtrack to the Jazz life.

There were familiar, much-loved Monk tunes and a few that are seldom heard such as ‘Light Blue’ and ‘Eronel’. Monk wrote around 70 compositions and they are instantly recognisable as being his. The angularity, quirky twists, the choppy rhythms, the lovely melodies and particular harmonic approach – a heady brew to gladden the heart of a devoted listener. We never tire of him or his interpreters. After Ellington, Monk compositions are the most recorded in Jazz. We remain faithful to his calling whether our tastes run to the avant-garde, swing or are firmly rooted in the mainstream. These tunes are among the essential buttresses holding up modern Jazz. They are open vehicles inviting endless and interesting explorations. They are a soundtrack to the Jazz life.

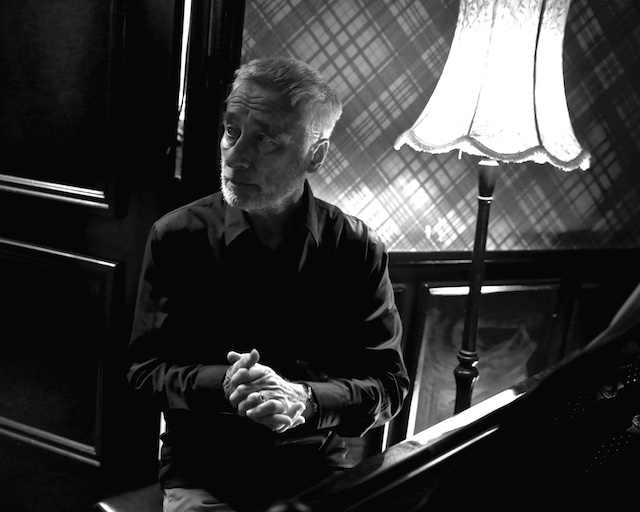

Au revoir is more than a simple good-bye. The fuller meaning is ‘until we meet again’. Jazz pianist, broadcaster and educator Phil Broadhurst is about to move to Paris, where he will reside for a few years (along with his partner vocalist/pianist Julie Mason). He assures us that he will return and it is not unreasonable to expect him to arrive back with new compositions and new projects to showcase. A Francophile (and francophone), Broadhurst has long been influenced by the writers and musicians of France. His last three albums ‘The dedication trilogy’ all contain strong references to that country. Wednesdays gig was centred on his recent output, but with new tunes and a surprise or two thrown in.

Au revoir is more than a simple good-bye. The fuller meaning is ‘until we meet again’. Jazz pianist, broadcaster and educator Phil Broadhurst is about to move to Paris, where he will reside for a few years (along with his partner vocalist/pianist Julie Mason). He assures us that he will return and it is not unreasonable to expect him to arrive back with new compositions and new projects to showcase. A Francophile (and francophone), Broadhurst has long been influenced by the writers and musicians of France. His last three albums ‘The dedication trilogy’ all contain strong references to that country. Wednesdays gig was centred on his recent output, but with new tunes and a surprise or two thrown in. Broadhurst is an institution on the New Zealand Jazz scene and it will feel strange with him absent. The strangeness on this particular Wednesday night was compounded by the impending American election result. An election dominated by bizarre outbursts of racism, belligerence, stupidity and misogyny. As the first number of the evening progressed, everyone relaxed; Broadhurst’s melodicism a balm for what ailed us. The tune was ‘Orange’ (a French commune in the Alps/Cote d’Azur region). Half way through the piece everyone’s mobiles lit up. I tried to ignore mine but the vibrating and flashing increased. I reached to shut it off and spotted the words – Trump wins US election. The ‘four horsemen of the apocalypse’ had just entered the room via electronic media. The tune ‘Orange’ is particularly beautiful (and I hope Broadhurst will forgive me for this association), but on this night, the title was also oddly appropriate. An orange gargoyle was about to release the furies upon a surprised world.

Broadhurst is an institution on the New Zealand Jazz scene and it will feel strange with him absent. The strangeness on this particular Wednesday night was compounded by the impending American election result. An election dominated by bizarre outbursts of racism, belligerence, stupidity and misogyny. As the first number of the evening progressed, everyone relaxed; Broadhurst’s melodicism a balm for what ailed us. The tune was ‘Orange’ (a French commune in the Alps/Cote d’Azur region). Half way through the piece everyone’s mobiles lit up. I tried to ignore mine but the vibrating and flashing increased. I reached to shut it off and spotted the words – Trump wins US election. The ‘four horsemen of the apocalypse’ had just entered the room via electronic media. The tune ‘Orange’ is particularly beautiful (and I hope Broadhurst will forgive me for this association), but on this night, the title was also oddly appropriate. An orange gargoyle was about to release the furies upon a surprised world. Accompanying Broadhurst were his regular quintet, Roger Manins (tenor), Mike Booth (trumpet), Oli Holland (bass) and Cam Sangster (drums – and with special guest Julie Mason (vocals). Broadhurst, and his various lineups have received numerous accolades. In recent years there have been nominations and awards; most recently the prestigious ‘Tui’ at the 2016 New Zealand Jazz Awards.

Accompanying Broadhurst were his regular quintet, Roger Manins (tenor), Mike Booth (trumpet), Oli Holland (bass) and Cam Sangster (drums – and with special guest Julie Mason (vocals). Broadhurst, and his various lineups have received numerous accolades. In recent years there have been nominations and awards; most recently the prestigious ‘Tui’ at the 2016 New Zealand Jazz Awards.  Anyone who follows NZ Jazz will be familiar with many of the tunes played on Wednesday; ‘Orange’, ‘Precious Metal’, ‘Loping’ etc. The nicest surprise of the evening was hearing a Frank Foster tune ‘Simone’ (absolutely nailed by Julie Mason). A fine tribute to Nina Simone, and appropriate to the night, given Simone’s views on the lamentable state of race relations in America. This unit is supremely polished and I highly recommend that you purchase the recent albums if you haven’t already done so. They are all still available from

Anyone who follows NZ Jazz will be familiar with many of the tunes played on Wednesday; ‘Orange’, ‘Precious Metal’, ‘Loping’ etc. The nicest surprise of the evening was hearing a Frank Foster tune ‘Simone’ (absolutely nailed by Julie Mason). A fine tribute to Nina Simone, and appropriate to the night, given Simone’s views on the lamentable state of race relations in America. This unit is supremely polished and I highly recommend that you purchase the recent albums if you haven’t already done so. They are all still available from

Every time an article appeared in the late twentieth century proclaiming the death of Modernism, another appeared shortly after; pointing out, rightly, that profound echoes of the movement will linger and intrigue a while yet. Perhaps because of when I was born, (immediately after the second war), this movement fascinates me and will until my last breath. It was a profound moment in the human journey when the hegemony of historical artistic values were challenged, discarded. Schoenberg, Coltrane, Brubeck, Riley, Colman, Matisse, Picasso, Miro. Pollock, Rothko, Eliot, Pound, Kerouac, and even Freud are defined by this impulse to move free from the received wisdom of history.

Every time an article appeared in the late twentieth century proclaiming the death of Modernism, another appeared shortly after; pointing out, rightly, that profound echoes of the movement will linger and intrigue a while yet. Perhaps because of when I was born, (immediately after the second war), this movement fascinates me and will until my last breath. It was a profound moment in the human journey when the hegemony of historical artistic values were challenged, discarded. Schoenberg, Coltrane, Brubeck, Riley, Colman, Matisse, Picasso, Miro. Pollock, Rothko, Eliot, Pound, Kerouac, and even Freud are defined by this impulse to move free from the received wisdom of history. Stephen Small is a wonderful pianist but he is much more than that. He conjures up musical projects that catch people unawares; original projects, affording us a viewpoint on life and art that we would not experience otherwise. The concept behind the first outing of the Mexico City Blues band was to look at, examine the Jazz of 1957, fusing it with the Beat poems of Jack Kerouac (Kerouac wrote Mexico City Blues in that year – see earlier post). This was in part a re-imagining, but also a fresh look through post millennial eyes. When Stephen Small takes on a project he brings to it an immense musical knowledge, but more importantly an eye for the unusual, for quirky detail (no artist, musician, writer or poet worth their salt can succeed without this). When artists do their job well they show us the world afresh.

