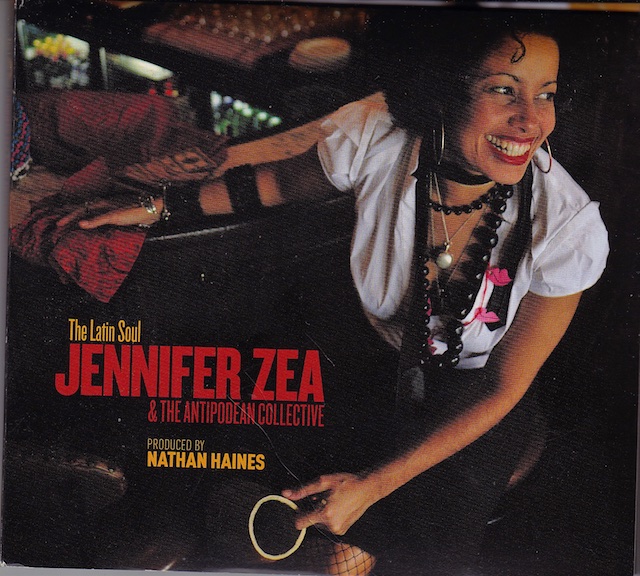

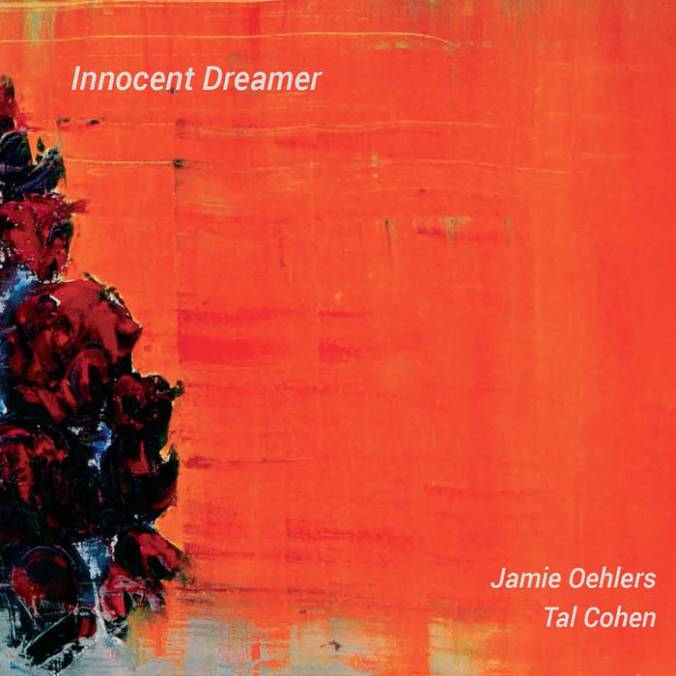

Jamie Oehlers is a tenor saxophone heavyweight who earns widespread respect. His playing is conversational, and like all good conversationalists, he listens as well as he articulates his own point of view. An unashamed melodicist, a musician of subtlety, a dream weaver with a bell-like clarity of tone. Oehlers tours regularly and we are lucky enough to be on his touring circuit. This trip, he was accompanied by Tal Cohen; an Israeli born, New York-based pianist; an artist increasingly coming to the favourable attention of reviewers; an artist praised by fellow musicians. Cohen and Oehlers have been playing together for years and over that time they have built an uncanny rapport. Out of that has emerged something special; their 2016 duo album titled ‘Innocent dreamer’.

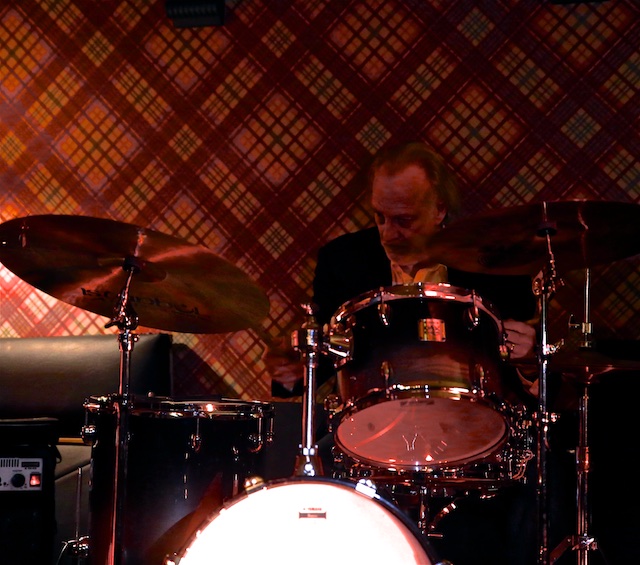

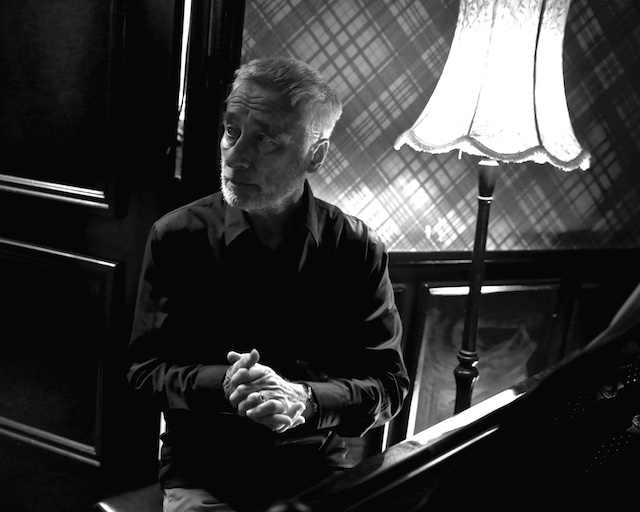

Jamie Oehlers is a tenor saxophone heavyweight who earns widespread respect. His playing is conversational, and like all good conversationalists, he listens as well as he articulates his own point of view. An unashamed melodicist, a musician of subtlety, a dream weaver with a bell-like clarity of tone. Oehlers tours regularly and we are lucky enough to be on his touring circuit. This trip, he was accompanied by Tal Cohen; an Israeli born, New York-based pianist; an artist increasingly coming to the favourable attention of reviewers; an artist praised by fellow musicians. Cohen and Oehlers have been playing together for years and over that time they have built an uncanny rapport. Out of that has emerged something special; their 2016 duo album titled ‘Innocent dreamer’. As far as I know, this was Cohen’s first visit to New Zealand and it was certainly his first visit to the CJC. He’s a compelling pianist and the perfect counter-weight for Oehlers. On duo numbers, they responded to each other as good improvisers should, each giving the other space and expanding the conversation as the explorations deepened. Intimate musical exchanges of this type work best when the musicians care deeply about the project. They work best between friends. We saw two sides to Cohen on this tour. The thoughtful, unhurried, deep improviser and the percussive player who found a groove and worked it to the bone. The second half of the gig brought a rhythm section to the bandstand; Olivier Holland and Ron Samsom. Having such an interesting contrast between sets made both halves work better. The second set was approached with vigour; Oehlers digging into a standard, often preceded by a nice intro, through the head and then… boom. This was when the fireworks happened.

As far as I know, this was Cohen’s first visit to New Zealand and it was certainly his first visit to the CJC. He’s a compelling pianist and the perfect counter-weight for Oehlers. On duo numbers, they responded to each other as good improvisers should, each giving the other space and expanding the conversation as the explorations deepened. Intimate musical exchanges of this type work best when the musicians care deeply about the project. They work best between friends. We saw two sides to Cohen on this tour. The thoughtful, unhurried, deep improviser and the percussive player who found a groove and worked it to the bone. The second half of the gig brought a rhythm section to the bandstand; Olivier Holland and Ron Samsom. Having such an interesting contrast between sets made both halves work better. The second set was approached with vigour; Oehlers digging into a standard, often preceded by a nice intro, through the head and then… boom. This was when the fireworks happened.

The chemistry between Oehlers and Cohen was obvious in the duo set, but adding in the hard-swinging Holland and on-fire Samsom shook up the dynamic once again. Suddenly there were new and wild interactions occurring, short staccato responses, dissonant asides, crazy interjections; these guys were bouncing off each other and above all, they were enjoying themselves. When musicians live in the moment, and the audience feels that magic, they feed it back. The virtuous loop that sustains all performance art. I spoke to Cohen later and talked about playing styles. He is not impressed by pianists who strive to sound like the past. You can respect the past, bring it to your fingertips but still sound like your taking it somewhere new. He did. This night was the proof of the pudding; the standards performed were all living breathing entities. The first set opened with a heartfelt ‘Body & Soul’ (Green) which set the tone. The tune that really took my attention though was Oehlers ‘Armistice’. A beautiful piece conjuring up powerful images and telling its story unequivocally. There was also a nice tune referencing Cohens family. The first set finished with the lively Ellington tribute – ‘Take the Coltrane’ . The second set (the quartet) opened with the lovely ‘It could happen to You’ (Van Heusen), followed by a tune that Oehlers has made his own; ‘On a Clear Day’ (Learner/Lane) – (a recent Oehlers album title). Next, the quartet performed ‘Nardis’ (Evans/Davis) – this was wonderful and it reminded me of the endless re-evaluation and probing of that tune by Evans in his final years. This version did not sound like Evans – it was born again – if any modal tune deserves to live forever, it is surely this one.

