Jim left us in January, and the shock of his unexpected passing robbed me of the right words. In the following weeks, I mulled over my inaction, wanting to do justice to his story? Then I caught covid and more time passed. While it is usual to post an obituary within days of someone passing, I paused and reflected. And as I deliberated, I could sense his presence, knowing that he would approve of my waiting until the right words appeared. Jim’s life was a Zen koan, and you can’t rush a koan.

We had spoken on the phone a week before he died and arranged a ‘hang’ in a nearby coffee bar. It was sometimes hard to catch him on the phone, but when he picked up you could feel the warmth radiating from the handset. The conversations were slow grooves. He would speak softly, radiate peace and intersperse his comments with periods of reflective silence. Jim seldom rushed his words, and the silences felt all the more weighty for it. He spoke as he played because he understood the power of space between sounds.

I had known him for over a decade, but I wished I had known him for longer. He was a musician’s musician; the term used to describe a player of significance but one who is scandalously under-acknowledged. He had been on the Jazz scene his entire adult life and had played alongside some of the greats, but his natural habitats were in the Spiritual Jazz and avant-garde scenes. Many assume that the music of the avant-garde is strident. In Jim’s hands, the music was reflective, spiritual and embedded in indigenous culture.

He could crack open a note and let it breathe in multi-phonic splendour. He could whisper into a flute and then unexpectedly send forth a flurry of breathy overtones. He had great chops and visionary ideas, but he was not egotistical. Jim was about the music and not about himself. He was an educator and an empowerer. It was about transmission – telling the story, enjoying the moment and passing on the flame.

He had written the liner notes for one of the first American Spiritual Jazz albums incorporating his Buddhist name (Tony Scott’s ‘Music for Zen Meditation). He’d recorded with poets and acolytes and played alongside Dave Liebman and Gary Peacock. He also had a presence on many New Zealand albums but seldom as a leader. At first, I put this down to modesty, but now I think otherwise. His musical journey inclined him towards humility; he possessed that in the best sense. Gentle souls leave softer footprints.

He gave more to music than he received; to understand why you should know something else about Jim, his long involvement with Zen Buddhism. It was a particular connection that we had. Each of us had connected with Buddhism in our youth which informed our attitude towards in-the-moment music. Although I meditated then, mine was of the Beat variety of Zen, remaining a lazy ‘psychedelic’ Buddhist. Jim took his practice seriously, spending time in Zen Mountain Monastery, Mt Tremper, upper New York State.

While on that scene he performed with other spiritually engaged Jazz musicians like Gary Peacock, Chris Dahlgren and Jay Weik. And amazingly, performed with famous Beat poets like Alan Ginsberg and Anne Waldman who had an association with the centre, and together, had set up the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute. In New York, he connected with Tony Scott and Dave Liebman. Later, Jim established a New Zealand Sangha in the ZMM lineage and brought out their first teacher.

I recall messaging him when I was last in San Francisco to tell him I was seeking the forgotten Jazz Clubs, the homes of lost poets and the San Francisco Zen Centre. Names leapt across the cyber-void, Black Hawk, Kerouac, Kaufman and DiPrima. Back and forth we messaged during that week. He, tapping out fragmentary reminisces of his Dharma experiences in America and recalling some of the Jazz musicians he’d encountered (eg. Jaco Pastorius, Rashid Ali, Arthur Rhames, Gary Peacock, Dave Leibman).

I, responded with pictures of a priceless Rupa as I stood in the Zen Centre Meditation room; buying a new translation of Han Shan’s Cold Mountain poems and sending him a picture of the cover. And me, reliving Ginsberg’s visions of Moloch as I wandered the corridors of his trippy nemesis, the Sir Francis Drake hotel. Buddhist practice, poetry and improvised music are old acquaintances. It was our instinctive connection.