Stephen Small is a wonderful pianist but he is much more than that. He conjures up musical projects that catch people unawares; original projects, affording us a viewpoint on life and art that we would not experience otherwise. The concept behind the first outing of the Mexico City Blues band was to look at, examine the Jazz of 1957, fusing it with the Beat poems of Jack Kerouac (Kerouac wrote Mexico City Blues in that year – see earlier post). This was in part a re-imagining, but also a fresh look through post millennial eyes. When Stephen Small takes on a project he brings to it an immense musical knowledge, but more importantly an eye for the unusual, for quirky detail (no artist, musician, writer or poet worth their salt can succeed without this). When artists do their job well they show us the world afresh.

The second set was free improvised music in the tradition of, and honouring the all but forgotten experimental improvisers of 1960’s Russia. For this set Small was joined by Dave Chechelashvili on modular synthesiser. As Small carved out motifs and themes, developing them and exploring the possibilities, Chechelashvili shaped the sound. Small’s Korg keyboard was split and connected with the modular synth; as patch cords were adjusted and knobs tweaked, we heard a music that you don’t expect from Communist Russia. Evidently and surprisingly, this was tolerated because it was perceived as artistic exploration. It was hard not to think of Glass, Reich or Riley and wonder at this parallel development.

The second set was free improvised music in the tradition of, and honouring the all but forgotten experimental improvisers of 1960’s Russia. For this set Small was joined by Dave Chechelashvili on modular synthesiser. As Small carved out motifs and themes, developing them and exploring the possibilities, Chechelashvili shaped the sound. Small’s Korg keyboard was split and connected with the modular synth; as patch cords were adjusted and knobs tweaked, we heard a music that you don’t expect from Communist Russia. Evidently and surprisingly, this was tolerated because it was perceived as artistic exploration. It was hard not to think of Glass, Reich or Riley and wonder at this parallel development.

I was always going to love Amsterdam and it didn’t disappoint. The city has long been associated with the arts and with quality improvised music. It is a mature, liberal city comfortable in its skin, a place where you can legally purchase honey-cured Moroccan Hash in coffee bars, visit astonishing art galleries or enjoy good music at Jazz clubs like the Bimhuis. It is a city like few others, a truly happy place moving at its own pace. In spite of its laid back feel, the unhurried chaos, there is an underlying work ethic that makes everything run like clockwork. Like Venice it is a maze of pretty canals. Unlike Venice, the main source of transportation is the bicycle. An incalculable number pass you as you walk the canals, they even have their own multi-story parking buildings.

I was always going to love Amsterdam and it didn’t disappoint. The city has long been associated with the arts and with quality improvised music. It is a mature, liberal city comfortable in its skin, a place where you can legally purchase honey-cured Moroccan Hash in coffee bars, visit astonishing art galleries or enjoy good music at Jazz clubs like the Bimhuis. It is a city like few others, a truly happy place moving at its own pace. In spite of its laid back feel, the unhurried chaos, there is an underlying work ethic that makes everything run like clockwork. Like Venice it is a maze of pretty canals. Unlike Venice, the main source of transportation is the bicycle. An incalculable number pass you as you walk the canals, they even have their own multi-story parking buildings.

The Bimhuis (or Bim as it is affectionately known) is an amazing venue, acoustically perfect; with seating sloping towards the stage and clear sight lines. It seats about 150 people and has an excellent restaurant attached. From the restaurant you can see the busy harbour, from the auditorium you can see intercity trains passing below. The Bim has its own online radio station and is set up for high quality recording. If you’re ever near Amsterdam, you’d be crazy not to treat yourself to a to meal and music there.

The Bimhuis (or Bim as it is affectionately known) is an amazing venue, acoustically perfect; with seating sloping towards the stage and clear sight lines. It seats about 150 people and has an excellent restaurant attached. From the restaurant you can see the busy harbour, from the auditorium you can see intercity trains passing below. The Bim has its own online radio station and is set up for high quality recording. If you’re ever near Amsterdam, you’d be crazy not to treat yourself to a to meal and music there.

From early in the first set, I felt the passion behind the performances, the sheer exuberance that is generated when a group know that they are performing effectively. Seasoned touring musicians sometimes sacrifice this – perhaps the effort of being on the road, the effects of jet lag, robbing them of warmth. It reinforces my view as a listener, that an artist needs more than chops to fully engage with an audience. When a band is comfortable on stage, properly rehearsed and above all up for a riotous night, magic can happen.

From early in the first set, I felt the passion behind the performances, the sheer exuberance that is generated when a group know that they are performing effectively. Seasoned touring musicians sometimes sacrifice this – perhaps the effort of being on the road, the effects of jet lag, robbing them of warmth. It reinforces my view as a listener, that an artist needs more than chops to fully engage with an audience. When a band is comfortable on stage, properly rehearsed and above all up for a riotous night, magic can happen. Trumpeter Finn Scholes can always surprise and over recent years he has impressed me increasingly. His vibrantly brassy ‘south of the border’ sound in the Carnivorous Plant Society is well-known, but anyone who thought that was all there was to him, hasn’t been paying due attention. He is raw and raspy on avant-garde gigs, mellow and moody on vibes and in this lineup reminiscent of the young Freddie Hubbard. His solo’s had bite and narrative, his ensemble playing was tight; above all, he generated palpable excitement, the sort that brings people back to live music again and again.

Trumpeter Finn Scholes can always surprise and over recent years he has impressed me increasingly. His vibrantly brassy ‘south of the border’ sound in the Carnivorous Plant Society is well-known, but anyone who thought that was all there was to him, hasn’t been paying due attention. He is raw and raspy on avant-garde gigs, mellow and moody on vibes and in this lineup reminiscent of the young Freddie Hubbard. His solo’s had bite and narrative, his ensemble playing was tight; above all, he generated palpable excitement, the sort that brings people back to live music again and again.

Dan Bolton is an Australian born, New York based musician, at present touring New Zealand. His first show was at the CJC (Creative Jazz Club) in Auckland. While singer, songwriters who accompany themselves on piano, are a firmly established tradition in Jazz, we see them on tour very rarely. Many Jazz vocalists (like Ella Fitzgerald) could accompany themselves well, but few choose to do so. A number of notable musicians mastered this skill, notably Nat Cole, Ray Charles, and Shirley Horn. Doing two jobs simultaneously is always harder than doing one and especially where vocals and piano are concerned. The energies and postures require careful coordination and I suspect that this is harder than accompanying yourself on guitar.

Dan Bolton is an Australian born, New York based musician, at present touring New Zealand. His first show was at the CJC (Creative Jazz Club) in Auckland. While singer, songwriters who accompany themselves on piano, are a firmly established tradition in Jazz, we see them on tour very rarely. Many Jazz vocalists (like Ella Fitzgerald) could accompany themselves well, but few choose to do so. A number of notable musicians mastered this skill, notably Nat Cole, Ray Charles, and Shirley Horn. Doing two jobs simultaneously is always harder than doing one and especially where vocals and piano are concerned. The energies and postures require careful coordination and I suspect that this is harder than accompanying yourself on guitar. Bolton is unusual in that he composes tunes which feel modern, but in a style reminiscent of the Great American Songbook; many of his tunes, are not dissimilar from those which came out of Tin Pan Alley, having the vibe of Irving Berlin or Cole Porter. The melodies are catchy in a time honoured way and the lyrics often biting; sometimes capturing our post-millennial angst. Many of Bolton’s tunes centre on the age-old themes of love and loss, others sarcastically critique modern American life. All maintain their sense of originality, in spite of the above comparisons.