The first set opened with a heartfelt ‘Body & Soul’ (Green) which set the tone. The tune that really took my attention though was Oehlers ‘Armistice’. A beautiful piece conjuring up powerful images and telling its story unequivocally. There was also a nice tune referencing Cohens family. The first set finished with the lively Ellington tribute – ‘Take the Coltrane’ . The second set (the quartet) opened with the lovely ‘It could happen to You’ (Van Heusen), followed by a tune that Oehlers has made his own; ‘On a Clear Day’ (Learner/Lane) – (a recent Oehlers album title). Next, the quartet performed ‘Nardis’ (Evans/Davis) – this was wonderful and it reminded me of the endless re-evaluation and probing of that tune by Evans in his final years. This version did not sound like Evans – it was born again – if any modal tune deserves to live forever, it is surely this one.

Lastly, and in keeping with their tradition, Oehlers invited tenor player Roger Manins to the stand. After a quick discussion, they settled on ‘I remember April’ (de Paul). Back and forth they went, weaving arpeggios in and out of each other’s lines – moving like dancers; counterpoint, trading fours, all of the band responding to the challenge and reacting in turns. A KC set piece at the bottom of the Pacific.

Jamie Oehlers (tenor saxophone), Tal Cohen (piano), plus Olivier Holland (bass) and Ron Samsom (drums) – for the CJC Creative Jazz Club, Thirsty Dog, K’Rd Auckland, 27 September 2017. Google Jamie Oehlers Bandcamp.com for a copy of the album.

During the apartheid era in South Africa, a heady brew of danceable Jazz bubbled up from the townships. The all white National Party hated it and a game of ‘whack-a-mole’ followed. As soon as one venue was shut down by the police, another would spring up. The music was resilient and hopeful. No racist or repressive regime likes Jazz because it has rebellion, hope and joyous defiance in its DNA. The Zimbabwean born Thabani Gapara imbibed South African Jazz from his earliest days, eventually taking up the saxophone, that most anti establishment of instruments. Since then, he has performed in Zimbabwean, South African and New Zealand projects.

During the apartheid era in South Africa, a heady brew of danceable Jazz bubbled up from the townships. The all white National Party hated it and a game of ‘whack-a-mole’ followed. As soon as one venue was shut down by the police, another would spring up. The music was resilient and hopeful. No racist or repressive regime likes Jazz because it has rebellion, hope and joyous defiance in its DNA. The Zimbabwean born Thabani Gapara imbibed South African Jazz from his earliest days, eventually taking up the saxophone, that most anti establishment of instruments. Since then, he has performed in Zimbabwean, South African and New Zealand projects.

The popularity of ‘hardbop’ is enduring but we seldom hear it on the band stand. The probable reason is its very familiarity; if you play this music you will be judged against the source. There is also the evolutionary factor: improvised music strives to outlive its yesterdays. It is even less common for musicians to write new music in that idiom or to create a vibe that calls back the era. Such an enterprise invariably falls to experienced musicians; those with the wisdom to reverence the glories without it being merely slavish. Booth and Walters are especially well suited to that task. They have the chops, charts and the imagination and above all, they make things interesting. If you closed your eyes during this gig, you could easily imagine that you were listening to an undiscovered Blue Note album. It was warm, swinging and accessible.

The popularity of ‘hardbop’ is enduring but we seldom hear it on the band stand. The probable reason is its very familiarity; if you play this music you will be judged against the source. There is also the evolutionary factor: improvised music strives to outlive its yesterdays. It is even less common for musicians to write new music in that idiom or to create a vibe that calls back the era. Such an enterprise invariably falls to experienced musicians; those with the wisdom to reverence the glories without it being merely slavish. Booth and Walters are especially well suited to that task. They have the chops, charts and the imagination and above all, they make things interesting. If you closed your eyes during this gig, you could easily imagine that you were listening to an undiscovered Blue Note album. It was warm, swinging and accessible. Booth and Walters are gifted composers and on Wednesday the pair reinforced their compositional reputations. Some of Booth’s tunes have appeared recently in orchestral charts. Walters’ tunes while heard less often are really memorable (‘as good as it gets’ stuck in my head a long time ago). These guys write and arrange well. Notable among Booth’s compositions were ‘Deblaak’, “A Kings Ransome’ and ‘On track’. From Walters; ‘Begin Again’, ‘Queenstown’ and ‘Wellesley Street Mission’. There was also a lovely version of the Metheney/Scofield ‘No Matter What’ from the ‘I Can See Your House From Here’ album. I have posted Booth’s ‘A Kings Ransom’ as a video clip, as it captures their vibe perfectly. Booth has such a lovely burnished tone – a sound production that no doubt comes with maturity and a lot of hard work.

Booth and Walters are gifted composers and on Wednesday the pair reinforced their compositional reputations. Some of Booth’s tunes have appeared recently in orchestral charts. Walters’ tunes while heard less often are really memorable (‘as good as it gets’ stuck in my head a long time ago). These guys write and arrange well. Notable among Booth’s compositions were ‘Deblaak’, “A Kings Ransome’ and ‘On track’. From Walters; ‘Begin Again’, ‘Queenstown’ and ‘Wellesley Street Mission’. There was also a lovely version of the Metheney/Scofield ‘No Matter What’ from the ‘I Can See Your House From Here’ album. I have posted Booth’s ‘A Kings Ransom’ as a video clip, as it captures their vibe perfectly. Booth has such a lovely burnished tone – a sound production that no doubt comes with maturity and a lot of hard work. The last number was Walters ‘Wellesley Street Mission’ and I would have posted that, but my video battery ran out. This is a clear reference to the appalling homeless problem which blights our towns and cities. The bluesy sadness and the deep compassion just flowed out of Walters’ horn – capturing the issue and touching our innermost beings, challenging our better selves. I may be able to extract a cut of this and post it later – we’ll see!

The last number was Walters ‘Wellesley Street Mission’ and I would have posted that, but my video battery ran out. This is a clear reference to the appalling homeless problem which blights our towns and cities. The bluesy sadness and the deep compassion just flowed out of Walters’ horn – capturing the issue and touching our innermost beings, challenging our better selves. I may be able to extract a cut of this and post it later – we’ll see! Lastly, there was that mysterious dancer, appearing from nowhere, drawing sustenance from the music until the street swallowed her again.

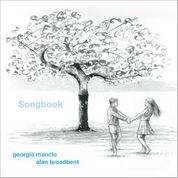

Lastly, there was that mysterious dancer, appearing from nowhere, drawing sustenance from the music until the street swallowed her again.  Since ‘Songbook’ was released three months ago the accolades have come pouring in and it’s no wonder. This is a superb album and destined to remain forever embedded in the Jazz songbook lexicon. The worldwide release was timed to coincide with Broadbent’s seventieth birthday; opening to an enthusiastic audience at Ronnie Scotts; then touring the major clubs and festivals throughout Europe and New York. Much about ‘Songbook’ is classic Broadbent; warm, lyrical, and intimate; not to take anything away from the co-credited Georgia Mancio, a highly acclaimed UK-based vocalist.

Since ‘Songbook’ was released three months ago the accolades have come pouring in and it’s no wonder. This is a superb album and destined to remain forever embedded in the Jazz songbook lexicon. The worldwide release was timed to coincide with Broadbent’s seventieth birthday; opening to an enthusiastic audience at Ronnie Scotts; then touring the major clubs and festivals throughout Europe and New York. Much about ‘Songbook’ is classic Broadbent; warm, lyrical, and intimate; not to take anything away from the co-credited Georgia Mancio, a highly acclaimed UK-based vocalist.  This pairing of voice and harmony, lyrics and melody could hardly be improved upon: it is therefore unsurprising that comparisons are made with the classic songbook era. Here, Broadbent has found the ideal foil for his engaging brand of lyrical Jazz, and as a first, every one of his tunes has accompanying lyrics crafted by Mancio. In Songbook, Broadbent’s Quartet West classic, ‘The Long Goodbye’ has become ‘The Last Goodbye’; a moving reference to the passing of Mancio’s father. Tunes like that have long begged such lyrics and it’s nice to see them penned so beautifully. Back in New Zealand, we watch Broadbent’s ever unfolding story with wonder.

This pairing of voice and harmony, lyrics and melody could hardly be improved upon: it is therefore unsurprising that comparisons are made with the classic songbook era. Here, Broadbent has found the ideal foil for his engaging brand of lyrical Jazz, and as a first, every one of his tunes has accompanying lyrics crafted by Mancio. In Songbook, Broadbent’s Quartet West classic, ‘The Long Goodbye’ has become ‘The Last Goodbye’; a moving reference to the passing of Mancio’s father. Tunes like that have long begged such lyrics and it’s nice to see them penned so beautifully. Back in New Zealand, we watch Broadbent’s ever unfolding story with wonder.  We are proud of him here in his hometown, understanding that his many projects keep him busy; so busy that so we seldom see him these days. As long as we have his albums it is enough, they all have a generous portion of New Zealand buried deep within them. Last month he recorded a new album in the Abbey Road studios, an album with former Woody Herman band mate, drummer Peter Erskine and the amazing bassist Harvie S – plus the London Metropolitan Orchestra. These arrangements could only be Broadbent’s – lush and achingly beautiful. Could there be more Grammy’s on the way?