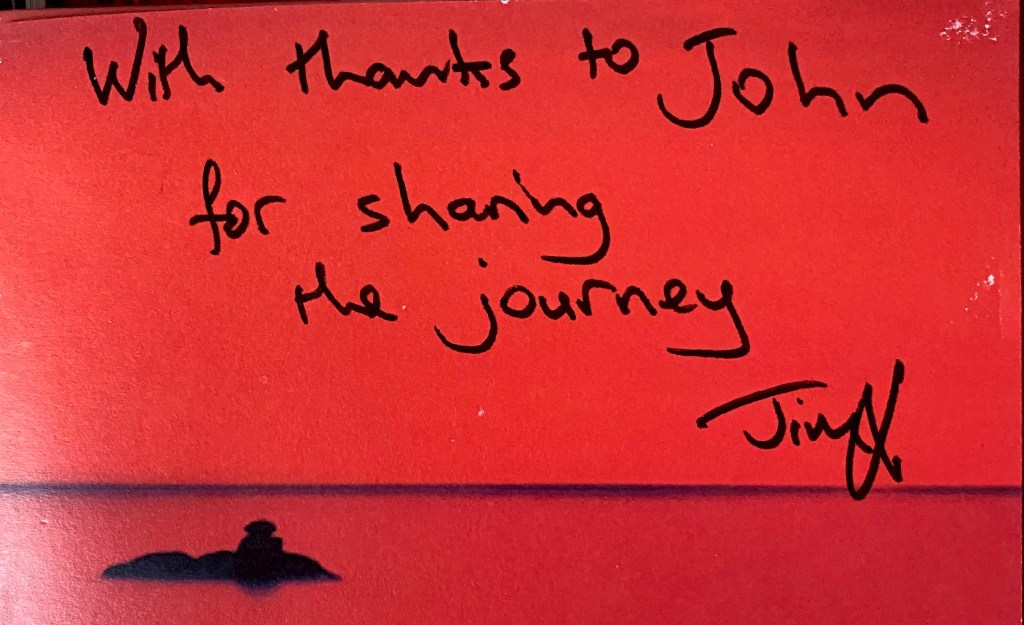

I would bump into Jim at gigs. And he would say, “I hoped you’d be here, I have this for you” passing over a booklet on Finnish Jazz or a CD. He would press them into my hand without explanation and carry on talking about other things. These were Zen puzzles for me to unravel. I realised what treasures they were only later.

He came to my seventieth birthday, a house party where he enjoyed the young musicians playing. He was photographed, deploying his best smile as he posed among us. On that occasion, he handed me a bag of goodies, a limited edition double album – a live concert featuring Arthur Rhames, Jaco Pastorius and Rashid Ali. Handwritten by sharpie was the cryptic inscription ‘jimjazz ⅕’ – another koan to solve. Did he record this?

Important chroniclers like Norman Meehan have written about him, but I’m sure there is more to say. His family and musician friends will create a fuller discography, preserve his charts and update his filmography. It is important. Because he was not a self-promoter, he could surprise you when he appeared in line-ups. With Indian vocalists like Sandhya Sanjana, Tom Ludvigson & Trever Reekie’s Trip to the Moon band, at the NZ Music Awards, at numerous Jazz Festivals and on movie soundtracks. And he played and contributed to daughter Rosie Langabeer’s various out-ensembles. He played the flute on the ‘Mr Pip’ soundtrack and saxophone on daughter Rosie Langabeer’s soundtrack for the indie film GODPLEX

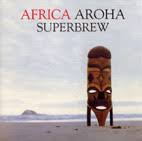

He released at least two notable local albums as a leader, but perhaps there are more? Jim’s Africa/Aroha album with Barry Young (SUPERBREW) was released as an LP by Ode in 1984 and re-released in 2007. It has remained popular with jazz lovers. Prophetically, his composition Aroha cropped up on the hospital Spotify playlist during his last hours. The album broke fresh ground in New Zealand with its freedom-tinged Afrobeat and World Jazz influences. It is gorgeous.

Around 2016 Jim undertook a research and performance project at the Auckland University Jazz School, where he was awarded a Masters’s Degree with first-class Honours. Out of that came his finest recording Secret Islands (Rattle). After recording, Jim phoned me and asked if I would write the liner notes and I was pleased to be on board. He also used my photographs.