Bolton is unusual in that he composes tunes which feel modern, but in a style reminiscent of the Great American Songbook; many of his tunes, are not dissimilar from those which came out of Tin Pan Alley, having the vibe of Irving Berlin or Cole Porter. The melodies are catchy in a time honoured way and the lyrics often biting; sometimes capturing our post-millennial angst. Many of Bolton’s tunes centre on the age-old themes of love and loss, others sarcastically critique modern American life. All maintain their sense of originality, in spite of the above comparisons. Travelling with Bolton is the perennially popular drummer Mark Lockett. Lockett, like Bolton, lives in New York, but for several months of each year, he travels as band-leader, (or as hired gun as in this case). Lockett was born in New Zealand and he always gets a welcome reception when he makes it back. Watch out on gig noticeboards for him. He has another tour coming up shortly and this time with an organ trio. On tenor saxophone and flute was Auckland’s Roger Manins, his swoon-worthy ballad chops manifesting in their full glory. Mostyn Cole featured on upright bass, a regular at the CJC and an able musician. We heard some tantalising snippets of arco bass from him – more of that, please.

Travelling with Bolton is the perennially popular drummer Mark Lockett. Lockett, like Bolton, lives in New York, but for several months of each year, he travels as band-leader, (or as hired gun as in this case). Lockett was born in New Zealand and he always gets a welcome reception when he makes it back. Watch out on gig noticeboards for him. He has another tour coming up shortly and this time with an organ trio. On tenor saxophone and flute was Auckland’s Roger Manins, his swoon-worthy ballad chops manifesting in their full glory. Mostyn Cole featured on upright bass, a regular at the CJC and an able musician. We heard some tantalising snippets of arco bass from him – more of that, please.

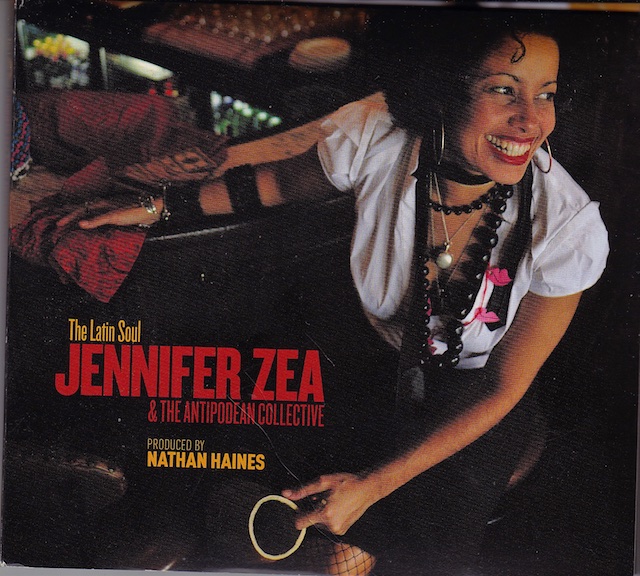

Last Wednesday saw the Venezuelan-born vocalist Jennifer Zea performing at the CJC. Her appearance was long overdue, the audience enthusiastic in anticipation of spicy South American Rhythms and the warm tones of the Spanish language in song form. When you look at where Venezuela sits on the map, you learn a lot about its music. Located in the northeast of South America, bordered by the Caribbean and by Brazil, positioned on a unique musical axis. Music blithely ignores the artificial barriers imposed by cartographers and politicians. Even Trump’s insulting wall could never be built high enough to stem musical cross-pollination. Music goes where people go, and remains as an echo long after they have moved on. Jennifer Zea is an embodiment of her country’s music; folk traditions, newer forms (Jaropo), Jazz, Soul, Bossa influences from Brazil and a pinch of Mambo, Salsa or Merengue.

Last Wednesday saw the Venezuelan-born vocalist Jennifer Zea performing at the CJC. Her appearance was long overdue, the audience enthusiastic in anticipation of spicy South American Rhythms and the warm tones of the Spanish language in song form. When you look at where Venezuela sits on the map, you learn a lot about its music. Located in the northeast of South America, bordered by the Caribbean and by Brazil, positioned on a unique musical axis. Music blithely ignores the artificial barriers imposed by cartographers and politicians. Even Trump’s insulting wall could never be built high enough to stem musical cross-pollination. Music goes where people go, and remains as an echo long after they have moved on. Jennifer Zea is an embodiment of her country’s music; folk traditions, newer forms (Jaropo), Jazz, Soul, Bossa influences from Brazil and a pinch of Mambo, Salsa or Merengue. The Caribbean region is the prime example of musical cross-pollination; rhythms and melodies, vocal forms and hybrid harmonization, a constant evolution into new and vibrant forms while updating and preserving the discrete pockets of older folk music styles. A weighty tome titled ‘Music and the Latin American Culture – Regional Traditions’ makes two observations; the music of the Venezuelan region is mostly hot or vibrant (see the definition of Salsa) and there is a strong underlying tradition of shamanism (manifest in musical form). The hypnotic rhythms and chants remain largely intact according to Schecter. With percussionist, Miguel Fuentes backing her, Zea conveyed the compellingly hypnotic soulful quality of her traditional music to good effect.

The Caribbean region is the prime example of musical cross-pollination; rhythms and melodies, vocal forms and hybrid harmonization, a constant evolution into new and vibrant forms while updating and preserving the discrete pockets of older folk music styles. A weighty tome titled ‘Music and the Latin American Culture – Regional Traditions’ makes two observations; the music of the Venezuelan region is mostly hot or vibrant (see the definition of Salsa) and there is a strong underlying tradition of shamanism (manifest in musical form). The hypnotic rhythms and chants remain largely intact according to Schecter. With percussionist, Miguel Fuentes backing her, Zea conveyed the compellingly hypnotic soulful quality of her traditional music to good effect.  Fuentes was born in the USA but grew up in Puerto Rico. These days like Zea, he lives in Auckland. Music like this demands high-quality authentic latin percussion and that’s exactly what happened. Traps drums were not needed here. Regular Zea accompanist, Jazz Pianist Kevin Field was also in the lineup. Field plays in many contexts and his accompanist credentials are second to none. He has regularly worked with Zea and (like Fuentes) most notably on her lovely 2012 release ‘The Latin Soul’. If you have a love of Cubano or Caribean style music, grab a copy of this album. Even on straight-ahead gigs, I have heard Field sneak in tasty clave rhythms. If you want to hear cross-rhythms at their best – skillfully woven by Field and Fuentes, it is on this album. An added incentive are the compositions, mostly by Field and Zea (and Jonathan Crayford). On upright bass for this gig was Mostyn Cole, an experienced bassist now residing in the Auckland region.