We are proud of him here in his hometown, understanding that his many projects keep him busy; so busy that so we seldom see him these days. As long as we have his albums it is enough, they all have a generous portion of New Zealand buried deep within them. Last month he recorded a new album in the Abbey Road studios, an album with former Woody Herman band mate, drummer Peter Erskine and the amazing bassist Harvie S – plus the London Metropolitan Orchestra. These arrangements could only be Broadbent’s – lush and achingly beautiful. Could there be more Grammy’s on the way?

During the first half of 2017, a significant number of respected international artists and established local artists appeared at the CJC Creative Jazz Club. While everyone enjoys such a cornucopia of riches, it is also important to keep sight of emerging artists, those who are just below the radar. No local venue manages to showcase the rich diversity of improvising talent as well as the CJC. This is no accident, as there is a guiding philosophy behind the programming of gigs. No artist, however good, gets an ongoing residency; the gigs, therefore, are different every week, are identifiable projects, and this keeps the audiences engaged. An important part of this is showcasing emerging artists.

During the first half of 2017, a significant number of respected international artists and established local artists appeared at the CJC Creative Jazz Club. While everyone enjoys such a cornucopia of riches, it is also important to keep sight of emerging artists, those who are just below the radar. No local venue manages to showcase the rich diversity of improvising talent as well as the CJC. This is no accident, as there is a guiding philosophy behind the programming of gigs. No artist, however good, gets an ongoing residency; the gigs, therefore, are different every week, are identifiable projects, and this keeps the audiences engaged. An important part of this is showcasing emerging artists.

The first number was ‘Tulle’ from the Scofield album, after that we heard a number of his own compositions interspersed with standards. His ‘Who is Kenneth Meyers?’ appealed as did an angular rendition of ‘Surrey with the Fringe on Top (Hammerstein). Given the project in hand, it was unsurprising that he included ‘Boplicity’ by Miles Davis; ‘Birth of The Cool’ being the springboard from which all such arranging sprang. In the second half we heard trumpeter Mike Booth’s ‘Major Event’ – Booth is a skilled arranger and an experienced ensemble composer. It is possible that he has also influenced Swindells’ direction.

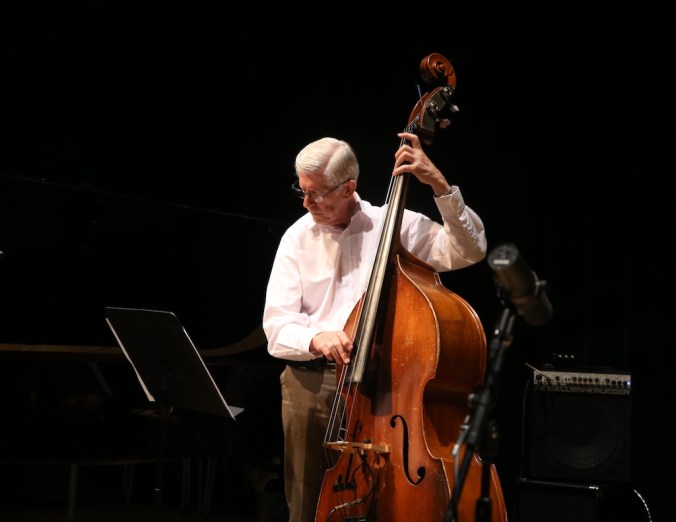

The first number was ‘Tulle’ from the Scofield album, after that we heard a number of his own compositions interspersed with standards. His ‘Who is Kenneth Meyers?’ appealed as did an angular rendition of ‘Surrey with the Fringe on Top (Hammerstein). Given the project in hand, it was unsurprising that he included ‘Boplicity’ by Miles Davis; ‘Birth of The Cool’ being the springboard from which all such arranging sprang. In the second half we heard trumpeter Mike Booth’s ‘Major Event’ – Booth is a skilled arranger and an experienced ensemble composer. It is possible that he has also influenced Swindells’ direction.  There have been two bass-player led groups at the CJC in as many months and both have been excellent. Last weeks featured group was a trio led by Rubim de Toledo: a Canadian from Alberta, of Brazilian origin and a well-established musician. Like many modern improvisers, his influences are diverse; that said his music fits squarely into the Jazz mainstream. The first thing to grab me was his big rounded tone, gifting the tunes with a richness and beauty that captivated from start to finish. While most bass sits deep within the mix, de Toledo’s voice spoke clearly; not by overcrowding his band-mates nor by punching through the others as an electric bassist might, but because every musical utterance sounded right. His melodicism and clarity of ideas were enhanced by devices which I found appealing; his occasional and appropriate use of vibrato at the end of a line, sometimes, rarely, he combined this with a slight bending of the note. He is definitely a successor to the Evans trio model; a bassist who communicates as an equal.

There have been two bass-player led groups at the CJC in as many months and both have been excellent. Last weeks featured group was a trio led by Rubim de Toledo: a Canadian from Alberta, of Brazilian origin and a well-established musician. Like many modern improvisers, his influences are diverse; that said his music fits squarely into the Jazz mainstream. The first thing to grab me was his big rounded tone, gifting the tunes with a richness and beauty that captivated from start to finish. While most bass sits deep within the mix, de Toledo’s voice spoke clearly; not by overcrowding his band-mates nor by punching through the others as an electric bassist might, but because every musical utterance sounded right. His melodicism and clarity of ideas were enhanced by devices which I found appealing; his occasional and appropriate use of vibrato at the end of a line, sometimes, rarely, he combined this with a slight bending of the note. He is definitely a successor to the Evans trio model; a bassist who communicates as an equal. In a live setting and with unfamiliar sidemen, the best plan is to loosen the reigns. This he did and with Kevin Field on Rhodes and fellow Canadian and long time friend Ron Samsom on drums the gig gelled. Much of the gig showcased his compositions, some from his 2014 album ‘The Bridge”. The three standards he played were a killing version of Maiden Voyage (Herbie Hancock), Work Song (Nat Adderly) and a rendering of ‘Recordeme’ (Joe Henderson). His own compositions ranged from the thoughtful ‘Autumn Celeste’ to evocative panoramic tunes like ‘The Gap’ (about the Rockies) and ‘Red Eye’ (about a Brazilian train known locally as the train of death). The gig was a pleasure from start to finish and the enthusiastic audience response said it all.

In a live setting and with unfamiliar sidemen, the best plan is to loosen the reigns. This he did and with Kevin Field on Rhodes and fellow Canadian and long time friend Ron Samsom on drums the gig gelled. Much of the gig showcased his compositions, some from his 2014 album ‘The Bridge”. The three standards he played were a killing version of Maiden Voyage (Herbie Hancock), Work Song (Nat Adderly) and a rendering of ‘Recordeme’ (Joe Henderson). His own compositions ranged from the thoughtful ‘Autumn Celeste’ to evocative panoramic tunes like ‘The Gap’ (about the Rockies) and ‘Red Eye’ (about a Brazilian train known locally as the train of death). The gig was a pleasure from start to finish and the enthusiastic audience response said it all. As I was leaving de Toledo handed me a copy of his recent album ‘The Bridge’ and it wasn’t until yesterday that I found time to play it. What a truly beautiful album this is; beautifully crafted arrangements and tunes which burn with a quiet intensity at any tempo. On ‘The Bridge’, he is surrounded by an ensemble of talented Albertans and a guest artist from the USA. The lineup of bass, trumpet, saxophone, trombone, keyboards, drums (and on track 8 a vocal) is well conceived – balancing airiness with textural richness. The musicianship throughout is noteworthy; particularly Sean Jones on trumpet, a well respected musician from the USA: the keyboardist and everyone making this album memorable. As you would expect with an ensemble and with an album as skillfully recorded as this, de Toledo is less dominant. Here he lets his charts tell the story and they certainly do.

As I was leaving de Toledo handed me a copy of his recent album ‘The Bridge’ and it wasn’t until yesterday that I found time to play it. What a truly beautiful album this is; beautifully crafted arrangements and tunes which burn with a quiet intensity at any tempo. On ‘The Bridge’, he is surrounded by an ensemble of talented Albertans and a guest artist from the USA. The lineup of bass, trumpet, saxophone, trombone, keyboards, drums (and on track 8 a vocal) is well conceived – balancing airiness with textural richness. The musicianship throughout is noteworthy; particularly Sean Jones on trumpet, a well respected musician from the USA: the keyboardist and everyone making this album memorable. As you would expect with an ensemble and with an album as skillfully recorded as this, de Toledo is less dominant. Here he lets his charts tell the story and they certainly do.