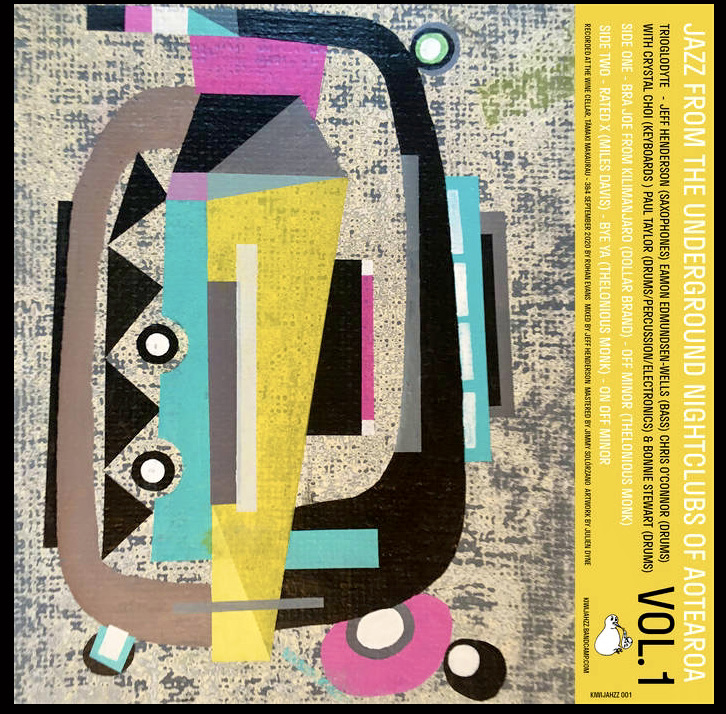

I am an enthusiast of avant-garde music and a fan of Jim’s approach, so it was a labour of love. Secret Islands is one of a select group of albums that tells a New Zealand Jazz story. It could not have come from anywhere else. I had heard the band play a preview of the album and loved what I heard. The recording took things to another level. It featured an all-star lineup. With Jim’s vision and Rosie and the other player’s contributions, it was sure to hit a sweet spot. Later a live performance was reprised at the Audio Foundation with Jim on flute and tenor, Jeff Henderson on drums, Rosie Langabeer on Piano, Neil Feather on an experimental instrument and Eamon Edmundson-Wells on bass, with Roger Manins on Alto. It was a superb performance. I will never forget it. The Secret Islands album (clip above) featured Jim Langabeer on winds and reeds, Rosie Langabeer, piano and Fender Rhodes, Neil Watson, guitars, Eamon Edmundson-Welles, bass, Roger Manins, alto saxophone and Chris O’Connor, drums.

One last album that deserves mention is One Way Ticket – Daikajo. Released in 1995 by ‘Dharma Communications’ Zen Mountain Zen Monestry NY and produced by Jim. On it, he leads the ensemble on alto saxophone, silver flute and shakuhachi. Like most of Jim’s albums, it is Spiritual Jazz. A subgenre of improvised music that is experiencing revival worldwide.

Just before the first lockdown, I visited him at his Farm Cove home as I wanted to record an oral history. I switched on my recorder while the conversation ran for two or three hours. It often veered into the esoteric. When Ī played it back, I realised that I needed another session with a greater focus on Jim’s achievements. I can usually keep an interview on track, but in Jim’s case, words were like pebbles in a pond. A series of moments setting off ripples haiku-like.

Before I knew it the pandemic had arrived. I had lost my window of opportunity. Jim passed at the height of the second lockdown, and much as I wanted to attend his funeral, I couldn’t. I participated online and remembered him in silence, a copy of Secret Islands beside me and his tune Tangi playing softly in the other room. We loved Jim and mourn his untimely passing.

Footnote: The Rupa (Buddhist image) is an antique statue located in the San Francisco Zen Centre. It is likely the Bodhisattva Kuan Yin or Maitreya in Bodhisattva form. The video is Jim’s tune Ananda’s Midnight Blues which I filmed at CJC Jazz Club, Auckland. I have also included the clip ‘Tangi’ from Secret Islands. Lastly, I would like to fondly acknowledge Jim’s daughters, Rosie, Catherine and Celia Langabeer, and Jim’s partner Lyndsey Knight, who together, acted as fact-checkers.

JazzLocal32.com is rated one of the 50 best Jazz Blogs in the world by Feedspot. The author is a professional member of the Jazz Journalists Association, poet & writer. Some of these posts appear on other sites with the author’s permission.

There is a world of interesting music happening at the Audio Foundation and this three-set gig exemplified the foundations imaginative ahead of the game programming. The evening featured a cross-section of music from the fully arranged to the unconstrained and free. From the open dialogue of the Knotted Throats to the carefully crafted texturally rich four-piece voicings of a jazz ensemble. Then, and perhaps this is the essence of the programming, the two groups merged and out of that came a declaration. Sound exists without boundaries. The borders and demarcation lines as we organise or sculpt sound are only human constructs and beyond these artificial barriers, the various languages merge. When that occurs music is the richer for it. Improvised music is always on the move and just as post-bop moved seamlessly between free, fusion, hard bop, bop and groove, so the journey continues.