Fuentes was born in the USA but grew up in Puerto Rico. These days like Zea, he lives in Auckland. Music like this demands high-quality authentic latin percussion and that’s exactly what happened. Traps drums were not needed here. Regular Zea accompanist, Jazz Pianist Kevin Field was also in the lineup. Field plays in many contexts and his accompanist credentials are second to none. He has regularly worked with Zea and (like Fuentes) most notably on her lovely 2012 release ‘The Latin Soul’. If you have a love of Cubano or Caribean style music, grab a copy of this album. Even on straight-ahead gigs, I have heard Field sneak in tasty clave rhythms. If you want to hear cross-rhythms at their best – skillfully woven by Field and Fuentes, it is on this album. An added incentive are the compositions, mostly by Field and Zea (and Jonathan Crayford). On upright bass for this gig was Mostyn Cole, an experienced bassist now residing in the Auckland region. The gig featured some Zea compositions, three standards and to my delight some authentic Bossa. The Bossa tunes were mostly by the Brazilian genius Tom Jobim and sung in Portuguese (which is not her native language). Although Portuguese is the most commonly spoken language in Latin America, it is only the main spoken language of one country, Brazil. To learn Bossa she spent time with a teacher in order to understand the nuances and deep meanings. While respecting the Bossa song form she had the confidence to bring the music closer to her own Venezuelan musical traditions. Even her intonation was redolent of her region, unmistakably Hispanic South American.

The gig featured some Zea compositions, three standards and to my delight some authentic Bossa. The Bossa tunes were mostly by the Brazilian genius Tom Jobim and sung in Portuguese (which is not her native language). Although Portuguese is the most commonly spoken language in Latin America, it is only the main spoken language of one country, Brazil. To learn Bossa she spent time with a teacher in order to understand the nuances and deep meanings. While respecting the Bossa song form she had the confidence to bring the music closer to her own Venezuelan musical traditions. Even her intonation was redolent of her region, unmistakably Hispanic South American.

Mooga Fooga are well travelled, and as they move about they carve deep grooves into the sonic landscape. Their music is deliberately genre blending, with funk, rock, soul and Jazz shuffled together. Their music is often loud but they can play in a muted voice. While all of those influences are unambiguously in the mix, based on what I saw on Wednesday, they can tilt the emphasis any way they choose. This eclecticism is not the result of a random amalgam, but a clever fusing of the base metals underpinning the genres. In some of their online clips they are reminiscent of groups like Cream (albeit funked up), but on this gig, their Jazz Funk roots were most in evidence. I suspect that saxophonist Kushal Talele was the compass in that regard.

Mooga Fooga are well travelled, and as they move about they carve deep grooves into the sonic landscape. Their music is deliberately genre blending, with funk, rock, soul and Jazz shuffled together. Their music is often loud but they can play in a muted voice. While all of those influences are unambiguously in the mix, based on what I saw on Wednesday, they can tilt the emphasis any way they choose. This eclecticism is not the result of a random amalgam, but a clever fusing of the base metals underpinning the genres. In some of their online clips they are reminiscent of groups like Cream (albeit funked up), but on this gig, their Jazz Funk roots were most in evidence. I suspect that saxophonist Kushal Talele was the compass in that regard. Years ago I picked up a guitar trio album featuring Bareli Lagrene, Jaco Pistorius, and a European drummer (I can’t recall his name). I marveled at the seamless blending of styles, as they performed Hendrix and Shorter with equal integrity, paying due respect to each. This music has a heavier funk element; Jazz funk with a little touch of metal and the occasional the choppy lines of Monk thrown in. Apart from their punchy lines and the exchanges during the head, there was room for improvisation as the tunes developed.

Years ago I picked up a guitar trio album featuring Bareli Lagrene, Jaco Pistorius, and a European drummer (I can’t recall his name). I marveled at the seamless blending of styles, as they performed Hendrix and Shorter with equal integrity, paying due respect to each. This music has a heavier funk element; Jazz funk with a little touch of metal and the occasional the choppy lines of Monk thrown in. Apart from their punchy lines and the exchanges during the head, there was room for improvisation as the tunes developed. I am familiar with Kushal Talele, Adam Tobeck and Joel Shadbolt as I have encountered them all before. Each in different situations to what was on offer last night. Talele has a distinct post-Coltrane sound and is very much in the camp of the New York modernist tenor players. He returned last year from overseas and played a gig at the CJC. Sadly, we are to lose him again as he heads to New York for a few years. Tobeck is versatile and notable for his tightly focused groove beats. He was essential to this lineup and this band was a natural fit for him. I have seen Shadbolt less often but I enjoyed his loud bluesy funk at the 2015 Tauranga Jazz festival. He is a crowd pleaser and looks every inch the part as he pumps out his ear-pleasing lines and phrases. While I had not previously heard electric bassist Rory Macartney, he is well-respected about town. There is a real bite to his playing, a bite that is perfect for a lineup like this.

I am familiar with Kushal Talele, Adam Tobeck and Joel Shadbolt as I have encountered them all before. Each in different situations to what was on offer last night. Talele has a distinct post-Coltrane sound and is very much in the camp of the New York modernist tenor players. He returned last year from overseas and played a gig at the CJC. Sadly, we are to lose him again as he heads to New York for a few years. Tobeck is versatile and notable for his tightly focused groove beats. He was essential to this lineup and this band was a natural fit for him. I have seen Shadbolt less often but I enjoyed his loud bluesy funk at the 2015 Tauranga Jazz festival. He is a crowd pleaser and looks every inch the part as he pumps out his ear-pleasing lines and phrases. While I had not previously heard electric bassist Rory Macartney, he is well-respected about town. There is a real bite to his playing, a bite that is perfect for a lineup like this. The tunes were seldom given titles and I suspect that most were originals. Details like that don’t matter on a gig like this – it is about the groove. I gained the impression that the three regulars, Macartney, Shadbolt and Talele all contributed compositions and arrangements. There are some good YouTube clips up from this group and I have added one more from this gig.

The tunes were seldom given titles and I suspect that most were originals. Details like that don’t matter on a gig like this – it is about the groove. I gained the impression that the three regulars, Macartney, Shadbolt and Talele all contributed compositions and arrangements. There are some good YouTube clips up from this group and I have added one more from this gig.

Kevin Field has for many years been regarded as a phenomenon on the New Zealand Jazz scene. A gifted pianist and composer whose approach to composition and harmony is strikingly original. When you listen to many pianists you can hear their influences, discern the pathways that led them to where they are. With Field, those influences are less obvious. I suspect that this independence, originality, makes it easier for him to strike out in any direction of his choosing. On his ‘Field of Vision’ album, he moved into uncrowded space, one occupied by very few Jazz pianists. It was Jazz without compromise but utilising grooves, rhythms, and melodies of other genres. The music contained distinct echoes of the disco/Jazz/funk era, crafting it carefully and forging a new post-millennial sound.

Kevin Field has for many years been regarded as a phenomenon on the New Zealand Jazz scene. A gifted pianist and composer whose approach to composition and harmony is strikingly original. When you listen to many pianists you can hear their influences, discern the pathways that led them to where they are. With Field, those influences are less obvious. I suspect that this independence, originality, makes it easier for him to strike out in any direction of his choosing. On his ‘Field of Vision’ album, he moved into uncrowded space, one occupied by very few Jazz pianists. It was Jazz without compromise but utilising grooves, rhythms, and melodies of other genres. The music contained distinct echoes of the disco/Jazz/funk era, crafting it carefully and forging a new post-millennial sound. The tunes were all memorable and within a few listenings, you could hum the themes. This is not so common in modern Jazz and less so with music (like Fields) which retains its Jazz complexity. In Fields case, the clean melodic hooks do not come at the expense of harmonic invention. That is a tricky balancing act and one he achieves convincingly. His co-leadership of ‘DOG’ took him in a different direction again, but the same deftly crafted grooves astounded us. His recent album ‘The A-List’, was a further excursion into the disco/Jazz/funk realm. It is slightly tongue in cheek while still challenging the listener to think outside the square. Artists like this take the music forward, it is up to us to catch up.