In spite of his relative youth, Stephen Thomas is counted as one of New Zealand's better Jazz drummers. He approaches his craft with care and intelligence and it shows in his playing. While his technical skills are superb, he can also communicate on a human level and this is important as it speaks of character. Thomas is a regular on the scene, but like many sidemen and most drummers, he prefers to remain in the shadows. On Wednesday he changed that focus and convincingly staked his claim as band leader.

In spite of his relative youth, Stephen Thomas is counted as one of New Zealand's better Jazz drummers. He approaches his craft with care and intelligence and it shows in his playing. While his technical skills are superb, he can also communicate on a human level and this is important as it speaks of character. Thomas is a regular on the scene, but like many sidemen and most drummers, he prefers to remain in the shadows. On Wednesday he changed that focus and convincingly staked his claim as band leader. The ingredients that contribute to a successful gig are often intangible, but this gig ticked a number of those boxes. While tailored to suit a Jazz audience, it did so without being remote or elitist. Another reason the gig worked was because Thomas used humour to good effect; not just his on stage banter but in the music as well. In a live setting this is important – interacting with the listeners on some level, bringing them inside the circle.

The ingredients that contribute to a successful gig are often intangible, but this gig ticked a number of those boxes. While tailored to suit a Jazz audience, it did so without being remote or elitist. Another reason the gig worked was because Thomas used humour to good effect; not just his on stage banter but in the music as well. In a live setting this is important – interacting with the listeners on some level, bringing them inside the circle. Thomas has an abiding interest in the Ellington/Mingus/Roach, 'Money Jungle' recording and Wednesday provided him with a further opportunity to explore that project. While unusual as a source of standards material, it is a great album to focus on – the perfect vehicle for deconstruction. At the time it was recorded, it stood out for a number of reasons. In fact it shouldn't have worked at all, as the trio members reputedly disliked each other. Each had marked stylistic differences and Ellington was of an earlier generation. Ellington told the others that what they would play on the record should be a collective decision; then he turned up with a set list of his own tunes. The one tune which was not Ellington's was by Juan Tizol – a man who Mingus had once been in a knife fight with and because of whom, he was sacked by Ellington. What should have been a disaster for many reasons was a success. A brave post-bop recording by artists firmly rooted in other eras.

Thomas has an abiding interest in the Ellington/Mingus/Roach, 'Money Jungle' recording and Wednesday provided him with a further opportunity to explore that project. While unusual as a source of standards material, it is a great album to focus on – the perfect vehicle for deconstruction. At the time it was recorded, it stood out for a number of reasons. In fact it shouldn't have worked at all, as the trio members reputedly disliked each other. Each had marked stylistic differences and Ellington was of an earlier generation. Ellington told the others that what they would play on the record should be a collective decision; then he turned up with a set list of his own tunes. The one tune which was not Ellington's was by Juan Tizol – a man who Mingus had once been in a knife fight with and because of whom, he was sacked by Ellington. What should have been a disaster for many reasons was a success. A brave post-bop recording by artists firmly rooted in other eras.

Dennison is a first class musician and someone we don’t hear nearly enough of on the Jazz circuit. He rarely gets to the CJC but when he does it is always a treat. These days he is mostly found doing session work or backing visiting artists and it is hardly surprising that he is a bass player of choice. Whether on upright bass or electric bass he is equally proficient; always an engaging presence, always demonstrating a deep musicality. He has one more string to his bow which can’t be overlooked and that is composition. His tunes are often whimsical, but whatever the mood, a deftly crafted structure sits beneath every phrase. Never over done, bass driven and just right. There is also a thread of melancholia and wistfulness in his ballad writing: these are difficult emotions to evoke and anyone with knowledge of poetry will know, that only the most skilful poets do the moods justice. Dennison can.

Dennison is a first class musician and someone we don’t hear nearly enough of on the Jazz circuit. He rarely gets to the CJC but when he does it is always a treat. These days he is mostly found doing session work or backing visiting artists and it is hardly surprising that he is a bass player of choice. Whether on upright bass or electric bass he is equally proficient; always an engaging presence, always demonstrating a deep musicality. He has one more string to his bow which can’t be overlooked and that is composition. His tunes are often whimsical, but whatever the mood, a deftly crafted structure sits beneath every phrase. Never over done, bass driven and just right. There is also a thread of melancholia and wistfulness in his ballad writing: these are difficult emotions to evoke and anyone with knowledge of poetry will know, that only the most skilful poets do the moods justice. Dennison can. Passels playing was another high point of the evening for me. He just gets better every time we hear him. He is also exactly the right person to interpret mood. I liked the way he approached the tunes, working his way inside them methodically. Sometimes angular, at other times teasing at the melody. During the ballads, he often began with sparse phrasing, establishing mood without overstatement; then, slowly telling his story as if looking at the theme from differing viewpoints. Although he plays decisively, he carefully modulates; generally without flourish or vibrato – pushing at a note until subtle multiphonic textures form – his paper-thin Konitz-like tone saying more than any honk. His versatility is also an asset. Any player who can comfortably move outside and inside while still maintaining a theme is a person worth listening to.

Passels playing was another high point of the evening for me. He just gets better every time we hear him. He is also exactly the right person to interpret mood. I liked the way he approached the tunes, working his way inside them methodically. Sometimes angular, at other times teasing at the melody. During the ballads, he often began with sparse phrasing, establishing mood without overstatement; then, slowly telling his story as if looking at the theme from differing viewpoints. Although he plays decisively, he carefully modulates; generally without flourish or vibrato – pushing at a note until subtle multiphonic textures form – his paper-thin Konitz-like tone saying more than any honk. His versatility is also an asset. Any player who can comfortably move outside and inside while still maintaining a theme is a person worth listening to. McAneny, who initially faced a cable problem, overcame it quickly and delivered a fine performance. Having a Rhodes and a guitar together can be problematical, but the charts and McAneny’s nimbleness enabled him to avoid crowding the space. Howell gave a nice performance and his lines are terrific; He knows what he’s doing but I’d like to hear him bite into his solos a bit more. Drummer Adam Tobeck was on solid ground with this group, he obviously enjoyed the company and reacted well to whatever was thrown his way. After not playing here for a few years, he is now a regular on the bandstand. I like his drum work very much.

McAneny, who initially faced a cable problem, overcame it quickly and delivered a fine performance. Having a Rhodes and a guitar together can be problematical, but the charts and McAneny’s nimbleness enabled him to avoid crowding the space. Howell gave a nice performance and his lines are terrific; He knows what he’s doing but I’d like to hear him bite into his solos a bit more. Drummer Adam Tobeck was on solid ground with this group, he obviously enjoyed the company and reacted well to whatever was thrown his way. After not playing here for a few years, he is now a regular on the bandstand. I like his drum work very much. The last time Nick Granville played in Auckland was 2014. A year prior to that he released his Rattle Jazz album ‘Refractions’ here At that time the CJC was located in an old downtown basement venue and that feels like a lifetime ago. Wellington is his home base and Wellington keeps Granville busy. He teaches, he gigs about town, he backs visiting artists, he plays in shows, he records, he tours and he is the featured guitarist in the Rodger Fox Big Band. The last time I saw him play was in Wellington, but that was a few years ago. Much water has passed under the bridge since then and his reputation has meantime grown apace. I have also kept an eye on his teaching clips, and his ongoing evolution as a musician is evident in these. Almost everything Granville plays is coloured by the blues in some way; that is his thing. On a mid-winter night, it is my thing as well.

The last time Nick Granville played in Auckland was 2014. A year prior to that he released his Rattle Jazz album ‘Refractions’ here At that time the CJC was located in an old downtown basement venue and that feels like a lifetime ago. Wellington is his home base and Wellington keeps Granville busy. He teaches, he gigs about town, he backs visiting artists, he plays in shows, he records, he tours and he is the featured guitarist in the Rodger Fox Big Band. The last time I saw him play was in Wellington, but that was a few years ago. Much water has passed under the bridge since then and his reputation has meantime grown apace. I have also kept an eye on his teaching clips, and his ongoing evolution as a musician is evident in these. Almost everything Granville plays is coloured by the blues in some way; that is his thing. On a mid-winter night, it is my thing as well. With the exception of ‘Alone Together’ by Schwartz/Dietz, all compositions were Grenville’s. Some were from his Rattle Album, such as Tossed Salad & Scrambled Eggs or Blues For Les, while others were much newer. The compositions were all ear-grabbing and most appeared to reference geographical locations or old TV programs. ‘Funky New Orleans Groove Thing’ was certainly true to label; a rhythm-driven groove piece that generated white heat. With Stephen Thomas on the job, the New Orleans beat never sounded better. Thomas is an exceptional drummer.