There is a world of interesting music happening at the Audio Foundation and this three-set gig exemplified the foundations imaginative ahead of the game programming. The evening featured a cross-section of music from the fully arranged to the unconstrained and free. From the open dialogue of the Knotted Throats to the carefully crafted texturally rich four-piece voicings of a jazz ensemble. Then, and perhaps this is the essence of the programming, the two groups merged and out of that came a declaration. Sound exists without boundaries. The borders and demarcation lines as we organise or sculpt sound are only human constructs and beyond these artificial barriers, the various languages merge. When that occurs music is the richer for it. Improvised music is always on the move and just as post-bop moved seamlessly between free, fusion, hard bop, bop and groove, so the journey continues.

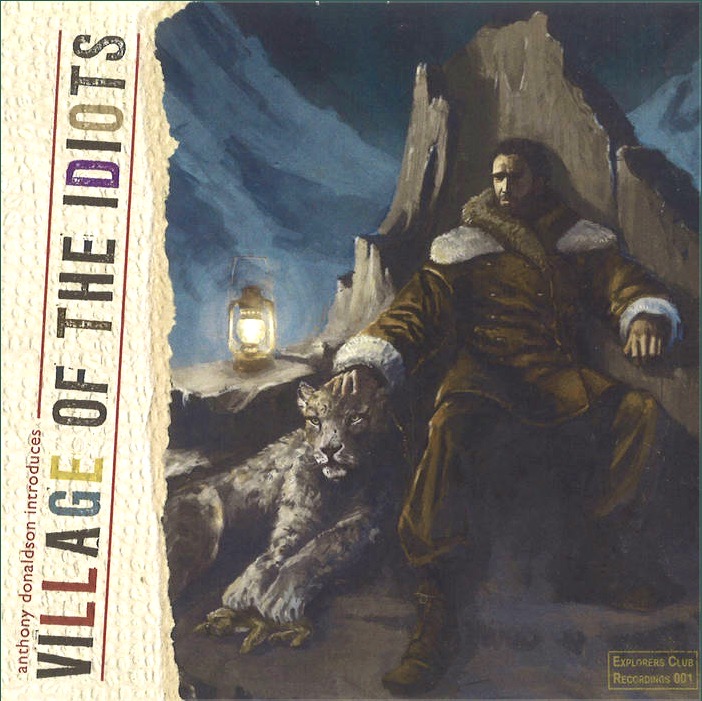

Anything that Jeff Henderson is associated with is likely to be intense, mind-altering and extraordinary. No matter how prepared you think that you are, you should understand that your head will be fucked with. When you factor in Tom Callwood, Anthony Donaldson and Daniel Beban the Henderson effect is magnified exponentially. This music is powerful stuff as it sweeps aside genres as irrelevant distractions. When confronted with a gig like this you abandon preconceptions, as the sonic smorgasbord jolts you out of complacency. It is also a visual experience and Fellini would have signed these guys up in a heart-beat.

Anything that Jeff Henderson is associated with is likely to be intense, mind-altering and extraordinary. No matter how prepared you think that you are, you should understand that your head will be fucked with. When you factor in Tom Callwood, Anthony Donaldson and Daniel Beban the Henderson effect is magnified exponentially. This music is powerful stuff as it sweeps aside genres as irrelevant distractions. When confronted with a gig like this you abandon preconceptions, as the sonic smorgasbord jolts you out of complacency. It is also a visual experience and Fellini would have signed these guys up in a heart-beat.