The tunes were all memorable and within a few listenings, you could hum the themes. This is not so common in modern Jazz and less so with music (like Fields) which retains its Jazz complexity. In Fields case, the clean melodic hooks do not come at the expense of harmonic invention. That is a tricky balancing act and one he achieves convincingly. His co-leadership of ‘DOG’ took him in a different direction again, but the same deftly crafted grooves astounded us. His recent album ‘The A-List’, was a further excursion into the disco/Jazz/funk realm. It is slightly tongue in cheek while still challenging the listener to think outside the square. Artists like this take the music forward, it is up to us to catch up. They played at the Wellington Jazz festival recently and for many Wellingtonians, this was their first exposure to the group. I saw that show and I immediately noticed how the familiar tunes had subtly changed. ‘Perfect Disco’ with its energised danceable funk momentum was recast as a duo piece. Field and vocalist Chaperon wowed them with that number. We also heard this duo version last week. Other familiar tunes had developed into profoundly interactive exchanges. The sort that can only occur between highly attuned musicians. This is where the guitar mastery and the deep listening of Nacey came into its own. His Godin guitar soaring with stunning clarity while Field reacted in kind, urging them further out with each challenge.

They played at the Wellington Jazz festival recently and for many Wellingtonians, this was their first exposure to the group. I saw that show and I immediately noticed how the familiar tunes had subtly changed. ‘Perfect Disco’ with its energised danceable funk momentum was recast as a duo piece. Field and vocalist Chaperon wowed them with that number. We also heard this duo version last week. Other familiar tunes had developed into profoundly interactive exchanges. The sort that can only occur between highly attuned musicians. This is where the guitar mastery and the deep listening of Nacey came into its own. His Godin guitar soaring with stunning clarity while Field reacted in kind, urging them further out with each challenge. Again we see Thomas and McArthur doing what they do best. Working hard and rising to the challenge. Thomas laying down the tricky rhythms and while McArthur runs his bass lines. While pleasant to the ear, there is not doubt at all that these compositions required skill and concentration. It is on gigs like this that the musicians familiarity with the material and each other pays dividends. It was also nice to hear Chaperon on some new and old material. She is a real crowd pleaser – she looks great on stage and sings up a storm.

Again we see Thomas and McArthur doing what they do best. Working hard and rising to the challenge. Thomas laying down the tricky rhythms and while McArthur runs his bass lines. While pleasant to the ear, there is not doubt at all that these compositions required skill and concentration. It is on gigs like this that the musicians familiarity with the material and each other pays dividends. It was also nice to hear Chaperon on some new and old material. She is a real crowd pleaser – she looks great on stage and sings up a storm. I can’t remember when I first became conscious of Polish Jazz, but after Tomasz Stanko, Poland was forever on my listening radar. After that, I would listen to Polish improvisers whenever I came across them, Wasilewski, Komeda etc, and all the more so when I discovered later in life that I was a quarter Polish. In light of the above, I was naturally interested when I came across an Auckland-based, Polish-born pianist Michal Martyniuk. He was standing in for Kevin Field at a Nathan Haines gig – around the time of “The Poets Embrace’ release. Since then I have seen him with various iterations of Haines’ bands but until last week, never at a gig where he was the leader.

I can’t remember when I first became conscious of Polish Jazz, but after Tomasz Stanko, Poland was forever on my listening radar. After that, I would listen to Polish improvisers whenever I came across them, Wasilewski, Komeda etc, and all the more so when I discovered later in life that I was a quarter Polish. In light of the above, I was naturally interested when I came across an Auckland-based, Polish-born pianist Michal Martyniuk. He was standing in for Kevin Field at a Nathan Haines gig – around the time of “The Poets Embrace’ release. Since then I have seen him with various iterations of Haines’ bands but until last week, never at a gig where he was the leader.  It is an oft-debated topic, but I sometimes hear references to time and place in original music. After hearing Martyniuk I could identify his northern European influences. When I asked the pianist about the artists he most admires, he quickly identified Lyle Mays and Pat Metheny (also Weather Report plus Miles and Herbie). The Metheny/Mays reference is definitely evident but sifted through a Eurocentric filter. Mays, although influenced by Evans never sounded like a typical American pianist. Martyniuk’s compositions and performance contain all of the hallmarks of modern Euro jazz, a sound I hear in the Alboran Trio, Wasilewski and younger pianists like Michal Tokaj. A warmer sound than the Scandinavian pianists but as light filled and airy. There is a beauty to Martyiuk’s playing, a stylistic identity. For such a young pianist to have located this special sound is impressive.

It is an oft-debated topic, but I sometimes hear references to time and place in original music. After hearing Martyniuk I could identify his northern European influences. When I asked the pianist about the artists he most admires, he quickly identified Lyle Mays and Pat Metheny (also Weather Report plus Miles and Herbie). The Metheny/Mays reference is definitely evident but sifted through a Eurocentric filter. Mays, although influenced by Evans never sounded like a typical American pianist. Martyniuk’s compositions and performance contain all of the hallmarks of modern Euro jazz, a sound I hear in the Alboran Trio, Wasilewski and younger pianists like Michal Tokaj. A warmer sound than the Scandinavian pianists but as light filled and airy. There is a beauty to Martyiuk’s playing, a stylistic identity. For such a young pianist to have located this special sound is impressive. Something that many post-millennial Jazz musicians avoid, is evoking a sense of beauty. I can understand that because it must be done well or not at all. It is the territory of balladeers like Ben Webster and the territory of artists like Metheny. This was done well. The compositions were cleverly constructed around developing themes and with nothing was rushed, allowing melodic inventions to manifest. The tunes were also cleverly modulated, subtly amping up the tension to good effect at key points. Like Bennie Lackner, he used electronic keyboards to enhance or emphasize a phrase, but very sparingly.

Something that many post-millennial Jazz musicians avoid, is evoking a sense of beauty. I can understand that because it must be done well or not at all. It is the territory of balladeers like Ben Webster and the territory of artists like Metheny. This was done well. The compositions were cleverly constructed around developing themes and with nothing was rushed, allowing melodic inventions to manifest. The tunes were also cleverly modulated, subtly amping up the tension to good effect at key points. Like Bennie Lackner, he used electronic keyboards to enhance or emphasize a phrase, but very sparingly. Again we see a musician deploying a top rated rhythm section to good advantage. With McArthur and Samsom behind him, he again showed wisdom. He worked with them and they gave him plenty in return. Although we often see this particular bass player and drummer in diverse situations, they appeared very comfortable here. The overall effect was that of interplay and cohesion.

Again we see a musician deploying a top rated rhythm section to good advantage. With McArthur and Samsom behind him, he again showed wisdom. He worked with them and they gave him plenty in return. Although we often see this particular bass player and drummer in diverse situations, they appeared very comfortable here. The overall effect was that of interplay and cohesion. Martyniuk came to New Zealand around ten years ago and he attended the Auckland School of Music. Along with producer Nick Williams, he is soon to release a Jazz infused Soul album which will feature internationally renowned artists like Kevin Mark Trail, Nathan Haines, Miguel Fuentes and others. Judging by the huge audience at this gig his future looks very rosy indeed. The Jazz club turned away dozens of attendees in the end. A good problem to have.

Martyniuk came to New Zealand around ten years ago and he attended the Auckland School of Music. Along with producer Nick Williams, he is soon to release a Jazz infused Soul album which will feature internationally renowned artists like Kevin Mark Trail, Nathan Haines, Miguel Fuentes and others. Judging by the huge audience at this gig his future looks very rosy indeed. The Jazz club turned away dozens of attendees in the end. A good problem to have.  When I started attending the CJC, I heard Peter Koopman quite often. He was always impressive, but never a showy guitarist. His approach matched his quiet demeanor, an easy-going manner obscuring a real determination to excel at his craft. Before long he moved to Sydney and although the local Jazz scene laments this musicians rite of passage, we also know it is the right thing. At best, these offshore journeys produce the Mike Nocks and the Matt Penmans, and we all benefit from that.