With the exception of ‘Alone Together’ by Schwartz/Dietz, all compositions were Grenville’s. Some were from his Rattle Album, such as Tossed Salad & Scrambled Eggs or Blues For Les, while others were much newer. The compositions were all ear-grabbing and most appeared to reference geographical locations or old TV programs. ‘Funky New Orleans Groove Thing’ was certainly true to label; a rhythm-driven groove piece that generated white heat. With Stephen Thomas on the job, the New Orleans beat never sounded better. Thomas is an exceptional drummer. A tune that I have heard Granville play previously is ‘Somewhere You’ve Been’. The title is a clever play on Wayne Shorter’s ‘Footprints’. The tune, although not a contrafact of Footprints is close enough to bring it to mind, It is nicely constructed and a good vehicle for a band to play off. For this gig Granville had wisely engaged old friends; Roger Manins, Oli Holland and Steven Thomas. Together on the bandstand, they represented genuine firepower and everyone dug deep when it came to delivering solos

A tune that I have heard Granville play previously is ‘Somewhere You’ve Been’. The title is a clever play on Wayne Shorter’s ‘Footprints’. The tune, although not a contrafact of Footprints is close enough to bring it to mind, It is nicely constructed and a good vehicle for a band to play off. For this gig Granville had wisely engaged old friends; Roger Manins, Oli Holland and Steven Thomas. Together on the bandstand, they represented genuine firepower and everyone dug deep when it came to delivering solos Long after the ANZAC commemorations had finished, when The World Masters Games contestants were either celebrating their success or limping toward the nearest A&E, a largely unheralded gig took place at the KMC in Shortland Street. It was fitting, that on a day of remembrance, the faithful old war horses, the standards, were honoured. It is surprisingly rare to see a standards only instrumental gig these days. The event was curated by Kevin Haines and what a treat it was. The definition of what makes a Jazz standard is a moveable feast, but the safest definition is that the tunes are, or were, from the standard repertoire. Most, but not all standards come from the Great American Songbook, e.g. Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Victor Young, Duke Ellington Ira & George Gershwin etc. Many of them, and often the best, from failed musicals. Other Jazz standards come from the pen of gifted composers like Sonny Rollins.

Long after the ANZAC commemorations had finished, when The World Masters Games contestants were either celebrating their success or limping toward the nearest A&E, a largely unheralded gig took place at the KMC in Shortland Street. It was fitting, that on a day of remembrance, the faithful old war horses, the standards, were honoured. It is surprisingly rare to see a standards only instrumental gig these days. The event was curated by Kevin Haines and what a treat it was. The definition of what makes a Jazz standard is a moveable feast, but the safest definition is that the tunes are, or were, from the standard repertoire. Most, but not all standards come from the Great American Songbook, e.g. Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Victor Young, Duke Ellington Ira & George Gershwin etc. Many of them, and often the best, from failed musicals. Other Jazz standards come from the pen of gifted composers like Sonny Rollins. When introducing the band, Haines stated,” The ability to play the standards well, is the benchmark against which Jazz musicians are ultimately judged”. Assembled on the bandstand were some of New Zealand’s finest musicians. Kevin Haines (bass), Nathan Haines (tenor & soprano saxophones, vocal), Kevin Field (piano), Dixon Nacey (guitar), Ron Samsom (drums). The band gave it everything and the exchanges were beautiful – Nacey and Field conjuring up the Evans/Hall duos, Nathan Haines making his tenor sound like the Desmond Alto. The night was well attended and it will certainly be remembered.

When introducing the band, Haines stated,” The ability to play the standards well, is the benchmark against which Jazz musicians are ultimately judged”. Assembled on the bandstand were some of New Zealand’s finest musicians. Kevin Haines (bass), Nathan Haines (tenor & soprano saxophones, vocal), Kevin Field (piano), Dixon Nacey (guitar), Ron Samsom (drums). The band gave it everything and the exchanges were beautiful – Nacey and Field conjuring up the Evans/Hall duos, Nathan Haines making his tenor sound like the Desmond Alto. The night was well attended and it will certainly be remembered.

There is never a guarantee that two good acts blended into one will work. This one did. DOG and the various iterations of the Peter Koopman trio are each in their way self-contained; exuding a confidence born out of time spent with familiar musicians. Bands that play together over long periods anticipate and react instinctively. Stepping outside of that circle can be a risk, but that is a large part of what improvised music is about. DOG are a tight unit with quick-fire lines and nimble moves. By adding a guitar, DOG risked crowding their musical space; with Koopman, this did not happen. He is an aware and thoughtful musician. The pairing aided by some well-written charts, a pinch of crazy and good humour. The result was a looser sound, but the joy and respect provided all the glue it needed for the gig to work well.

There is never a guarantee that two good acts blended into one will work. This one did. DOG and the various iterations of the Peter Koopman trio are each in their way self-contained; exuding a confidence born out of time spent with familiar musicians. Bands that play together over long periods anticipate and react instinctively. Stepping outside of that circle can be a risk, but that is a large part of what improvised music is about. DOG are a tight unit with quick-fire lines and nimble moves. By adding a guitar, DOG risked crowding their musical space; with Koopman, this did not happen. He is an aware and thoughtful musician. The pairing aided by some well-written charts, a pinch of crazy and good humour. The result was a looser sound, but the joy and respect provided all the glue it needed for the gig to work well. The unison lines and exchanges between guitar, tenor saxophone and Rhodes were just lovely. Kevin Field is always on form and the Rhodes with its chiming clarity was the perfect foil for Koopman and Manins. Field is the complete musician, tasteful, original and with impeccable time feel; Koopman’s guitar benefitting from the well-voiced chords, gently and sparsely comping beneath. Manins also gave a nice solo, and as we have come to expect, he reached for a place beyond the known world. Olivier Holland had a slightly different approach to Koopman’s regular bassist Alduca. Both approaches worked well on Judas Boogie. The interplay between Holland and Samsom was also instructive. As is often the case with good Jazz; the complicated was made to sound easy.

The unison lines and exchanges between guitar, tenor saxophone and Rhodes were just lovely. Kevin Field is always on form and the Rhodes with its chiming clarity was the perfect foil for Koopman and Manins. Field is the complete musician, tasteful, original and with impeccable time feel; Koopman’s guitar benefitting from the well-voiced chords, gently and sparsely comping beneath. Manins also gave a nice solo, and as we have come to expect, he reached for a place beyond the known world. Olivier Holland had a slightly different approach to Koopman’s regular bassist Alduca. Both approaches worked well on Judas Boogie. The interplay between Holland and Samsom was also instructive. As is often the case with good Jazz; the complicated was made to sound easy.

Guitarist Peter Koopman has long been established on the Australian Jazz scene. He returns once or twice a year and when he does he brings interesting projects with him. This tour was no exception; with new compositions, some refocused standards, and a re-jigged trio lineup he hit the mark. Some musicians reach a permanent plateau, and then make only incremental advances from there on. To date, Koopman has been on a steady upwards trajectory; and with little sign of slowing. It’s noticeable in the detail, but also in the overall impression. He is matter of fact on the bandstand, there’s even a hint of diffidence about him, but this only reinforces the impression that he is all about the music. From the first few notes, band and audience are subsumed in the performance.

Guitarist Peter Koopman has long been established on the Australian Jazz scene. He returns once or twice a year and when he does he brings interesting projects with him. This tour was no exception; with new compositions, some refocused standards, and a re-jigged trio lineup he hit the mark. Some musicians reach a permanent plateau, and then make only incremental advances from there on. To date, Koopman has been on a steady upwards trajectory; and with little sign of slowing. It’s noticeable in the detail, but also in the overall impression. He is matter of fact on the bandstand, there’s even a hint of diffidence about him, but this only reinforces the impression that he is all about the music. From the first few notes, band and audience are subsumed in the performance.  One of the subtleties that I noticed between visits is in his tone. It is cleaner but broader, conveying more information, allowing listeners to hear nuance and micro changes in modulation. And on some numbers gentle harmonics, rising off the upper end of a rapid run. His newer compositions also enhanced the project; nicely paced, making room for the whole trio and very appealing to the ear. I was not alone in observing this trajectory. One of our best New Zealand guitarists was later heard to mutter, only half-jokingly, “Damn, I’m off home to burn my guitar”. Australia has a number of excellent guitarists and some are equal to the best in the world. The challenges and opportunities of working in such an environment, have obviously suited Koopman.

One of the subtleties that I noticed between visits is in his tone. It is cleaner but broader, conveying more information, allowing listeners to hear nuance and micro changes in modulation. And on some numbers gentle harmonics, rising off the upper end of a rapid run. His newer compositions also enhanced the project; nicely paced, making room for the whole trio and very appealing to the ear. I was not alone in observing this trajectory. One of our best New Zealand guitarists was later heard to mutter, only half-jokingly, “Damn, I’m off home to burn my guitar”. Australia has a number of excellent guitarists and some are equal to the best in the world. The challenges and opportunities of working in such an environment, have obviously suited Koopman. Judas Boogie, Meth Blue, Dog Annoyance, and Hypochondria were Koopman’s tunes. The band also played a sizzling version of ‘Airegin’ (Sonny Rollins). ‘Airegin’ (Nigeria spelled backward) is a relentlessly upbeat tune and often tackled by guitarists – at least those brave enough. Another Rollins tune was ‘Paradox’. The others ranged from the familiar ‘The best things in life are free’ (De Silva), and ‘The things we did last summer’ (Styne/Cahn) – to the less familiar – ‘The big push’ (by Shorter from his little known ‘Soothsayer’ album) and ‘Montara’ by Bobby Hutcherson (from his amazing latin album of the same name). Why we do not hear more Hutcherson is quite beyond me (thanks for this one PJK).