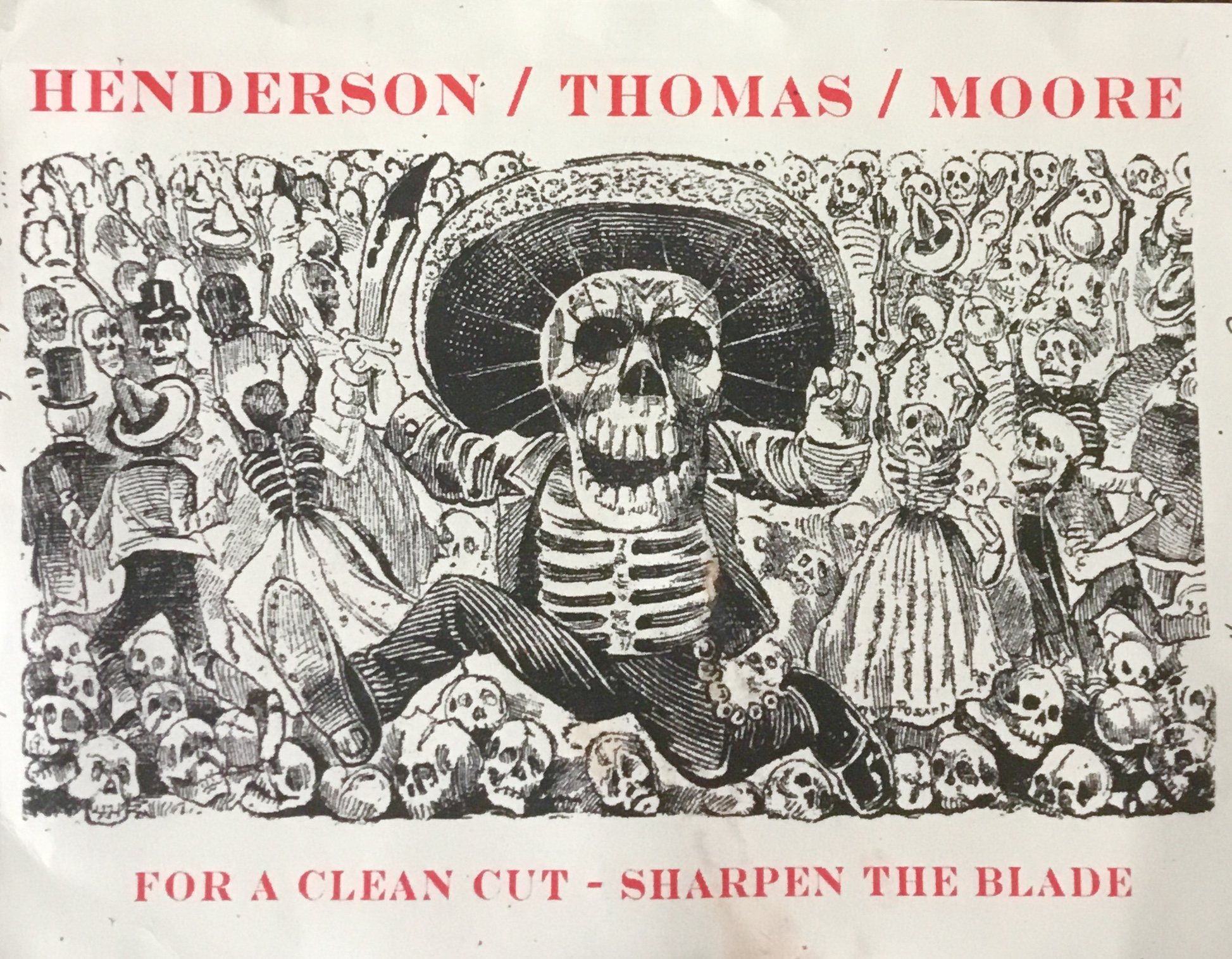

Jeff Henderson is a freedom warrior from outside of the perimeter fence. On the 9th of May, 2018, he marched barefooted into the Backbeat Bar with a ragtag army of irregulars. The audience had come well prepared and a pregnant air of anticipation hung over the bandstand during setup. Unusually, there were no lower ranks in this army, all were battle-hardened veterans (or anti-heroes depending on your viewpoint). All had impressive service records, an advance guard who took no prisoners. Jonathan Crayford is arguably the most famous of the troop, a decorated hero who swiftly commandeered a C3 organ (an ancient analogue machine decorated by psychedelic art and reminiscent of a Haight Asbury weed shop). Beside him sat machine gunner Steve Cournane, a rat-tat-tat freedom fighter recently returned from Peru. The remaining soldier, battle scared and bleeding, was Eamon Edmundson-Wells (his Viking surname tells it’s own story).

Jeff Henderson is a freedom warrior from outside of the perimeter fence. On the 9th of May, 2018, he marched barefooted into the Backbeat Bar with a ragtag army of irregulars. The audience had come well prepared and a pregnant air of anticipation hung over the bandstand during setup. Unusually, there were no lower ranks in this army, all were battle-hardened veterans (or anti-heroes depending on your viewpoint). All had impressive service records, an advance guard who took no prisoners. Jonathan Crayford is arguably the most famous of the troop, a decorated hero who swiftly commandeered a C3 organ (an ancient analogue machine decorated by psychedelic art and reminiscent of a Haight Asbury weed shop). Beside him sat machine gunner Steve Cournane, a rat-tat-tat freedom fighter recently returned from Peru. The remaining soldier, battle scared and bleeding, was Eamon Edmundson-Wells (his Viking surname tells it’s own story).