When I started attending the CJC, I heard Peter Koopman quite often. He was always impressive, but never a showy guitarist. His approach matched his quiet demeanor, an easy-going manner obscuring a real determination to excel at his craft. Before long he moved to Sydney and although the local Jazz scene laments this musicians rite of passage, we also know it is the right thing. At best, these offshore journeys produce the Mike Nocks and the Matt Penmans, and we all benefit from that. We have seen him back in New Zealand a few times during the last five years, but this is his first visit leading a guitar trio. As anticipated, we experienced a more mature Koopman, his guitar work showcasing well-honed skills. Australia is a merciless testing ground for improvising musicians and especially so for guitarists. Working in the same scene as Carl Dewhurst or James Muller, and holding your own, the proof of the pudding. In 2014 Koopman was placed 3rd in the Australian National Jazz Awards, which are held at Wangaratta each year. These awards are fiercely contested and that is no small accomplishment.

We have seen him back in New Zealand a few times during the last five years, but this is his first visit leading a guitar trio. As anticipated, we experienced a more mature Koopman, his guitar work showcasing well-honed skills. Australia is a merciless testing ground for improvising musicians and especially so for guitarists. Working in the same scene as Carl Dewhurst or James Muller, and holding your own, the proof of the pudding. In 2014 Koopman was placed 3rd in the Australian National Jazz Awards, which are held at Wangaratta each year. These awards are fiercely contested and that is no small accomplishment.  The Inner Westies Trio for the New Zealand trip was Peter Koopman (guitar), Max Alduca (bass) and Stephen Thomas (drums). The guitarist and Bass player from West Sydney, the drummer from West Auckland. Alduca is a compelling bass player, and a drawcard on his own. He often includes a touch of tasteful arco bass in his performance. I last saw him when he toured with the ‘Antipodeans’, an innovative young ensemble, populated with musicians from three countries. Alduca made a hit then and reinforced our positive view of him this night. He has a number of gigs about Auckland aside from the CJC gig. A player bursting with originality and with a notable way of engaging with audiences. Nice to see him back and especially in this company.

The Inner Westies Trio for the New Zealand trip was Peter Koopman (guitar), Max Alduca (bass) and Stephen Thomas (drums). The guitarist and Bass player from West Sydney, the drummer from West Auckland. Alduca is a compelling bass player, and a drawcard on his own. He often includes a touch of tasteful arco bass in his performance. I last saw him when he toured with the ‘Antipodeans’, an innovative young ensemble, populated with musicians from three countries. Alduca made a hit then and reinforced our positive view of him this night. He has a number of gigs about Auckland aside from the CJC gig. A player bursting with originality and with a notable way of engaging with audiences. Nice to see him back and especially in this company.

The Joni Mitchell/ Charles Mingus project is always ripe for reevaluation and I’m glad that Caro Manins was the one to explore it again. The connection between Joni and Jazz experimentalism runs deep. Rolling Stone Magazine figured it out early on, describing her as a ‘Jazz savvy experimentalist’. While the connection is obvious in her 1979 ‘Mingus’ album the move toward a freer music and towards harmonic and rhythmic complexity began earlier in the mid 70’s. Initially coming up through the American folk tradition, she gradually embraced a different style. She would later say, “Anyone could have written my earlier music, but Hejira (and later albums) could only have come from me”. From the 70’s on, she utilised her own guitar tunings and often incorporated pedal point, chromaticism, and modality in her compositions. If you look at her later musical collaborations, names like Jaco Pastorius, Herbie Hancock, and Wayne Shorter stand out.

The Joni Mitchell/ Charles Mingus project is always ripe for reevaluation and I’m glad that Caro Manins was the one to explore it again. The connection between Joni and Jazz experimentalism runs deep. Rolling Stone Magazine figured it out early on, describing her as a ‘Jazz savvy experimentalist’. While the connection is obvious in her 1979 ‘Mingus’ album the move toward a freer music and towards harmonic and rhythmic complexity began earlier in the mid 70’s. Initially coming up through the American folk tradition, she gradually embraced a different style. She would later say, “Anyone could have written my earlier music, but Hejira (and later albums) could only have come from me”. From the 70’s on, she utilised her own guitar tunings and often incorporated pedal point, chromaticism, and modality in her compositions. If you look at her later musical collaborations, names like Jaco Pastorius, Herbie Hancock, and Wayne Shorter stand out. To her amazement at the time, a dying Charles Mingus asked Joni to call by. He told her that he had written a number of songs for her. Mingus passed before the completion of her project, but he heard all of the tunes except ‘God must be a Bogey Man’. Her ‘Mingus’ album followed soon after. “It was as if I had been standing by a river – one toe in the water. Charles came along and pushed me in – sink or swim”.

To her amazement at the time, a dying Charles Mingus asked Joni to call by. He told her that he had written a number of songs for her. Mingus passed before the completion of her project, but he heard all of the tunes except ‘God must be a Bogey Man’. Her ‘Mingus’ album followed soon after. “It was as if I had been standing by a river – one toe in the water. Charles came along and pushed me in – sink or swim”. The project deserved a good lineup and it got one. Caro Manins, Roger Manins, Jonathan Crayford, Cameron McArthur and Ron Samsom. Crayford was especially interesting on this gig. His abstract explorative adventuring replaced by rich traditional voicings – his solos a history lesson; from locked hands chord-work to impressionistic delicacy. All of the musicians were respectful of Joni’s body of work and they understood that the best way to honour her legacy was by interpreting her work honestly and imaginatively. Not every tune came from Joni’s ‘Mingus’ album but all followed the Joni/Mingus/Jazz theme.

The project deserved a good lineup and it got one. Caro Manins, Roger Manins, Jonathan Crayford, Cameron McArthur and Ron Samsom. Crayford was especially interesting on this gig. His abstract explorative adventuring replaced by rich traditional voicings – his solos a history lesson; from locked hands chord-work to impressionistic delicacy. All of the musicians were respectful of Joni’s body of work and they understood that the best way to honour her legacy was by interpreting her work honestly and imaginatively. Not every tune came from Joni’s ‘Mingus’ album but all followed the Joni/Mingus/Jazz theme. The gig was very well attended (no surprise there) and the audience enthusiastic. This was a CJC (Creative Jazz Club) event and it took place at the Albion Hotel on 29th June 2016. Caro Manins (leader, arranger, vocals), Jonathan Crayford (piano), Roger Manins (tenor saxophone), Cameron McArthur (Bass), Ron Samsom (drums, percussion).

The gig was very well attended (no surprise there) and the audience enthusiastic. This was a CJC (Creative Jazz Club) event and it took place at the Albion Hotel on 29th June 2016. Caro Manins (leader, arranger, vocals), Jonathan Crayford (piano), Roger Manins (tenor saxophone), Cameron McArthur (Bass), Ron Samsom (drums, percussion).

To the best of my knowledge, Jonathan Besser has not played at the CJC (Creative Jazz Club) before. While he is best known as an important composer for The New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, The New Zealand String Quartet and The Royal New Zealand Ballet, he is also a significant leader of small ensembles. Ensembles which venture far into the territory of experimental, electronic and improvised music. It is impossible to separate the man from his music. It is eclectic, original and often plaintive but generally with a sly twist of humour thrown in. In spite of his standing in the music world, Besser is modest. At the CJC he was happy to lead from the piano, which was in partial darkness and at the rear of the ensemble. His instructions were brief and staccato as if part of the unfolding suite. When he did pick up the microphone to speak to the audience he exuded an eccentric charm, bandstand asides peppered with self-effacing humour, garnished with sudden smiles.