Judas Boogie, Meth Blue, Dog Annoyance, and Hypochondria were Koopman’s tunes. The band also played a sizzling version of ‘Airegin’ (Sonny Rollins). ‘Airegin’ (Nigeria spelled backward) is a relentlessly upbeat tune and often tackled by guitarists – at least those brave enough. Another Rollins tune was ‘Paradox’. The others ranged from the familiar ‘The best things in life are free’ (De Silva), and ‘The things we did last summer’ (Styne/Cahn) – to the less familiar – ‘The big push’ (by Shorter from his little known ‘Soothsayer’ album) and ‘Montara’ by Bobby Hutcherson (from his amazing latin album of the same name). Why we do not hear more Hutcherson is quite beyond me (thanks for this one PJK).

Australia produces some distinctive, muscular tenor players and Andy Sugg is an example of that phenomena. The first thing that grabs a listener is an awareness of the raw power that fills a room when he blows. I am not just referring to volume or his fat rounded sound, but to the way he communicates an innate sense of musical purpose. This comes across as something beyond mere confidence. Deftly progressing through each tune; no over thinking, just a flow of connected ideas – and all carried on that delicious sound.

Australia produces some distinctive, muscular tenor players and Andy Sugg is an example of that phenomena. The first thing that grabs a listener is an awareness of the raw power that fills a room when he blows. I am not just referring to volume or his fat rounded sound, but to the way he communicates an innate sense of musical purpose. This comes across as something beyond mere confidence. Deftly progressing through each tune; no over thinking, just a flow of connected ideas – and all carried on that delicious sound. It is always tempting to look for comparisons or patterns, it is what listeners do (and probably what many players wish they didn’t do). It is part of how music works, our subconscious looking for a framework, for some reference point – a launching pad, a place of departure where the known departs for the unknown. In Sugg’s playing you could could hear them all. Name a great tenor player and that player was in there, listen harder and suddenly they were gone. Perhaps this is the hall mark of truly innovative players; they channel the essence of others and then dismiss them just as easily.

It is always tempting to look for comparisons or patterns, it is what listeners do (and probably what many players wish they didn’t do). It is part of how music works, our subconscious looking for a framework, for some reference point – a launching pad, a place of departure where the known departs for the unknown. In Sugg’s playing you could could hear them all. Name a great tenor player and that player was in there, listen harder and suddenly they were gone. Perhaps this is the hall mark of truly innovative players; they channel the essence of others and then dismiss them just as easily. One of the joys of improvised music is the eternal conflict between the tangible and the intangible. You hear a phrase or a voicing that is maddeningly familiar, you feel a tingle of anticipation, you are on the verge of naming it – but before it takes form it is gone; dissolved into the intangible. Listening to Sugg is to catch a piece of Brecker, but listening to Sugg is also to hear an original. Tradition and innovation co-existing but ultimately spoken in his own dialect.

One of the joys of improvised music is the eternal conflict between the tangible and the intangible. You hear a phrase or a voicing that is maddeningly familiar, you feel a tingle of anticipation, you are on the verge of naming it – but before it takes form it is gone; dissolved into the intangible. Listening to Sugg is to catch a piece of Brecker, but listening to Sugg is also to hear an original. Tradition and innovation co-existing but ultimately spoken in his own dialect.

Improvised music is a never-ending contest between the familiar and the unexpected. Everything is valid on the journey, but sometimes we forget that tradition can be a springboard and not a straightjacket. We had a good example of that on Wednesday. Because he lives far from here, few if any locals had previously encountered Marc Osterer, but few who heard him will forget his exuberant CJC gig. Born in New York, Osterer has led an interesting musical life. Broadway Shows, New York clubs, principal trumpet (Mexico City Philharmonic) and the Salzburg Festival Austria. While he attended prestigious musical conservatories in New York, there is something else in his sound – something that can’t be learnt purely from academic institutions. Osterer’s Jazz has a firm foothold in the tradition. Louis Armstrong and the great swing-to-bop trumpeters like Sweets Edison. It made perfect sense therefore that the standards he played were from the Songbook and that his own compositions reached deep inside that era.

Improvised music is a never-ending contest between the familiar and the unexpected. Everything is valid on the journey, but sometimes we forget that tradition can be a springboard and not a straightjacket. We had a good example of that on Wednesday. Because he lives far from here, few if any locals had previously encountered Marc Osterer, but few who heard him will forget his exuberant CJC gig. Born in New York, Osterer has led an interesting musical life. Broadway Shows, New York clubs, principal trumpet (Mexico City Philharmonic) and the Salzburg Festival Austria. While he attended prestigious musical conservatories in New York, there is something else in his sound – something that can’t be learnt purely from academic institutions. Osterer’s Jazz has a firm foothold in the tradition. Louis Armstrong and the great swing-to-bop trumpeters like Sweets Edison. It made perfect sense therefore that the standards he played were from the Songbook and that his own compositions reached deep inside that era.

We also witnessed good chemistry between the visiter and his pick up band. It was not the band advertised but what we got was terrific. Matt Steele was flown up from Wellington and locals (fellow UoA Jazz School alumni) Eamon Edmundson-Wells and Tristan Deck completed the rhythm section. Pianist Steele has been gone from Auckland for over a year and is seldom heard here these days. We do hear Edmundson-Wells (bass) and Deck (drums), but to the best of my knowledge, none of them have performed in this context. Absent were the complex time signatures and post bop harmonies. The tunes stayed closer to the melody and the rhythmic requirements were often two-beat or even something closer to second line. As they played through the sets the joy of discovery showed on their faces and we felt it too.

We also witnessed good chemistry between the visiter and his pick up band. It was not the band advertised but what we got was terrific. Matt Steele was flown up from Wellington and locals (fellow UoA Jazz School alumni) Eamon Edmundson-Wells and Tristan Deck completed the rhythm section. Pianist Steele has been gone from Auckland for over a year and is seldom heard here these days. We do hear Edmundson-Wells (bass) and Deck (drums), but to the best of my knowledge, none of them have performed in this context. Absent were the complex time signatures and post bop harmonies. The tunes stayed closer to the melody and the rhythmic requirements were often two-beat or even something closer to second line. As they played through the sets the joy of discovery showed on their faces and we felt it too.  These musicians were still students three years ago but their skills are now well honed. They met the challenge and more. Locals who had not seen Steele play for a while, were buzzing; especially after the blistering Cole Porter standard , ‘It’s alright by me’. Steele’s fleet fingered solo was terrific, and matched by Deck’s bop drumming (complete with appropriately placed bombs and fluid accents). Edmundson-Wells dropped right in behind, pumping out his lines, and it was obvious they were enjoying themselves. Osterer’s compositions tell us how

These musicians were still students three years ago but their skills are now well honed. They met the challenge and more. Locals who had not seen Steele play for a while, were buzzing; especially after the blistering Cole Porter standard , ‘It’s alright by me’. Steele’s fleet fingered solo was terrific, and matched by Deck’s bop drumming (complete with appropriately placed bombs and fluid accents). Edmundson-Wells dropped right in behind, pumping out his lines, and it was obvious they were enjoying themselves. Osterer’s compositions tell us how  comfortable he is with this style of music. His ‘What’s that smell’ (Jazz should be ‘stinky’ he explained) – a New Orleans referencing tune, then ‘Tune for today’ and ‘Bite her back’ based on a Bix Beiderbecke tune. Among the standards was Chet Baker’s version of the little known ‘This is always’, a steamrolling syncopated version of ‘Limehouse Blues’ (Braham) [Note: I have only seen one Kiwi attempt that, Neil Watson on fender] and a version of Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘New Orleans’.

comfortable he is with this style of music. His ‘What’s that smell’ (Jazz should be ‘stinky’ he explained) – a New Orleans referencing tune, then ‘Tune for today’ and ‘Bite her back’ based on a Bix Beiderbecke tune. Among the standards was Chet Baker’s version of the little known ‘This is always’, a steamrolling syncopated version of ‘Limehouse Blues’ (Braham) [Note: I have only seen one Kiwi attempt that, Neil Watson on fender] and a version of Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘New Orleans’. After years traveling the wider Jazz world, Jasmine Lovell-Smith came home; launching her latest album ‘Yellow Red Blue’ at the CJC last Wednesday. The Album features a quintet ‘Towering Poppies’; a group she formed in New York over five years ago. Her New Zealand gig featured locals Roger Manins, Kevin Field, Eamon Edmundson-Wells and Chris O’Connor. After her New York release she garnered a number of favourable reviews and no wonder. This is a lovely album, her compositions and arrangements outstanding, the recording immaculate.