Lately I have attended a number of music workshops. Although not a musician I gain a lot. They offer fascinating insights into the artists creative process and if your lucky, insights into a particular instrument. With music, the more you listen, learn, observe and delve, the more you gain. My reason for attending Susan Alcorn’s workshop was probably different from most attendees. The majority were guitarists anxious to glean practical information or wanting to be convinced that this complex instrument was for them. A handful of others sought knowledge for knowledges sake – dipping another toe in the water of sonic learning.

Lately I have attended a number of music workshops. Although not a musician I gain a lot. They offer fascinating insights into the artists creative process and if your lucky, insights into a particular instrument. With music, the more you listen, learn, observe and delve, the more you gain. My reason for attending Susan Alcorn’s workshop was probably different from most attendees. The majority were guitarists anxious to glean practical information or wanting to be convinced that this complex instrument was for them. A handful of others sought knowledge for knowledges sake – dipping another toe in the water of sonic learning.

cleverness your ideas. It is about integrity. Musical integrity is rare but universally available.

cleverness your ideas. It is about integrity. Musical integrity is rare but universally available. makes you glad that you’re alive. Touring New Zealand with Nock were James ‘Pug’ Waples (drums) and Brett Hirst (bass)’. These musicians while deeply attuned to each other were always full of surprises. 5 stars. *****

makes you glad that you’re alive. Touring New Zealand with Nock were James ‘Pug’ Waples (drums) and Brett Hirst (bass)’. These musicians while deeply attuned to each other were always full of surprises. 5 stars. ***** Whether as accompanist or soloist, Field shines. His work in 2014 on ‘Dog’, with Caitlin Smith and with the Australian saxophonist Jamie Oehlers stand out as high points. Adam Ponting (Aust) (Hip Flask ‘1’ & ’11’). Ponting is an unusual but compelling pianist. An original stylist who appears to approach tunes from an oblique angle, at first impressionistic, but leading you into a world of funky satisfying grooves. This guy is definitely someone I would like to hear again. It was also great to hear more of Alan Brown (NZ) on piano during 2014. He has some interesting piano and keys projects underway and we will hear more of those soon. Steve Barry (Aust). Barry is an ex pat Auckland pianist now based in Australia. He visited New Zealand twice during 2014. His visits and albums are always received enthusiastically. Barry is a musician who works hard and produces the goods. His new album ‘Puzzles’ with Dave Jackson (alto), Alex Boneham (bass) and Tim Firth, lifts the bar for up and coming local musicians. We had a number of visitors in 2014 and to bring us a European perspective was the Benny Lackner Trio (Germany/USA). The pianist Benny Lackner has visited New Zealand on several previous occasions and the aesthetic he brings is finely honed. The band has a similar feel to EST. There is the occasional use of electronics and they quickly find tasty grooves that could only emanate from a European Band.

Whether as accompanist or soloist, Field shines. His work in 2014 on ‘Dog’, with Caitlin Smith and with the Australian saxophonist Jamie Oehlers stand out as high points. Adam Ponting (Aust) (Hip Flask ‘1’ & ’11’). Ponting is an unusual but compelling pianist. An original stylist who appears to approach tunes from an oblique angle, at first impressionistic, but leading you into a world of funky satisfying grooves. This guy is definitely someone I would like to hear again. It was also great to hear more of Alan Brown (NZ) on piano during 2014. He has some interesting piano and keys projects underway and we will hear more of those soon. Steve Barry (Aust). Barry is an ex pat Auckland pianist now based in Australia. He visited New Zealand twice during 2014. His visits and albums are always received enthusiastically. Barry is a musician who works hard and produces the goods. His new album ‘Puzzles’ with Dave Jackson (alto), Alex Boneham (bass) and Tim Firth, lifts the bar for up and coming local musicians. We had a number of visitors in 2014 and to bring us a European perspective was the Benny Lackner Trio (Germany/USA). The pianist Benny Lackner has visited New Zealand on several previous occasions and the aesthetic he brings is finely honed. The band has a similar feel to EST. There is the occasional use of electronics and they quickly find tasty grooves that could only emanate from a European Band. winner Broadbent is our best known improvising export and he has spent the last year touring Europe and America to great acclaim. The solo album was given a rare 5 star rating by downbeat and ‘America The Beautiful’ was recently voted one of the 10th best albums of 2014.