To the best of my knowledge, Jonathan Besser has not played at the CJC (Creative Jazz Club) before. While he is best known as an important composer for The New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, The New Zealand String Quartet and The Royal New Zealand Ballet, he is also a significant leader of small ensembles. Ensembles which venture far into the territory of experimental, electronic and improvised music. It is impossible to separate the man from his music. It is eclectic, original and often plaintive but generally with a sly twist of humour thrown in. In spite of his standing in the music world, Besser is modest. At the CJC he was happy to lead from the piano, which was in partial darkness and at the rear of the ensemble. His instructions were brief and staccato as if part of the unfolding suite. When he did pick up the microphone to speak to the audience he exuded an eccentric charm, bandstand asides peppered with self-effacing humour, garnished with sudden smiles.

I met Besser briefly during Natalia Mann’s ‘Pacif.ist’ tour and later at the Auckland Art Gallery during the opening of Billy Apples ‘Sound Works’ exhibition. On that occasion, the Nathan Haines Quartet played Besser’s innovative compositions. I really hope that someone recorded that. It was extraordinary music, based upon prescribed letters of the alphabet. These were then allocated using the 12 tone scale as a formula to locate equivalent notes. The order of Billy Apple’s words dictating the order of notes.

I met Besser briefly during Natalia Mann’s ‘Pacif.ist’ tour and later at the Auckland Art Gallery during the opening of Billy Apples ‘Sound Works’ exhibition. On that occasion, the Nathan Haines Quartet played Besser’s innovative compositions. I really hope that someone recorded that. It was extraordinary music, based upon prescribed letters of the alphabet. These were then allocated using the 12 tone scale as a formula to locate equivalent notes. The order of Billy Apple’s words dictating the order of notes. The music was not Klezmer and later I asked Besser about his influences – were there strong Jewish influences? “I am a Jewish man and I used Jewish scales, but apart from that no. I draw upon many, sources”. It interested him that I heard Argentinian references. “I have done Tango projects in the past and that is possible”. It was partly the combination of instruments, the delicious overlay of melancholia and the accents – not so far from the music of master musician Dino Saluzzi.

The music was not Klezmer and later I asked Besser about his influences – were there strong Jewish influences? “I am a Jewish man and I used Jewish scales, but apart from that no. I draw upon many, sources”. It interested him that I heard Argentinian references. “I have done Tango projects in the past and that is possible”. It was partly the combination of instruments, the delicious overlay of melancholia and the accents – not so far from the music of master musician Dino Saluzzi. The segments of music making up the suite seldom lasted longer than 4 minutes. The spaces between them brief. The mood seldom deviated from the wistful, evoking a sense of intangible longing – for something remembered – but just out of reach, a nostalgia as ancient as time itself. There were a few cheerful pieces as well, but I preferred the former. The Zestniks update themselves regularly, this time adding Caro Manins vocal lines, her wordless vocals followed the viola or clarinet in gentle unison. No one is better suited to this than Manins – she has worked with the likes of Norma Winstone after all.

The segments of music making up the suite seldom lasted longer than 4 minutes. The spaces between them brief. The mood seldom deviated from the wistful, evoking a sense of intangible longing – for something remembered – but just out of reach, a nostalgia as ancient as time itself. There were a few cheerful pieces as well, but I preferred the former. The Zestniks update themselves regularly, this time adding Caro Manins vocal lines, her wordless vocals followed the viola or clarinet in gentle unison. No one is better suited to this than Manins – she has worked with the likes of Norma Winstone after all.

Thanks to Rodger Fox and the CJC management we were lucky enough to see five times Grammy nominee, Jazz vocalist Karrin Allyson in our Auckland Jazz Club last Wednesday night. Seeing an artist like this in a concert hall is one thing; seeing her in the warm intimate surroundings of a small Jazz club and just a metre away is quite another. Always a sucker for quality Jazz vocalists I first heard her in 1992 (the album ‘I Thought About You’ was the first of hers I purchased). On the basis of her recorded output, I booked for both the CJC gig in Auckland and the Wellington Jazz Festival concert. The flights between these cities are surprisingly affordable when you book in advance, and these opportunities don’t come around often when you live in the South Pacific.

Thanks to Rodger Fox and the CJC management we were lucky enough to see five times Grammy nominee, Jazz vocalist Karrin Allyson in our Auckland Jazz Club last Wednesday night. Seeing an artist like this in a concert hall is one thing; seeing her in the warm intimate surroundings of a small Jazz club and just a metre away is quite another. Always a sucker for quality Jazz vocalists I first heard her in 1992 (the album ‘I Thought About You’ was the first of hers I purchased). On the basis of her recorded output, I booked for both the CJC gig in Auckland and the Wellington Jazz Festival concert. The flights between these cities are surprisingly affordable when you book in advance, and these opportunities don’t come around often when you live in the South Pacific. Following her 1992 release further albums came out and by the time ‘Ballads: for Coltrane’ and ‘In Blue’ were released there was no mistaking it. This was an important vocal interpreter. Her voice has particular qualities, an attractive smoky veneer, but then there’s that extra something. A sense of shared intimacy, a way of interpreting lyrics in an original way while still paying tribute to earlier interpreters. Her version of ‘O Barquino’ or ‘Double Rainbow’ (both by Jobim) immediately brings to mind the fabulous Elis Regina. Her ‘West Coast Blues’ conjures up Wes Montgomery just as much as the instrumentalists. She scats in ways that adds value to the narrative content of the song, never overdone and always wonderfully inventive. It came as no surprise, therefore, that she could conquer an audience in a heart beat.

Following her 1992 release further albums came out and by the time ‘Ballads: for Coltrane’ and ‘In Blue’ were released there was no mistaking it. This was an important vocal interpreter. Her voice has particular qualities, an attractive smoky veneer, but then there’s that extra something. A sense of shared intimacy, a way of interpreting lyrics in an original way while still paying tribute to earlier interpreters. Her version of ‘O Barquino’ or ‘Double Rainbow’ (both by Jobim) immediately brings to mind the fabulous Elis Regina. Her ‘West Coast Blues’ conjures up Wes Montgomery just as much as the instrumentalists. She scats in ways that adds value to the narrative content of the song, never overdone and always wonderfully inventive. It came as no surprise, therefore, that she could conquer an audience in a heart beat. From the first vocal number, Allyson teased the audience, turning the lyrics into a conversation. Her set list spanned her Concord recordings including her recent release ‘Many a New Day: Karrin Allyson Sings Rogers & Hammerstein’ (When I think of Tom/Hello Young Lovers). Everything she performed was extraordinary but when she moved to the piano and accompanied herself on ‘Bye Bye Country Boy’ I was especially delighted. For some unaccountable reason, few vocalists interpret Blossom Dearie and more’s the pity. Dearie was a true original and a fiendishly clever Jazz vocalist. Her voice had a deceptive depth if you listened properly and like Allyson her ability to communicate was perfectly honed. It is fitting that Allyson should tackle Blossom Dearie as she is able to convey the same wry humour and wrap it up in a very attractive vocal package. She was simply killing in her interpretation.