After years traveling the wider Jazz world, Jasmine Lovell-Smith came home; launching her latest album ‘Yellow Red Blue’ at the CJC last Wednesday. The Album features a quintet ‘Towering Poppies’; a group she formed in New York over five years ago. Her New Zealand gig featured locals Roger Manins, Kevin Field, Eamon Edmundson-Wells and Chris O’Connor. After her New York release she garnered a number of favourable reviews and no wonder. This is a lovely album, her compositions and arrangements outstanding, the recording immaculate. Her soprano sound is warm and enveloping, the cleaner tone of her straight horn nicely counterbalancing with the woody earthiness of the bass clarinet, the well constructed charts coming into their own when these delightful interactions occur. The rich textures are never overwhelming, even when strings enter the mix. This is chamber Jazz at it’s best, engaging the listener without resorting to cliché.

Her soprano sound is warm and enveloping, the cleaner tone of her straight horn nicely counterbalancing with the woody earthiness of the bass clarinet, the well constructed charts coming into their own when these delightful interactions occur. The rich textures are never overwhelming, even when strings enter the mix. This is chamber Jazz at it’s best, engaging the listener without resorting to cliché.

As another DOG night approached I could feel the excitement in my bones. I had followed their tracks from the groups inception, enjoying every moment along the trail. I was at their first gig in February 2013 and it amazed me then just how rounded and complete they were. If you search for the ‘(Dr) Dog’ post in this blog site you will find a video from that gig. Man that blew me away. I just couldn’t get the tunes and the excitement of that night out of my head. Later I used a cut ‘Dideldideldei’ (Holland) as the signature for my YouTube site. I also sent the cut to a Jazz DJ friend Eddie B in LA and he played it on his show. Unsurprisingly people phoned in immediately wanting to know, “who were those amazing cats”? Before long the group decided to record – everyone who heard them wanted more. DOG seemed to encapsulate everything that was good and exciting about the local scene – DOG was, and still is, something special.

As another DOG night approached I could feel the excitement in my bones. I had followed their tracks from the groups inception, enjoying every moment along the trail. I was at their first gig in February 2013 and it amazed me then just how rounded and complete they were. If you search for the ‘(Dr) Dog’ post in this blog site you will find a video from that gig. Man that blew me away. I just couldn’t get the tunes and the excitement of that night out of my head. Later I used a cut ‘Dideldideldei’ (Holland) as the signature for my YouTube site. I also sent the cut to a Jazz DJ friend Eddie B in LA and he played it on his show. Unsurprisingly people phoned in immediately wanting to know, “who were those amazing cats”? Before long the group decided to record – everyone who heard them wanted more. DOG seemed to encapsulate everything that was good and exciting about the local scene – DOG was, and still is, something special. There are so many aspects to this group that it is hard enumerate them all; of course there are the outrageous dog jokes, the brilliant compositions from each band member, the powerful stage presence, but it is something else that excites me the most. This is a band that could gig anywhere in the world and we could hold our heads up, knowing that they would do us proud, tell our story. I felt excited when they were nominated for ‘album of the year’ and as pleased as a dog with two tails when they won the ‘Jazz Tui’. Now it is rumoured that a new DOG album is on the way. I can’t wait.

There are so many aspects to this group that it is hard enumerate them all; of course there are the outrageous dog jokes, the brilliant compositions from each band member, the powerful stage presence, but it is something else that excites me the most. This is a band that could gig anywhere in the world and we could hold our heads up, knowing that they would do us proud, tell our story. I felt excited when they were nominated for ‘album of the year’ and as pleased as a dog with two tails when they won the ‘Jazz Tui’. Now it is rumoured that a new DOG album is on the way. I can’t wait. Throughout the sets were a scattering of familiar DOG compositions – plus a few new ones (like ‘Merde’ by Samsom and Hollands ‘Shceibenwischer’). All of the tunes sounded fresh and somehow different, perhaps because Kevin Field was playing a Rhodes and not a piano. I love the Rhodes in all its antique glory and in Field’s hands it is especially wonderful. It cut through the room like crystal. Hearing the familiar tunes like ‘Peter the Magnificent’ (Manins), ‘Icebreaker’ (Field) and ‘Sounds like Orange’ was like meeting old friends. The last track of the evening was the familiar ‘Dideldideldei'(Holland). DOG ripped into it with the usual abandon, leaving us shaking our heads in disbelief and grinning like Cheshire cats.

Throughout the sets were a scattering of familiar DOG compositions – plus a few new ones (like ‘Merde’ by Samsom and Hollands ‘Shceibenwischer’). All of the tunes sounded fresh and somehow different, perhaps because Kevin Field was playing a Rhodes and not a piano. I love the Rhodes in all its antique glory and in Field’s hands it is especially wonderful. It cut through the room like crystal. Hearing the familiar tunes like ‘Peter the Magnificent’ (Manins), ‘Icebreaker’ (Field) and ‘Sounds like Orange’ was like meeting old friends. The last track of the evening was the familiar ‘Dideldideldei'(Holland). DOG ripped into it with the usual abandon, leaving us shaking our heads in disbelief and grinning like Cheshire cats. The Thirsty Dog works well as a venue, having good acoustics, good sight-lines and a sizeable bandstand. They also serve snack food and they are most welcoming. The first DOG album is available at

The Thirsty Dog works well as a venue, having good acoustics, good sight-lines and a sizeable bandstand. They also serve snack food and they are most welcoming. The first DOG album is available at  Against a background of complacency in regard to the ever declining biodiversity on the planet, one band is determined to raise our awareness. Those who have encountered the quartet on prior occasions will know the back story, connect the dots. GRG67 arose out of an impulse of crustacean empathy, an emotion usually confined to marine biologists and not Jazz musicians. However, once you grasp the fact that the band’s founder is Roger Manins, the rest falls into place. A sustainable fisher and co-manager of a small menagerie, Manins could best be described as the David Attenborough of the tenor saxophone. His world is strewn with animals and that’s the way he prefers it.

Against a background of complacency in regard to the ever declining biodiversity on the planet, one band is determined to raise our awareness. Those who have encountered the quartet on prior occasions will know the back story, connect the dots. GRG67 arose out of an impulse of crustacean empathy, an emotion usually confined to marine biologists and not Jazz musicians. However, once you grasp the fact that the band’s founder is Roger Manins, the rest falls into place. A sustainable fisher and co-manager of a small menagerie, Manins could best be described as the David Attenborough of the tenor saxophone. His world is strewn with animals and that’s the way he prefers it.

Each tune title was accompanied by a personal story or zoological insight; each bird was treated with deep respect. With titles like ‘chook empathy’, ‘chook 40’, ‘ginger chook’, ‘dark chook sin’ we were afforded some rare insights into the avian world. ‘Chook 40’ was not about the 40th chook as you might suppose. It opened our eyes to the fact that chooks have one more chromosome than humans. During that particular tune you could really sense that extra chromosome. ‘Dark chook sin’ was an invitation to anthropomorphism. What would a chook sin look like? Manins felt that Mallard ducks were more likely to sin than a chook (anyone living near ducks who has a deck will have a view on this).

Each tune title was accompanied by a personal story or zoological insight; each bird was treated with deep respect. With titles like ‘chook empathy’, ‘chook 40’, ‘ginger chook’, ‘dark chook sin’ we were afforded some rare insights into the avian world. ‘Chook 40’ was not about the 40th chook as you might suppose. It opened our eyes to the fact that chooks have one more chromosome than humans. During that particular tune you could really sense that extra chromosome. ‘Dark chook sin’ was an invitation to anthropomorphism. What would a chook sin look like? Manins felt that Mallard ducks were more likely to sin than a chook (anyone living near ducks who has a deck will have a view on this). The quartet played with wild enthusiasm in both sets and the good humour of the evening was infectious. Given the subject matter it was only fitting that the gig took place at the Thirsty Dog (dogs are also a recurring theme with Manins). The venue was congenial and the acoustics good. What more could you want on the last night of Spring. This band is a rallying cry, reminding us that in this troubled world we shouldn’t take the good things for granted. At a time when we are buffeted by the ill winds of international politics, the arts matter more than ever. New Zealand Jazz rewards us in so many ways and the diversity of improvised music in our city is a treasure. You get good musicianship and fun combined – and if you’re lucky a musical insight into the natural world around us.

The quartet played with wild enthusiasm in both sets and the good humour of the evening was infectious. Given the subject matter it was only fitting that the gig took place at the Thirsty Dog (dogs are also a recurring theme with Manins). The venue was congenial and the acoustics good. What more could you want on the last night of Spring. This band is a rallying cry, reminding us that in this troubled world we shouldn’t take the good things for granted. At a time when we are buffeted by the ill winds of international politics, the arts matter more than ever. New Zealand Jazz rewards us in so many ways and the diversity of improvised music in our city is a treasure. You get good musicianship and fun combined – and if you’re lucky a musical insight into the natural world around us. I have posted the bands signature tune GRG67 as it simply crackled (cackled) with life (and it broke a previous speed record). These guys are fine musicians and GRG67 was never better than on this night. These guys sizzle.