winner Broadbent is our best known improvising export and he has spent the last year touring Europe and America to great acclaim. The solo album was given a rare 5 star rating by downbeat and ‘America The Beautiful’ was recently voted one of the 10th best albums of 2014. Samsom. It sizzles, swings and while hinting at the vibe of a bygone era, it still sounds fresh & modern (and very Kiwi). ‘Dark Light’ (Rattle Jazz) This excellent album is one of two that Jonathan Crayford released in 2014 – Recorded at ‘Systems Two Studio’ NY with Crayford (piano), Ben Street (bass), Dan Weiss (drums). Don’t expect repetition from Crayford. This master musician takes us on many journey’s, each unlike the last and all brilliant. Hip Flask 2 (Rattle Jazz) A funk unit led by Australasian saxophone giant Roger Manins. Accompanied by Adam Ponting (piano), Stu Hunter (organ), Brendan Clarke (bass) and Toby Hall (drums). A thoroughly appealing album and a welcome follow-up to Hip Flask 1 (Hip Flask 1 included with the album).

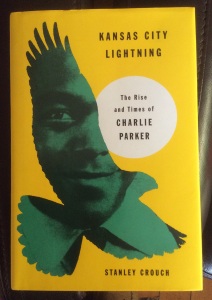

Samsom. It sizzles, swings and while hinting at the vibe of a bygone era, it still sounds fresh & modern (and very Kiwi). ‘Dark Light’ (Rattle Jazz) This excellent album is one of two that Jonathan Crayford released in 2014 – Recorded at ‘Systems Two Studio’ NY with Crayford (piano), Ben Street (bass), Dan Weiss (drums). Don’t expect repetition from Crayford. This master musician takes us on many journey’s, each unlike the last and all brilliant. Hip Flask 2 (Rattle Jazz) A funk unit led by Australasian saxophone giant Roger Manins. Accompanied by Adam Ponting (piano), Stu Hunter (organ), Brendan Clarke (bass) and Toby Hall (drums). A thoroughly appealing album and a welcome follow-up to Hip Flask 1 (Hip Flask 1 included with the album). biography is the weakest link in Jazz Writing. If that is true then the mould has truly been broken with this work. Crouch has placed the story of Parker’s early life into a fuller historical context. In learning things about the times, we learn a lot about the man. This is a book that could be appreciated by anyone interested in the history of African-American life in the Mid-West. I suspect that its significance will grow as time passes. Above all the book is beautifully written and for me that counts.

biography is the weakest link in Jazz Writing. If that is true then the mould has truly been broken with this work. Crouch has placed the story of Parker’s early life into a fuller historical context. In learning things about the times, we learn a lot about the man. This is a book that could be appreciated by anyone interested in the history of African-American life in the Mid-West. I suspect that its significance will grow as time passes. Above all the book is beautifully written and for me that counts.

This was too good an opportunity not to record and Rattle did just that. Capturing chordal instruments in a space like the CJC is challenging as the sound has a number of hard edges to bounce off. Recording a live performance of this particular brand of ‘Troubles’ might work well.

This was too good an opportunity not to record and Rattle did just that. Capturing chordal instruments in a space like the CJC is challenging as the sound has a number of hard edges to bounce off. Recording a live performance of this particular brand of ‘Troubles’ might work well.  Guiding the proceedings with his well-known brand of anti-establishment megaphone diplomacy was ring master John Rae, ‘Troubles’ co-founder. He shepherded the ensemble through a constantly shifting landscape. His effervescent flow of joyous and often irreverent cries only stemmed by Patrick Bleakley’s timely interjections. Rae is the supercharged engine room, but Bleakley is clearly the anchor. Like Rae he’s an original member.

Guiding the proceedings with his well-known brand of anti-establishment megaphone diplomacy was ring master John Rae, ‘Troubles’ co-founder. He shepherded the ensemble through a constantly shifting landscape. His effervescent flow of joyous and often irreverent cries only stemmed by Patrick Bleakley’s timely interjections. Rae is the supercharged engine room, but Bleakley is clearly the anchor. Like Rae he’s an original member.  With this Auckland horn section in place, a new front had opened and the tweaked charts took maximum advantage of that. On baritone was Ben McNicoll and his presence gave the sound added bottom. Roger Manins, who had stunned us with his wild death-defying solo’s at the Troubles Portland Public House gig was on tenor again. Jeff Henderson took the alto spot and that was a significant addition. His ultra powerful unblinking delivery was the x-factor. Unafraid of repeated motifs but able to negotiate the music without ever resorting to the familiar. That is the Henderson brand, original clear-cut and uncompromising. In no way diminished by the powerful reed instruments surrounding him was Kingsley Melhuish on trumpet. Melhuish has a rich burnished sound and like the others, he is no stranger to musical risk taking.