From the first vocal number, Allyson teased the audience, turning the lyrics into a conversation. Her set list spanned her Concord recordings including her recent release ‘Many a New Day: Karrin Allyson Sings Rogers & Hammerstein’ (When I think of Tom/Hello Young Lovers). Everything she performed was extraordinary but when she moved to the piano and accompanied herself on ‘Bye Bye Country Boy’ I was especially delighted. For some unaccountable reason, few vocalists interpret Blossom Dearie and more’s the pity. Dearie was a true original and a fiendishly clever Jazz vocalist. Her voice had a deceptive depth if you listened properly and like Allyson her ability to communicate was perfectly honed. It is fitting that Allyson should tackle Blossom Dearie as she is able to convey the same wry humour and wrap it up in a very attractive vocal package. She was simply killing in her interpretation. Accompanying Allyson was the Tom Warrington trio. Although it is five years since we saw them last, they have been regular visitors to New Zealand thanks to Fox. Tom Warrington is a superb bassist, having worked with everyone from Peggy Lee to Stan Getz. His list of credits is staggering. Formerly based in LA, where he was constantly in demand and no wonder. The choices underpinning each note he plays are beyond caveat. His musicality, teaching and compositional skills of the highest order. Today he lives a quieter life in rural New Zealand. When you hear his bass lines, and especially during a ballad, you recall the classic piano-trio bass players. Loading each note with meaning and carrying as much weight as any chordal instrument. Warrington has released four superb albums with this trio and all are highly recommended.

Accompanying Allyson was the Tom Warrington trio. Although it is five years since we saw them last, they have been regular visitors to New Zealand thanks to Fox. Tom Warrington is a superb bassist, having worked with everyone from Peggy Lee to Stan Getz. His list of credits is staggering. Formerly based in LA, where he was constantly in demand and no wonder. The choices underpinning each note he plays are beyond caveat. His musicality, teaching and compositional skills of the highest order. Today he lives a quieter life in rural New Zealand. When you hear his bass lines, and especially during a ballad, you recall the classic piano-trio bass players. Loading each note with meaning and carrying as much weight as any chordal instrument. Warrington has released four superb albums with this trio and all are highly recommended. On chordal duties was Larry Koonse, playing a lovely hollow body Borys guitar. An impressive guitarist and a stalwart of the LA Jazz scene. Again, he is widely recorded, also releasing a number of albums under his own name. In many ways, Koonse encapsulates the best of the pre-millennial guitar tradition. That said, his fresh approach to tunes is also very much evident. His voice leading is a masterclass; dissonant/consonant inversions that have more bottom than most guitarists can muster in a lifetime and a gorgeous warm tone which lingers in the memory long after the gig. This, together with his other skills, makes him the perfect accompanist for a vocalist. When he played ‘Bolivia’ (Cedar Walton) with the trio, it took on the urgency and excitement that the tune demands. On ‘Whisper Not’ (Benny Golson) he extracted unalloyed beauty. I have known Larry for a decade and speaking to him after the gig, I complimented him on those tunes. At that point, my mouth raced way ahead of my brain and I said, “that was ‘Speak Low’ wasn’t it”? That fact that my slip of the tongue had accidentally come up with an exact antonym of ‘Whisper not’ made his day.

On chordal duties was Larry Koonse, playing a lovely hollow body Borys guitar. An impressive guitarist and a stalwart of the LA Jazz scene. Again, he is widely recorded, also releasing a number of albums under his own name. In many ways, Koonse encapsulates the best of the pre-millennial guitar tradition. That said, his fresh approach to tunes is also very much evident. His voice leading is a masterclass; dissonant/consonant inversions that have more bottom than most guitarists can muster in a lifetime and a gorgeous warm tone which lingers in the memory long after the gig. This, together with his other skills, makes him the perfect accompanist for a vocalist. When he played ‘Bolivia’ (Cedar Walton) with the trio, it took on the urgency and excitement that the tune demands. On ‘Whisper Not’ (Benny Golson) he extracted unalloyed beauty. I have known Larry for a decade and speaking to him after the gig, I complimented him on those tunes. At that point, my mouth raced way ahead of my brain and I said, “that was ‘Speak Low’ wasn’t it”? That fact that my slip of the tongue had accidentally come up with an exact antonym of ‘Whisper not’ made his day. Last but not least is the Warrington Trio drummer Joe La Barbera. No one needs reminding of his long list of credits and impeccable credentials. As Warrington said during the introductions. “As everyone knows, Joe La Barbera was in the last Bill Evans trio. This puts us in some rarefied air”. Along with Marc Johnson, he breathed new life into that trio. While rightly famous for his superb drum work with Evans, he is a multi-faceted drummer; having also worked in avant-garde settings and with medium to larger sized ensembles such as ‘The West Coast All Stars’, ‘The Woody Herman Band’ and with ‘Kenny Wheeler’. He has often worked with famous vocalists such as Tony Bennett and Karrin Allyson. La Barbera has an inclusive quality that enhances bass and guitar but never overshadows them. When he solos, it is to the point. His stick and brush work add subtlety and texture – the effect always jaw-dropping. It is easy to see why he is so much in demand. A musical drummer who gives so much while working so hard to support the others.

Last but not least is the Warrington Trio drummer Joe La Barbera. No one needs reminding of his long list of credits and impeccable credentials. As Warrington said during the introductions. “As everyone knows, Joe La Barbera was in the last Bill Evans trio. This puts us in some rarefied air”. Along with Marc Johnson, he breathed new life into that trio. While rightly famous for his superb drum work with Evans, he is a multi-faceted drummer; having also worked in avant-garde settings and with medium to larger sized ensembles such as ‘The West Coast All Stars’, ‘The Woody Herman Band’ and with ‘Kenny Wheeler’. He has often worked with famous vocalists such as Tony Bennett and Karrin Allyson. La Barbera has an inclusive quality that enhances bass and guitar but never overshadows them. When he solos, it is to the point. His stick and brush work add subtlety and texture – the effect always jaw-dropping. It is easy to see why he is so much in demand. A musical drummer who gives so much while working so hard to support the others.

Auckland spoils us with long runs of clement weather, but when winter hits we suffer. Having effectively avoided any meaningful autumn we suddenly plunged into a week of cold wet days. There was no better time for the Michel Benebig/Carl Lockett band to arrive. As we grooved to the music, a warmth flooded our bodies within minutes. Nothing invokes warmth like a well oiled B3 groove unit and the Benebig/Locket band is as good as it gets. The icing on the cake was seeing Shem with them. A singer with incredible modulation skills and perfect pitch, able to convey the nuances of emotion with a casual glance or a single note. The way she moves from the upper register to the midrange, silken.

Auckland spoils us with long runs of clement weather, but when winter hits we suffer. Having effectively avoided any meaningful autumn we suddenly plunged into a week of cold wet days. There was no better time for the Michel Benebig/Carl Lockett band to arrive. As we grooved to the music, a warmth flooded our bodies within minutes. Nothing invokes warmth like a well oiled B3 groove unit and the Benebig/Locket band is as good as it gets. The icing on the cake was seeing Shem with them. A singer with incredible modulation skills and perfect pitch, able to convey the nuances of emotion with a casual glance or a single note. The way she moves from the upper register to the midrange, silken. Michel Benebig has been travelling to New Zealand for years, and his connection with the principals of the UoA Jazz school has been a boon for us. He generally brings his partner Shem with him, but last time work commitments in her native New Caledonia kept her at home. Michel just gets better and better and the way his pedal work and hands create contrasts and tension defies belief. It is therefore not surprising that Michel attracts top rated guitarists or saxophonists to his bands. The best of our local groove guitarists have often featured and a growing number of stand-out American artists (see earlier posts on this band). Of these, the New York guitarist Carl Locket is of particular note. I first heard Lockett in San Francisco four years ago and he mesmerised me with his deep bluesy lines and time feel. Although comfortable in a number of genres, he is the ideal choice for an organ/guitar groove unit.