I have posted the bands signature tune GRG67 as it simply crackled (cackled) with life (and it broke a previous speed record). These guys are fine musicians and GRG67 was never better than on this night. These guys sizzle. While not located on the Jazz touring circuit in the way Europe is, New Zealand gets some surprising and unexpected treats throughout the year. This was certainly one of them. Because I’ve been travelling recently, I had not noticed this gig coming up and it caught me quite off guard. From time to time I’ve heard mention of the New Zealand born composer and saxophonist Hayden Chisholm, but I had never heard him play. The little that I did know, was that he’d lived in Europe for many years and that he’d been a microtonal innovator. His CV reveals an amazing diversity of achievements and among them; teaching, composing for large ensembles, recording around the world, film soundtrack scoring, festival directing, touring extensively and collaborating with installation artists. He is obviously not a musician to be pigeonholed easily and my expectations inclined me toward multi-phonic explorations or something akin to the wonderful Bley /Giuffre/Swallow ’61 trio’. What I heard was closer to the equally wonderful Bley (Karla)/Swallow/Shepherd trio.

While not located on the Jazz touring circuit in the way Europe is, New Zealand gets some surprising and unexpected treats throughout the year. This was certainly one of them. Because I’ve been travelling recently, I had not noticed this gig coming up and it caught me quite off guard. From time to time I’ve heard mention of the New Zealand born composer and saxophonist Hayden Chisholm, but I had never heard him play. The little that I did know, was that he’d lived in Europe for many years and that he’d been a microtonal innovator. His CV reveals an amazing diversity of achievements and among them; teaching, composing for large ensembles, recording around the world, film soundtrack scoring, festival directing, touring extensively and collaborating with installation artists. He is obviously not a musician to be pigeonholed easily and my expectations inclined me toward multi-phonic explorations or something akin to the wonderful Bley /Giuffre/Swallow ’61 trio’. What I heard was closer to the equally wonderful Bley (Karla)/Swallow/Shepherd trio. The gig subsumed us in pure unalloyed ballad beauty – beauty of a kind that is exceedingly rare. The programme (with one exception) was of original ballads; pieces composed by either Chisholm or Norman Meehan. Meehan was exactly the right pianist for this gig – a tasteful musician who knows when to lay out, and who never over-ornaments. His sensitivity and minimalist approach creating a bigger implied sound; each note or voicing inviting the audience deeper into an unfolding story. Later when I commented on this he repeated Paul Bley’s advice, “If somebody else sounds good, you’re not needed. So you are like a doctor with a little black bag coming to a record date” (from ‘Time will Tell’ Meehan). Paul Dyne on bass was the ideal foil for Chisholm and Meehan. Again he made each note count without busyness. Because this was an acoustic trio with the piano and saxophone unmiked, the resonance of the bass carried more weight, every harmonic adding a subtle layer. With Meehan playing so sparsely and Chisholm sailing in the clean air above, the subtlties of the soundscape were liberated until the room sang.

The gig subsumed us in pure unalloyed ballad beauty – beauty of a kind that is exceedingly rare. The programme (with one exception) was of original ballads; pieces composed by either Chisholm or Norman Meehan. Meehan was exactly the right pianist for this gig – a tasteful musician who knows when to lay out, and who never over-ornaments. His sensitivity and minimalist approach creating a bigger implied sound; each note or voicing inviting the audience deeper into an unfolding story. Later when I commented on this he repeated Paul Bley’s advice, “If somebody else sounds good, you’re not needed. So you are like a doctor with a little black bag coming to a record date” (from ‘Time will Tell’ Meehan). Paul Dyne on bass was the ideal foil for Chisholm and Meehan. Again he made each note count without busyness. Because this was an acoustic trio with the piano and saxophone unmiked, the resonance of the bass carried more weight, every harmonic adding a subtle layer. With Meehan playing so sparsely and Chisholm sailing in the clean air above, the subtlties of the soundscape were liberated until the room sang. The compositions were varied but all were marvellous. Some so gorgeous as to take the breath away – others possessing edge – all beautifully constructed. The trio worked as an effective unit, but the Chisholm effect was inescapable. The man is simply exceptional, his lines, phrasing and tone jaw dropping. I have no doubt that his technical skills are second to none, but listening to him you never give that a thought. Every musical utterance plunged deep into your soul in the way a Konitz line does. Chisholm is quite original and modern but I fancied that I heard some faint echoes of the great altoists on Wednesday night. Perhaps that was just my imagination, but Lee Konitz (and surprisingly to me), even Art Pepper came mind; especially during Meehan’s wonderfully soulful tune ‘Nick Van Diyk’. I have posted that clip (which is bookended with a lovely Chisholm tune ‘In Day Light Mourning’, where he plays a lament against a drone). The lament references the music of India and Japan, utilising extended technique (Chisholm has studied in both countries).

The compositions were varied but all were marvellous. Some so gorgeous as to take the breath away – others possessing edge – all beautifully constructed. The trio worked as an effective unit, but the Chisholm effect was inescapable. The man is simply exceptional, his lines, phrasing and tone jaw dropping. I have no doubt that his technical skills are second to none, but listening to him you never give that a thought. Every musical utterance plunged deep into your soul in the way a Konitz line does. Chisholm is quite original and modern but I fancied that I heard some faint echoes of the great altoists on Wednesday night. Perhaps that was just my imagination, but Lee Konitz (and surprisingly to me), even Art Pepper came mind; especially during Meehan’s wonderfully soulful tune ‘Nick Van Diyk’. I have posted that clip (which is bookended with a lovely Chisholm tune ‘In Day Light Mourning’, where he plays a lament against a drone). The lament references the music of India and Japan, utilising extended technique (Chisholm has studied in both countries).  It was one of those concerts that made you feel lucky. The sort of concert that you will recall in later years and regale those who missed it with vivid descriptions – enough to make them green with envy. For those who missed the gig or for those who want to relive it, the trio are recording this week. I will keep you posted on that and on where to obtain the album. In addition Norman Meehan has a new book out – a history of New Zealand Jazz. That can be ordered through any main street book outlet (my order is in).

It was one of those concerts that made you feel lucky. The sort of concert that you will recall in later years and regale those who missed it with vivid descriptions – enough to make them green with envy. For those who missed the gig or for those who want to relive it, the trio are recording this week. I will keep you posted on that and on where to obtain the album. In addition Norman Meehan has a new book out – a history of New Zealand Jazz. That can be ordered through any main street book outlet (my order is in). Frank Gibson is a drummer of international repute, a sideman, educator and bandleader. While he is a versatile drummer, his predilection is for bebop and hard-bop (especially Monk). On Wednesday the 16th November, our last night at the Albion for a while, we heard six Monk tunes (plus tunes by Wes Montgomery, Lee Morgan, Joe Henderson and Sam Rivers).

Frank Gibson is a drummer of international repute, a sideman, educator and bandleader. While he is a versatile drummer, his predilection is for bebop and hard-bop (especially Monk). On Wednesday the 16th November, our last night at the Albion for a while, we heard six Monk tunes (plus tunes by Wes Montgomery, Lee Morgan, Joe Henderson and Sam Rivers). This is not a clone of the original Monk bands, but a modern quartet connected to the Monk vibe by musical lineage.

This is not a clone of the original Monk bands, but a modern quartet connected to the Monk vibe by musical lineage. There were familiar, much-loved Monk tunes and a few that are seldom heard such as ‘Light Blue’ and ‘Eronel’. Monk wrote around 70 compositions and they are instantly recognisable as being his. The angularity, quirky twists, the choppy rhythms, the lovely melodies and particular harmonic approach – a heady brew to gladden the heart of a devoted listener. We never tire of him or his interpreters. After Ellington, Monk compositions are the most recorded in Jazz. We remain faithful to his calling whether our tastes run to the avant-garde, swing or are firmly rooted in the mainstream. These tunes are among the essential buttresses holding up modern Jazz. They are open vehicles inviting endless and interesting explorations. They are a soundtrack to the Jazz life.

There were familiar, much-loved Monk tunes and a few that are seldom heard such as ‘Light Blue’ and ‘Eronel’. Monk wrote around 70 compositions and they are instantly recognisable as being his. The angularity, quirky twists, the choppy rhythms, the lovely melodies and particular harmonic approach – a heady brew to gladden the heart of a devoted listener. We never tire of him or his interpreters. After Ellington, Monk compositions are the most recorded in Jazz. We remain faithful to his calling whether our tastes run to the avant-garde, swing or are firmly rooted in the mainstream. These tunes are among the essential buttresses holding up modern Jazz. They are open vehicles inviting endless and interesting explorations. They are a soundtrack to the Jazz life.

Au revoir is more than a simple good-bye. The fuller meaning is ‘until we meet again’. Jazz pianist, broadcaster and educator Phil Broadhurst is about to move to Paris, where he will reside for a few years (along with his partner vocalist/pianist Julie Mason). He assures us that he will return and it is not unreasonable to expect him to arrive back with new compositions and new projects to showcase. A Francophile (and francophone), Broadhurst has long been influenced by the writers and musicians of France. His last three albums ‘The dedication trilogy’ all contain strong references to that country. Wednesdays gig was centred on his recent output, but with new tunes and a surprise or two thrown in.