With this Auckland horn section in place, a new front had opened and the tweaked charts took maximum advantage of that. On baritone was Ben McNicoll and his presence gave the sound added bottom. Roger Manins, who had stunned us with his wild death-defying solo’s at the Troubles Portland Public House gig was on tenor again. Jeff Henderson took the alto spot and that was a significant addition. His ultra powerful unblinking delivery was the x-factor. Unafraid of repeated motifs but able to negotiate the music without ever resorting to the familiar. That is the Henderson brand, original clear-cut and uncompromising. In no way diminished by the powerful reed instruments surrounding him was Kingsley Melhuish on trumpet. Melhuish has a rich burnished sound and like the others, he is no stranger to musical risk taking.  Together they evoked a spirit close to the earlier manifestations of the Liberation Jazz Orchestra. Not just the rich and at times delightfully ragged sound, but the cheerful defiance of convention and discarding of political niceties. Rae’s introductions were gems and I hope some of them survive in the recording. He told the audience that it had been a difficult year for him. “It was tough experiencing two elections in as many months and in both cases the got it woefully wrong” (referring to the Scottish referendum and the recent New Zealand Parliamentary elections). “there are winners and losers in politics and there are many assholes”.

Together they evoked a spirit close to the earlier manifestations of the Liberation Jazz Orchestra. Not just the rich and at times delightfully ragged sound, but the cheerful defiance of convention and discarding of political niceties. Rae’s introductions were gems and I hope some of them survive in the recording. He told the audience that it had been a difficult year for him. “It was tough experiencing two elections in as many months and in both cases the got it woefully wrong” (referring to the Scottish referendum and the recent New Zealand Parliamentary elections). “there are winners and losers in politics and there are many assholes”.  It wouldn’t be the ‘Troubles’ if there wasn’t a distinct nod to some of the worlds trouble spots or to political events that confound us. I have chosen a clip ‘Arab Spring Roll’ (John Rae), a title which speaks for itself. Following the establishment of a compelling ostinato bass line, the musicians build a convincing modal bridge to the freedom which follows. Chaotic freedom is the perfect metaphor for the ‘Arab Spring’ uprising. The last number performed was the ANC National anthem and as it concluded, fists rose in remembrance of the anti-apartheid struggle. It is right that we should celebrate the struggles for equality, but sobering to reflect on how far we have to go. The Troubles keep our feet to the flame, while gifting us the best in musical enjoyment.

It wouldn’t be the ‘Troubles’ if there wasn’t a distinct nod to some of the worlds trouble spots or to political events that confound us. I have chosen a clip ‘Arab Spring Roll’ (John Rae), a title which speaks for itself. Following the establishment of a compelling ostinato bass line, the musicians build a convincing modal bridge to the freedom which follows. Chaotic freedom is the perfect metaphor for the ‘Arab Spring’ uprising. The last number performed was the ANC National anthem and as it concluded, fists rose in remembrance of the anti-apartheid struggle. It is right that we should celebrate the struggles for equality, but sobering to reflect on how far we have to go. The Troubles keep our feet to the flame, while gifting us the best in musical enjoyment.

e

e There is a rawness and a primal quality to it, a strong sense of performance. Who would prefer a recording of an Arkestra or an Art Ensemble of Chicago performance over a live show? This was all jazz and all music decoded, not for the cocktail party. The next day I was watching the 1956 Jean Bach film ‘Great Day in Harlem’ and there was Roy ‘Little Jazz’ Eldridge squealing out high note after high note on his trumpet. Again and again, he pushed out a flurry of wild free multi-phonic sounds. Even in the swing era, this had a great effect.

There is a rawness and a primal quality to it, a strong sense of performance. Who would prefer a recording of an Arkestra or an Art Ensemble of Chicago performance over a live show? This was all jazz and all music decoded, not for the cocktail party. The next day I was watching the 1956 Jean Bach film ‘Great Day in Harlem’ and there was Roy ‘Little Jazz’ Eldridge squealing out high note after high note on his trumpet. Again and again, he pushed out a flurry of wild free multi-phonic sounds. Even in the swing era, this had a great effect.